|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

E

lections are supposed to provide opportunities for a country’s people to be heard, but a significant portion of India’s 1.4 billion-strong population fears that the six-week polls that begin this April 19 will end up silencing them some more.

As it is, India’s religious minorities, which make up some 20 percent of the country’s people, already feel that their voices are either deliberately being drowned out or ignored under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In contrast to India’s secularism as enshrined in its constitution, the BJP champions Hindutva, which as the U.K.-based publication The Economist puts it, “equates Indianness with Hinduism.” India is predominantly Hindu.

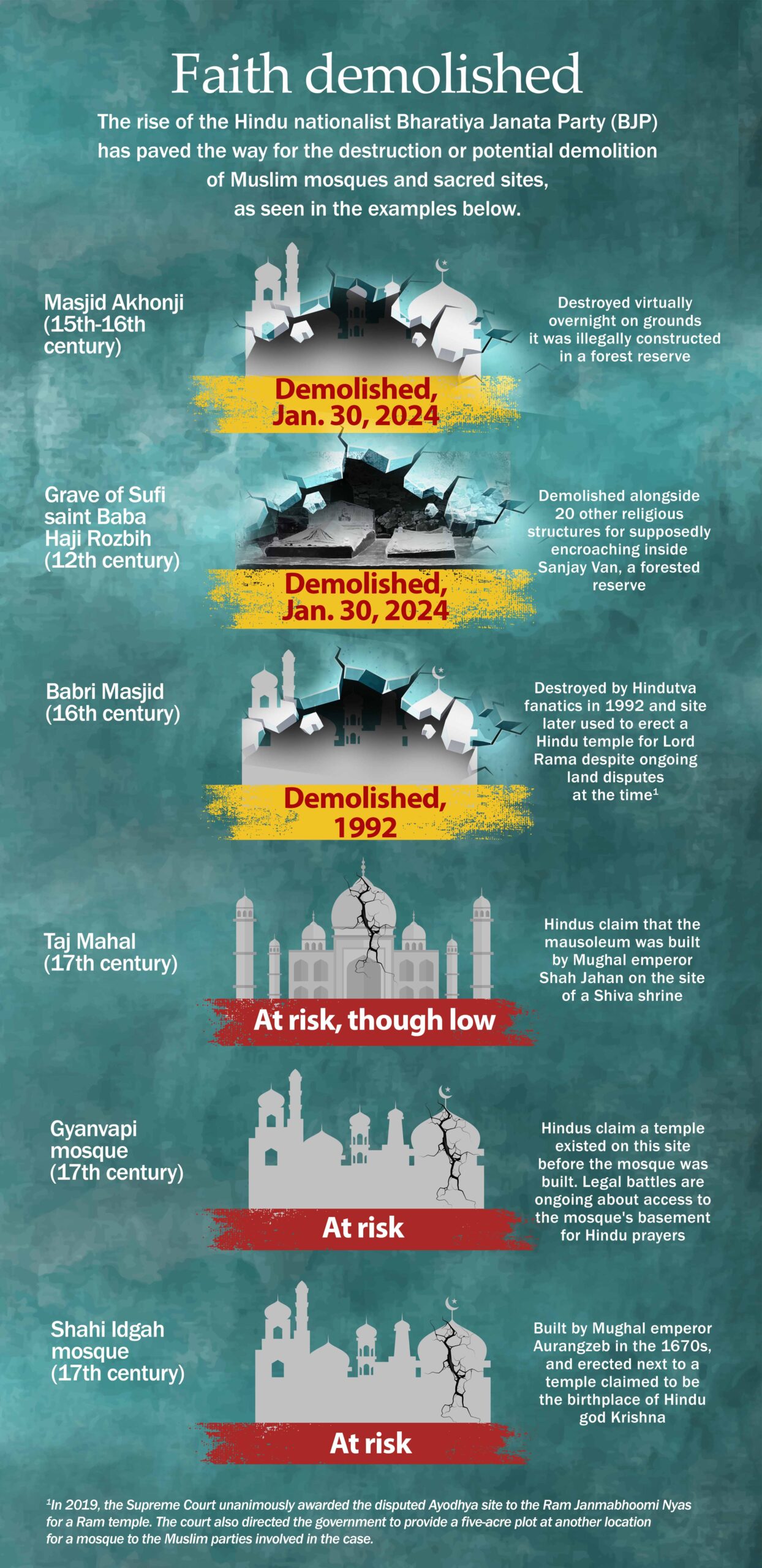

Since the BJP assumed power in 2014, there has been a consistent rise in violence and hate speech targeting India’s religious minorities, particularly Muslims. At the same time, a significant portion of the population’s clamor for a Hindu Rashtra or Hindu nation, has grown louder.

With the BJP predicted to win once more in the upcoming general election that will have seven phases, Muslims and other religious minorities such as Christians, Sikhs, and Buddhists fear they will be further stripped of their rights and that there will be more violent attacks from Hindu nationalists.

The Muslims, who make up more than 14 percent of the Indian population and are the country’s biggest religious minority, have borne the brunt of attacks from Hindutva supporters. BJP supporter Santosh Dubey, who was among the karsevaks (volunteers for religious causes) who demolished the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992, says that there is “nothing that belongs to Muslims in India. They should live like guests.”

Azam Qadri, president of the Sunni Central Board of Waqfs, Ayodhya, meanwhile, counters that the government has “betrayed” Muslims. “The government seems to belong only to Hindus, not to us,” he says. “We are facing injustice.”

Once a mosque, now a temple

Just this January, Modi personally went to Ayodhya, in India’s northern state of Uttar Pradesh, to inaugurate the Ram Mandir, the Hindu temple now occupying the space where the Babri Masjid once stood. On that day, Ayodhya was off-limits to everyone except for its residents and the few thousand individuals especially invited by the Indian government to witness the historic inauguration of the Ram Mandir.

