|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

he day of her wedding was the start of her terrifying ordeal.

“I was in a lot of pain at my Walima (a Muslim ceremony held after marriage), because of my husband’s forced intimacy,” says the 25-year-old from rural Pakistan who declines to be named. “I told my friends (about it), but they dismissed my anguish, attributing it to my husband’s curiosity to know about my virginity. I had no idea that it was only the beginning.”

The young woman says that since then her husband has often forced her to have non-consensual sex. But with Pakistan’s societal norms dictating that it is her duty to fulfill her husband’s desires, she feels powerless to object. The woman also says, “At least in our area, women endure similar experiences, but it is normal.”

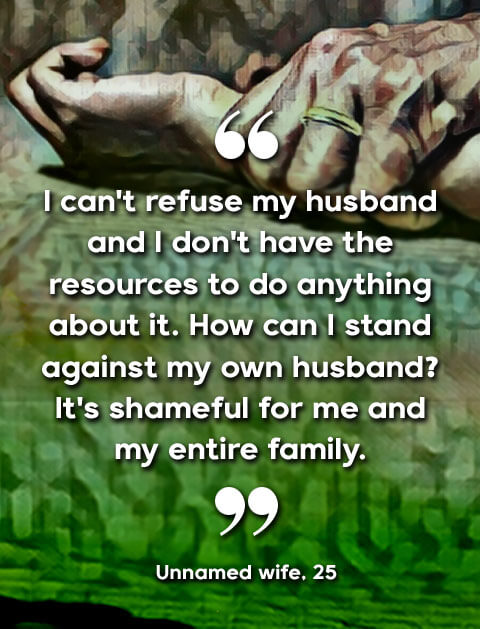

Even when told that a man in Sindh province was recently fined and sentenced to three years in jail for sodomizing his wife, the young wife and mother says that the court decision changes nothing for her. “I can’t refuse my husband,” she says, “and I don’t have the resources to do anything about it. How can I stand against my own husband? It’s shameful for me and my entire family.”

Indeed, while women’s rights advocates and legal experts agree that the Jan. 15 decision of a Sindh court established an important legal precedent that can help protect women from abuse, they concede that women’s rights still have a long way to go in Pakistan, and especially within the context of marriage.

