|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Days after arriving in Thailand, many of those who fled Myanmar to escape conscription struggle to get their bearings, and are visibly unable to think straight just yet. But some still attempt to work on a plan, even as they remain unsure if they will be able to stay in Thailand.

The Thais themselves – officials and ordinary folks alike – seem to have been taken off guard by the sudden influx of Myanmar nationals, even though they have had numerous surprise “visits” from the people of the troubled country next door for decades, including the small waves of refugees at the border since the Myanmar military staged a coup in February 2021.

Just last February, the Myanmar junta activated a long-dormant conscription law, triggering what now looks like a stealth exodus of mostly young Myanmar men to Thailand. But while Thai authorities have arrested several Myanmar nationals in the border areas for allegedly crossing without proper papers, there has yet to be any indication that Bangkok intends to come down hard on the hordes arriving at Thailand’s doorstep.

Still, as the number of Myanmar nationals in Thailand continues to swell, even those who have just arrived know that it is only a matter of time before the Thais’ wary welcome wears out. This has had the Myanmar new arrivals scrambling for ways to extend their stay in Thailand legally or at least until they are able to find another haven elsewhere.

In general, most are shunning the option of enrolling in a four-year university course and instead opting for short language courses that are available even in Thailand’s most prestigious educational institutions. Aside from financial considerations – in their haste, many had fled with little money in their pockets – the plan for many Myanmar citizens who have reached Thai soil seems to be, first, to secure a language-course slot that would give them reason to ask for a months-long visa, then find part-time jobs to help them survive and also finance their next moves. Many had been entrepreneurs or white-collar workers back in their homeland, but now they say they are willing to take on whatever job they can find.

A case in point is Shin Shin, who was a restaurateur in Mandalay. His business background seems to have come in handy, as he was able to get out of Myanmar with some savings and reached Thailand recently with a firm sketch of what to do next.

“I came with a modest amount of money that I believe can sustain me for about a year,” he says. “My immediate goal is to secure a visa for at least a year, possibly through a language-school program. During this period, I’ll be actively seeking employment.”

“My aim is to find a job that offers a work permit, even if it means transitioning to a blue-collar position for a couple of years,” continues Shin Shin, who is targeting work in the food-and-beverage service sector. “My mission for this year is clear: to secure a job, even though I anticipate it won’t be an easy task.”

Quests for cards, jobs

Another young man, this time from Ayeyarwady, is less prepared than Shin Shin, but lays out his plan nevertheless. He says, “I’m about to enter Thailand and will get a 14-day visa upon arrival. Obtaining a tourist visa in Yangon takes too long, and if I wait until after the water festival, I might already be on the military’s list for conscription, as we can’t trust the military’s actions.

“My plan is to travel to Laos to obtain a tourist visa and then extend it month by month through e-visa extensions,” the young man says. “During this time, I intend to search for a job and obtain the pink card, which is the most affordable option, to continue working. Despite having a well-paid job in Myanmar, I have no choice but to take on hard labor, which I had never imagined doing before.”

The “pink card” is the non-Thai identification card issued by the Thai government only once or twice a year, with the period for application lasting just 20 days each time. Moreover, it is issued only to those already with a work permit, and restricts the bearer to remain in the province that he or she said the card is for.