As the festivities were going on at the country’s largest temple, residents of Ayodhya’s Muslim quarter, which is only a stone’s throw away from the grand structure, grappled with a sense of impending danger.

Many families, fearing for their children’s safety, chose to send the latter away from the city. Those who stayed woke up to fervent chanting of “Jai Shree Ram (Glory to Lord Rama).”

“I felt like they were instigating us,” says Shahjahan, a local resident, recounting a day marked by heightened anxiety. “We didn’t even open our windows that day. We were scared.”

“We were afraid of what might happen,” he continues. “The Hindu sentiment was at fever pitch. It’s difficult to even talk about it now. How can we not be afraid, given the news we see every day?”

Indeed, on Jan. 21, a day before the temple’s inauguration, Muslim neighborhoods across several states echoed with rightwing pop music and resounding “Jai Shri Ram” chants as Hindutva rallies went through them.

On Mumbai’s Mira Road, a rally escalated into violence that specifically targeted local Muslims, and resulted in the vandalism of shops and the destruction of vehicles. After two days of communal unrest, authorities initiated the bulldozing of supposedly illegal shops in the Muslim enclave Naya Nagar in Mira Road.

In Ayodhya itself, Muslims have been on their toes since Ram Madir’s inauguration. Just recently, a group of young men walking through crowds of devotees had kept shouting, “Ayodhya toh jhaanki hai, Kashi Mathura baaki hai (Ayodhya is merely a preview; Kashi and Mathura are yet to be conquered.)”

In Varanasi, more than 200 kms south of Ayodhya, the Gyanvapi Mosque stands near the Kashi Vishwanath Temple. Hindus have been calling for the mosque’s demolition, asserting it was built on a temple site. Recently, Hindus resumed prayers within the mosque’s cellar known as “Vyas Ji Ka Tehkhana.” The cellar had been unsealed by a district court after being shut down in 1993, following the Babri Masjid’s demolition.

Similarly, in Mathura, more than 530 kms west of Ayodhya, Hindu litigants argue that Emperor Aurangzeb demolished a temple to erect the Shahi Idgah Mosque in 1670, and claim the spot as Lord Krishna’s birthplace.