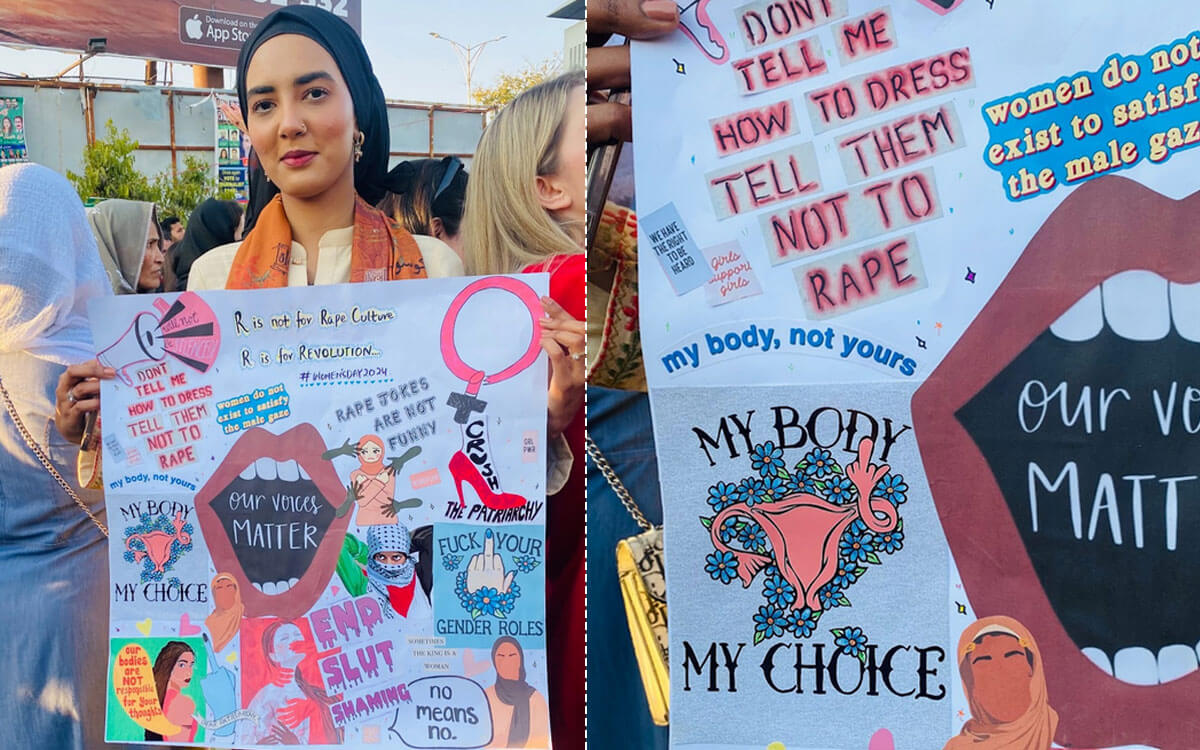

Marital rape in particular is deeply entrenched in the country’s patriarchal structures and societal norms, thus posing a complex and formidable challenge for women’s rights advocates. Even prominent activist organizations such as Aurat March recognize that combating marital rape necessitates not only legal and policy reforms, but also broader societal shifts in attitudes and beliefs surrounding gender and sexuality.

The remarks of a university cleaner in her late 40s in fact underscore how societal attitudes toward marital rape in Pakistan play a significant role in perpetuating the suffering of women in the country who have to endure it.

“In our society, only men can have pleasure, while women are expected to provide it, whether they want to or not,” she says.

She adds that she will never file a complaint and risk her marriage over what she considers “a small matter.”

“It’s not just me, the majority of women here are in the same situation,” the cleaner says. “So, if they are not coming out and saying anything about it, why would I do it? This is how society works. I know that doing this (file a case) will ruin my life, and I will be the one who will suffer.”

Not just a Pakistani problem

Such attitudes are not unique to Pakistan. Even in the United States, where at least 10 percent of married women are estimated to have experienced being raped by their husbands, marital rape is the most under-reported form of sexual assault, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV).

The Texas-based coalition notes, “Many Americans do not believe that marital rape is actually rape.” In an undated document, NCADV says that when it comes to laws in the United States, “even now, some states still have some form of spousal rape exemptions, and it is often legally considered a different, lesser crime than non-spousal rape.”

A 2021 joint report by the rights groups Equality Now and Dignity Alliance International meanwhile said that more than 104 countries worldwide consider marital rape a criminal offense, but in South Asia, only Bhutan and Nepal do so “despite its alarming prevalence.”

In truth, Pakistan’s Anti Rape (Investigation & Trial) Act of 2021 and Criminal Laws (Amendment) Act of 2021 do not cite marital rape as a specific offense. They do, however, allow for the prosecution of rape where the perpetrator is married to the victim.

Shabbir Hussain, a lawyer associated with the AGHS Legal Aid Cell, says that these pieces of legislation are big steps forward in combating marital rape and making abusers accountable.

Hussain explains that while the Pakistan Penal Code’s (PPC) section 375 does not explicitly mention marital rape, it does acknowledge that sexual intercourse within marriage can constitute rape if it occurs without the wife’s consent. Section 376 of the PPC provides punishment for committing rape.

Section 377, which relates to the commission of an unnatural offense, now also falls within the ambit of the expanded definition of rape. Therefore, Hussain says, the process for filing a complaint or seeking legal action in marital rape will follow the same process as provided for the offense of rape.

This signifies a crucial recognition of the principle of consent within marital relationships. The Sindh case apparently centered on the act forced on the wife as being “unnatural.”

