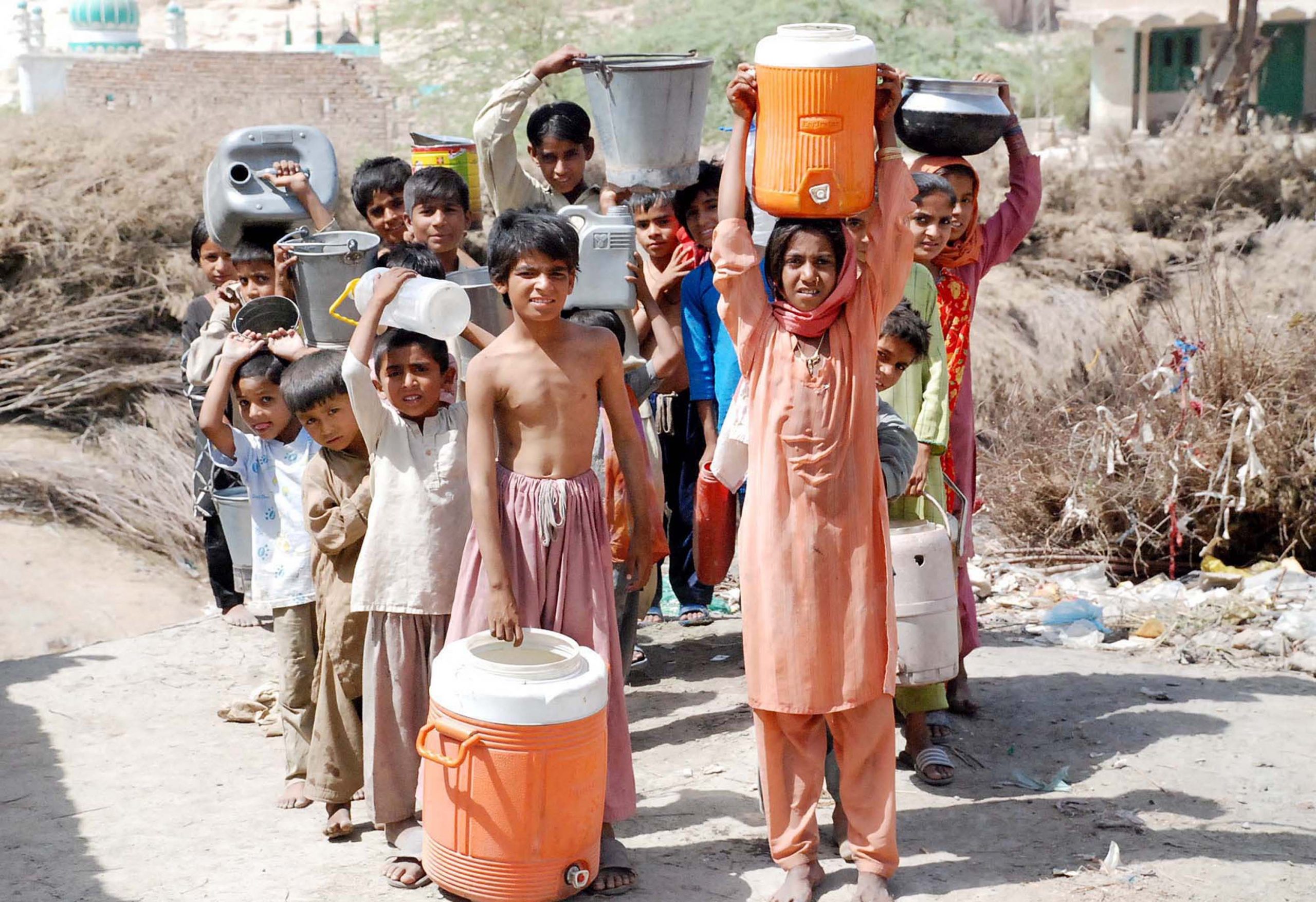

[dropcap font="" size="50px" background="" color="" circle="0" transparent="0"]W[/dropcap]omen and girls in low-income countries across the world still struggle with access to menstrual products, hygiene facilities, and education, putting their physical health at risk.

Menstrual Hygiene Day, observed throughout the world on May 28, highlights this reality and the urgent need to address it. “Every month, 1.8 billion people across the world menstruate. Millions of these girls, women, transgender men and non-binary persons are unable to manage their menstrual cycle in a dignified, healthy way,” says

UNICEF.

Access to menstrual hygiene products — such as reusable pads and disposable pads — is key to improving menstrual health and hygiene. But

a holistic approach is needed, too.

“Menstrual needs are not just pads,” said Pema Lhaki, executive director of the

Nepal Fertility Care Center, in

Devex. “It is medicine if [the menstruator] has problems, water facilities to go privately to a toilet, a disposal facility for pads.”

Devex reports that, like pads, young schoolgirls have become a symbol within menstrual activism. However, this narrow focus means that other menstruators are often left out.

Disabled women like

Tanzila Khan — an award-winning author, public speaker, and rights activist for women with disabilities in Pakistan — menstruate, too. Khan has been unable to use her legs since birth, reports

Deutsche Welle.

One day, she got her period while on the way to a meeting in her home city of Lahore. But Khan was hard-pressed to find a shop with wheelchair access from which she could buy a napkin. The difficulty she experienced in accessing menstrual products inspired her to launch

Girlythings.pk, an app that delivers menstrual, reproductive health, and maternity products to women anonymously.

Women deprived of liberty get their periods, too, and suffer monthly indignity. In the

Philippines, female prisoners in the Correctional Institution for Women in Mandaluyong City lack access to menstrual hygiene products and ample water and toilets. In Thailand, women in Chaiyaphum Prison, north of Bangkok, received only 12 sanitary pads each for the whole year of 2020 — 10 times less than their usual annual quota, reports

Reuters.

Women displaced by conflict go through another kind of hell. Women and girls in Myanmar lack access to sanitary pads, clean water, and privacy, reports

Al Jazeera. In camps that sprawl across Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district,

up to 75 percent of Rohingya adolescents are unable to meet their menstrual hygiene needs, reports the

Pulitzer Center.