Deadly political strategy

The push for reclaiming the sites for the Hindu Shree Krishna Janmabhoomi and Kashi Vishwanath Temple had surged after the construction of Ram Mandir began. And since the Ayodhya temple’s consecration, incidents of violence and religious intolerance have markedly increased across India.

Mumbai-based writer-activist Ram Puniyani observes that every time there is a communal spectacle, the degree of hate goes up, which leads to sporadic violence in the South Asian nation.

“Hatred has been created in society,” he says. “Hate is the base of violence, and such events act as triggers for violence, which further deepens the hate. So it is the story of a deepening spiral of hate.”

Puniyani says that the Ram Mandir inauguration was highlighted to emphasize to Hindus that the BJP government is for them. Moreover, he tells ADC, “The inauguration of the temple is a culmination of the whole issue of Babri demolition, which was initiated to polarize society as a part of Hindu nationalist politics.”

Many observers say that Modi doesn’t really need more boosting to secure victory in the upcoming polls. Yet they assert that the temple’s inauguration was timed precisely for the elections. They say that this was also the case with the nationwide enforcement of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), a law that has been condemned for its alleged discrimination against Muslims, on March 11, or just days before the announcement of the general election dates.

Delhi-based media professional Noorail Khan says that the CAA’s implementation in the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections is part of the government’s strategy to have a decisive election win.

“Why wouldn’t Hindus vote?” asks Khan. “It (CAA) was promised to them, right? And the selling point was that Hindus are in danger, and CAA would definitely save them.”

Still, Khan says that in a country where she has to let go of her religious principles because “it will be a risk to my life, CAA is just a small addition to all those things that this government has been doing for a while.”

“The CAA is a totally unnecessary exercise, and excluding Muslims from citizenship is again a process meant to polarize the community before the elections,” says Ram Puniyani. He argues that the CAA marginalizes the Muslim community and intensifies fear among them, “while another section of the Hindu community will see that this government is doing the right thing for them by snubbing the Muslims.”

“This is for vote gain and to deepen the agenda of Hindu nationalism,” he says. “This is an add-on to the existing polarizing issues. They started with the Babri Masjid and later added different identity issues like the ‘love jihad,’ cow-beef, ‘corona jihad,’ and ‘land jihad,’ etcetera.”