Rabia Usman, director of the Human Crisis Centre for Women in Punjab, says that her organization has encountered situations where women had suffered greatly as a result of their husbands’ unnatural physical intimacy, notably anal intercourse. Sodomy not only causes physical pain but also inflicts profound psychological distress on these women.

For most women, the act leaves them feeling degraded and conflicted, especially given their belief that engaging in it is sinful (haram), which adds a layer of spiritual conflict to their ordeal.

Men and family first

Consent dynamics in marital relationships have a significant psychological influence on women, affecting their sense of autonomy, self-worth, and mental health. In countries such as Pakistan, conventional gender roles and cultural expectations usually have a profound impact on marital dynamics and affect women’s relationship satisfaction.

In such societies where family honor has prime importance, women feel obligated to prioritize their partner’s wants and desires over their own, even if this means things are done to them without their consent.

According to the Gender Snapshot 2023 by U.N. Women, across the globe each year, 245 million women and girls aged 15 and above become “victims of physical and/or sexual violence perpetuated by an intimate partner.” In Pakistan, a 2009 study found that 33 percent of married women had experienced marital rape.

Yet up until September 2018, not a single case of marital rape was filed or prosecuted in Pakistan. One reason for this could be the lack of a law addressing marital rape. Another may be the low conviction rate in cases of rape that do not even occur within marriages.

In a 2020-2021 factsheet, the non-profit War Against Rape (WAR) said that more than 22,000 rape cases were filed in Pakistan during a six-year period. By the time the factsheet came out, only 77 (0.3 percent) of the cases had ended in convictions, while just 18 percent had reached prosecution stage.

Aurat March representative Fatima Jan comments that women who experience marital rape “will largely refrain from reporting their husbands given that they feel ashamed and know well that no individual will be held responsible.”

But the biggest deterrents in women filing marital-rape cases seem to be cultural norms and societal views. The idea that marriage is sacred, for instance, is widely held in Pakistan. This notion may take precedence over the recognition of marital rape as a crime, and underplays or even ignores women’s rights in marriage.

“In certain situations, when a woman comes to us with her mother, the mother begins to share her worry, as it has happened to her as well, which has a significant impact on their mental health,” says Usman of the Human Crisis Centre for Women. “But, in the end, they are compelled to return (home) and suffer because they have children and are unable to speak out. Many women are suffering silently.”

Mutual consent in Islam

In predominantly Muslim Pakistan, misinterpretations of Islamic teaching also add to the social pressures on women, who may not want to entertain all the sexual advances of their husbands all the time.

Islamic religious scholar Mufti Maaz Hamdard says that the misinterpretation of Islamic teachings to satisfy one’s personal interests is a widespread problem. But he stresses how Islam values women and how men have a duty to respect and put their wives’ wants and well-being first. He also asserts that cultural prejudices within society frequently obscure the actual teachings of Islam, causing misconceptions.

“It’s our society that is misinterpreting Islam,” he says. “Islam, from the outset, instructs us to ensure mutual consent when getting married. Therefore, if two people marry willingly, then such issues would not arise. Furthermore, Islam grants us the right of divorce if one is not happy or facing issues.”

Maaz adds that most people and religious scholars “will not tell you these things.” Rather, he says, they will misinterpret them, especially in a country like Pakistan where religion is frequently exploited.

Women’s rights advocates and legal organizations, however, are actively working to increase public awareness of the prevalence and outcomes of marital rape by posting educational messages on social media. Aurat March, for example, says that among its activities are efforts that challenge harmful attitudes and beliefs that perpetuate this form of violence against women.

But Jan admits that as a volunteer-led movement, Aurat March faces significant limitations in terms of resources. These constraints include limited time, funding, and manpower, which eventually affect the organization’s ability to address every problem comprehensively.

In the meantime, the university cleaner says that she has yet to say ‘no’ to her husband even during times when she does not want to be intimate with him. She is adamant that a formal complaint is out of the question. “Although I earn money by working here, all my decisions are made by my husband, who holds the power. I have been enduring this for so many times that it now seems normal to me,” she says. ◉

This story received support from The Pleasure Project.