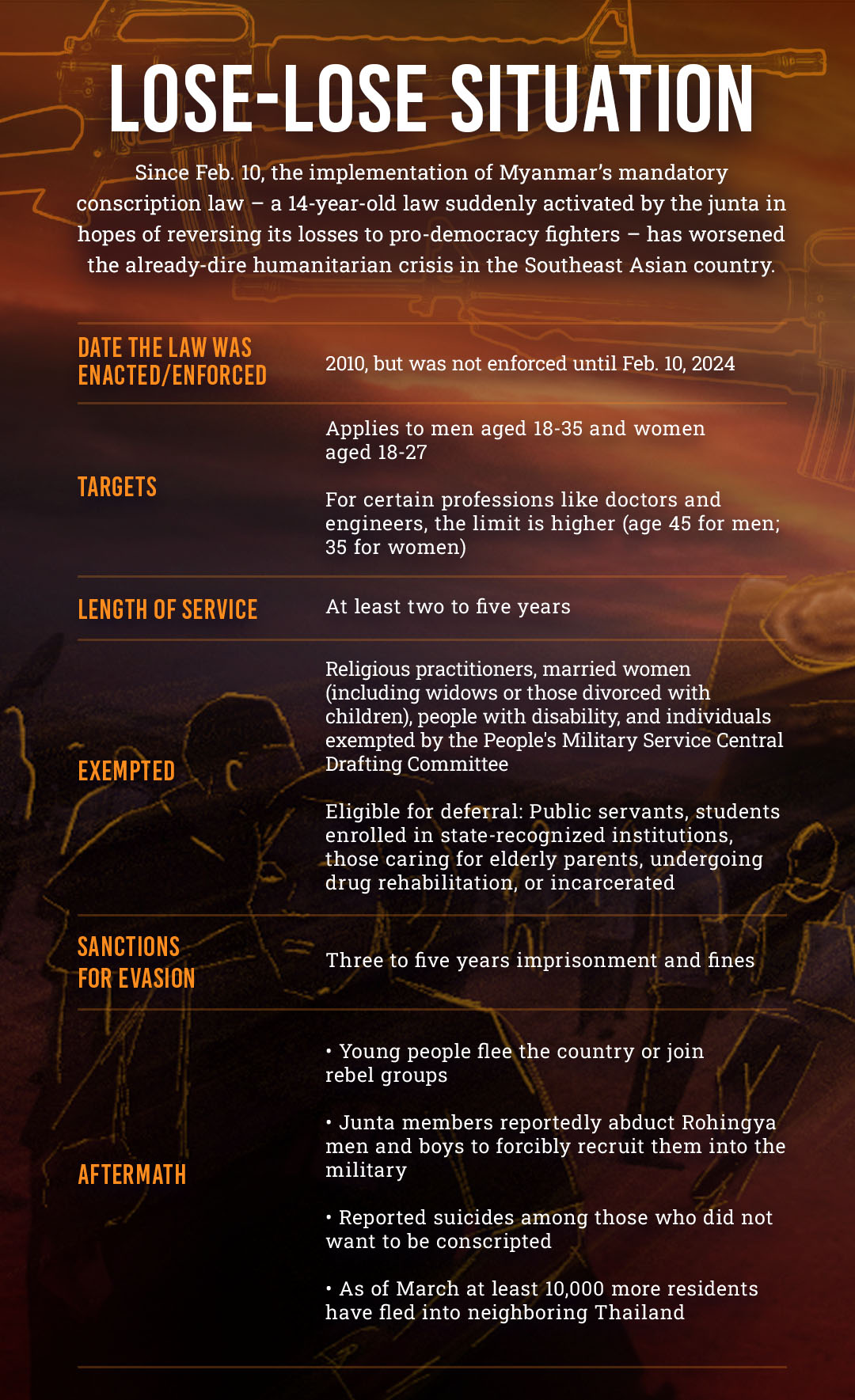

As for the water festival previously mentioned, the junta had said that the monthly recruitment of 5,000 people (or 60,000 a year) would start only after the water festival in April. Yet shortly after the announced implementation of the People’s Military Service Law on Feb. 10, people were already being called into service in some areas. This is why even though the military said female recruitment will not commence until after a year, many women eligible for conscription have been fleeing as well.

“I remember that night of the conscription law,” recounts Shin Shin. “I couldn’t sleep due to overwhelming frustration and anxiety. The thought of the border closing and travel restrictions scared me.”

“Initially,” he says, “I couldn’t think of how quickly the law would be implemented. However, our anxiety skyrocketed when they began compiling the eligible list and randomly selecting youths from the ward. Soldiers went door to door, summoning individuals to the ward administration office for a lucky draw to determine who would serve in the military. It was then I realized I could not live in the country anymore.”

Eligibles and exceptions

The law mandates the conscription of Myanmar male citizens who are 18 to 35 years old, as well as Myanmar women 18 to 27 years old. The compulsory military service supposedly lasts for two years. But those in select professions, such as doctors and engineers, are subject to a higher age limit and longer compulsory service. Junta spokesperson Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun has disclosed that of Myanmar’s 56 million people, roughly 14 million — 6.3 million men and 7.7 million women — are eligible for military service.