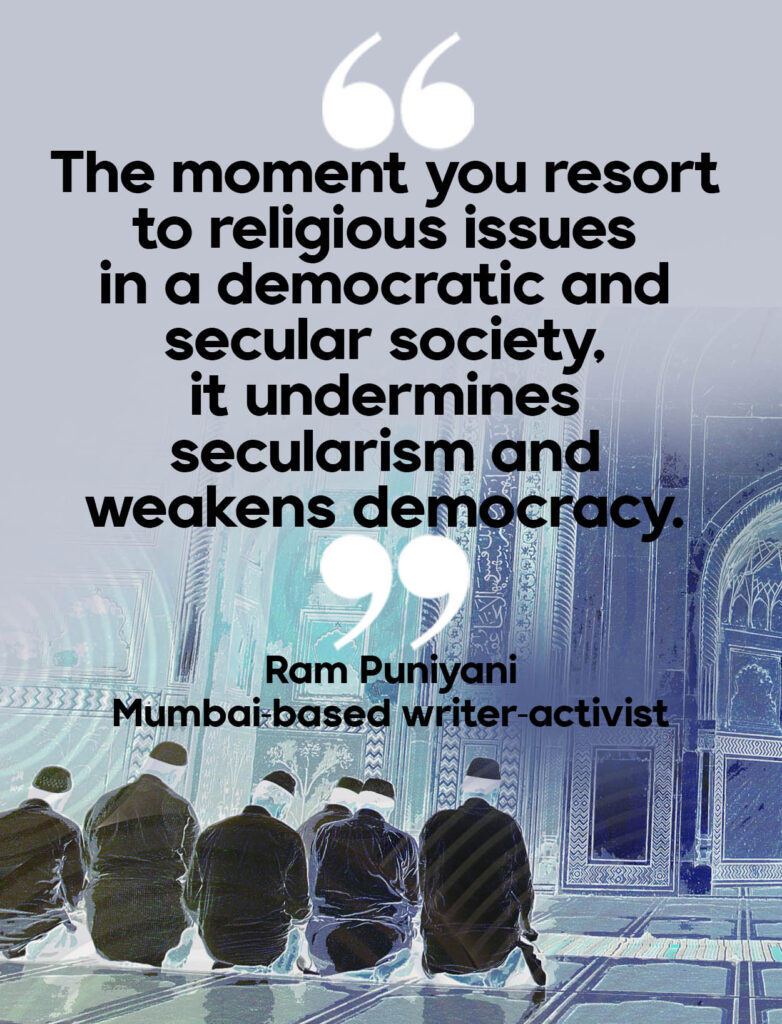

He says that the Ram Temple construction was also an add-on to the same divisive agenda of Hindu nationalism. Puniyani points out the danger beyond the violence: “The moment you resort to religious issues in a democratic and secular society, it undermines secularism and weakens democracy.”

Scared then, scared still

Back in Ayodhya, Qadri says that the Muslims there are scared. “They don’t want to face what they faced in 1992. And we don’t want our children to see the same situation.”

He is referring to the countrywide religious riots that followed the Babri Masjid’s demolition in December 1992, and which resulted in at least 2,000 people dead, most of them Muslim Indians. One of them was the father of Phool Jahan.

“He was burned alive,” Jahan says. “There was hardly anything left of his body.”

“My father’s absence still hurts me,” she says. “They [the government] built this mandir [temple] on their graves.”

She remembers being on their terrace with other Muslims from their neighborhood as they watched the mob climb the tomb and domes of the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque built during the Mughal era. It was the 6th of December, and Jahan was 10 years old. Ayodhya had taken on a menacing thrum as a frenzied mob breached barricades surrounding the mosque.

“I don’t remember vividly, but they were carrying huge hammers when they started demolishing the mosque,” recalls Jahan. “We were all scared then. We are all scared now.”

Last January, on the day of the temple’s inauguration, Phool Jahan sent her daughters away to her relatives. She says, “We are always scared. What if they [the mob] barge in and do something to us? At this point, we are in the middle of the fire.”

When Hindu devotees see Muslims, they chant “Jai Shri Ram” loudly as if to tease them, she says.

“Oftentimes, we are told to go to Pakistan,” says Jahan. “We are abused. We bear with it because we don’t want to get killed.”

Santosh Dubey, for his part, has no regrets about having a hand in the tearing down of Babri Masjid decades ago, or even for the violence afterward. A Shiv Sena leader at the time, Dubey is currently linked with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Hindu right-wing group that, along with BJP leaders, played a prominent role in advocating for the construction of the Ram temple.

“It was for a good cause, and I am proud of being a part of it,” he says. “We did that (demolition) for the samwidhan (constitution) of the country.”

Dubey says that a “’then BJP leader helped me arrange the weapons for the demolition” as he gathered people and mobilized them.

“BJP has the same kind of Hindutva in their hearts,” he says. “They are no different.”

Dubey remembers his sister making him swear on the rakhi (a tradition of bonding between sisters and brothers symbolized by a thread tied around the wrist) and saying he should return only after demolishing the structure.

“She said they would feel pride in ceremoniously welcoming him,” he recalls. “We have been raised in the tradition of killing and being killed here.”

Ayodhya autorickshaw driver Mohammad Saleem says that when he heard the Supreme Court’s decision to construct the Ram Mandir on the site of Babri Masjid in 2019, he was disappointed.

“I don’t feel happy at all, but we are helpless,” he says. “I even take the devotees to Mandir, what can we do? Nowadays, everything is politics here.” ◉

This article was produced in collaboration with Rough Cut Productions.