A migrant-assistance agent at the border area notes that lately, more and more Myanmar medical professionals are looking to go to Thailand. This is despite a hefty price tag, as the would-be migrants have to pay several bribes throughout the process. The bribes medical professionals have to fork over are larger compared to those imposed on other migrants, because the risk is higher; the military has been actively monitoring and compiling data on their sector, among other professions.

“Many doctors, both CDM (Civil Disobedience Movement) and non-CDM, have observed that their families often sell almost everything they own just to afford traveling across the land border,” comments another agent.“ Crossing without a passport is even more costly. Sadly, once they leave their profession, there’s hardly any chance they can continue practicing medicine here in Thailand.”

Exceptions to the conscription rule include members of the religious community such as priests, monks, and nuns from Buddhism, Christianity, and Hinduism (interestingly, the law does not mention Islam); married and divorced women with children; people with disabilities; and those deemed unfit to serve by the recruitment committee’s medical assessment team. The law also cites those who are “made exempted by the recruitment committee as required.” Some people say students and government servants could delay their military service as well, but this is not spelled out in the law.

Entering monkhood and the nunnery at this point so as not to serve in the military is not an option, since the military requires members of the religious community to have identification cards that take years to acquire. Meanwhile, those caught evading conscription may be jailed for three to five years aside from being fined. People faking disabilities to escape recruitment may also be meted a prison term of five years.

Popular choice

Some of those who do not want to be recruited into the Tatmadaw, as the Myanmar military is known, have been joining the ethnic armies or the People’s Defense Force (PDF) instead. Others have opted to just keep on moving within Myanmar, although that may now be fraught with risk; domestic travelers face heightened document scrutiny, as the military broadens efforts to restrict movement and disrupt the plans of those intending to leave Myanmar.

The bulk of those who do not want to serve in the Myanmar military, though, are heading toward Thailand. According to a Deutsche Welle report published in mid-March, a Thai labor activist had estimated that some 10,000 Myanmar nationals had already crossed the border into Thailand since the Feb. 10 announcement.

A visa agent based in Mae Sai, on the Thai side of the border, says that around 800 individuals are crossing the border daily.

“I don’t have the exact number of visa applications we’ve had to handle,” says the agent, “but it’s increased threefold since the implementation of the conscription law.”

Aside from its proximity to Myanmar, Thailand’s sizeable Myanmar migrant community is another come-on for Myanmar nationals seeking to escape conscription. Myanmar citizens in Thailand are estimated to be between two million and three million in number, including those without legal papers. Human Rights Watch says that some 45,000 Myanmar refugees have fled to Thailand since the February 2021 military takeover.

The Myanmar diaspora in Thailand has become a communal safety net for the new arrivals. Local Myanmar organizations, for instance, have been extending humanitarian assistance to those displaced by the conscription law. One of them is the Mae Sot-based Myanmar Foundation, which offers cash assistance to cover basic food and living expenses for those affected by the junta’s freshly implemented rule.

Individuals have also stepped in, such as independent volunteer Ma Coral, who helps new migrants find housing and employment opportunities, and connects them with relevant contacts for safe passage and travel.

Individuals have also stepped in, such as independent volunteer Ma Coral, who helps new migrants find housing and employment opportunities, and connects them with relevant contacts for safe passage and travel.

Kaung Kaung, who has been living in Thailand for more than two years as a student, also makes it a point to lend a helping hand to the newcomers.

“I’ve been providing my room to newly displaced individuals who’ve had to relocate due to the conscription law, free of charge,” he says. “It’s the least I can do. I’ve also been offering information and whatever assistance I can provide.

He adds: “They’re welcome to stay in my room until they find their own accommodations and sort out their visa matters. It brings me joy to lend a helping hand to my friends during this challenging time.”

Chan Chan, who admits he left Myanmar to avoid becoming a military conscript, says: “Despite numerous options, we chose Thailand because it’s our neighboring country and we already have established connections here. Opting for the quickest escape, I find comfort and relief in heading somewhere familiar, where I have friends and connections.

“Upon arrival, I felt mentally secure,” he says. “Yet strangely, I still feel uncertainties and insecurity because I have no idea what will happen next.” ◉