|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This article is the fourth in a 10-part series collectively themed “Fostering Democracy Movements,” an Asia Democracy Network special 10th anniversary report produced by the Asia Democracy Chronicles. The release of this series is also in commemoration of Human Rights Day on December 10, 2023. The entire report can be downloaded here.

T

he meteoric rise of China as an economic and political power on the world stage in recent years has had a profound impact on the state of democracy in Asia – and it’s not about to stop exerting its influence in the region anytime soon.

At the World Political Parties High-Level Meeting in March 2023, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced his “Global Civilization Initiative,” which supposedly aims to advocate respect for the diversity of civilizations. As with China’s Global Development Initiative in 2021 and the Global Security Initiative in 2022 ,Xi is positioning GCI as a politically agnostic project while prescribing an “Asian” path to modernity.

In a clear jab at China’s hegemon rivals, Xi said that “[c]ountries need to … refrain from imposing their own values or models on others and from stoking ideological confrontation.”

This appeal to value-neutral economic deals pokes at the heart of the increasing disentanglement of democratic values and economic prosperity in Asia. But the allure of China’s “alternative” model is further magnified by the Asian giant’s economic might, which enables it to exert considerable influence over other nations, especially those grappling with internal economic and political challenges.

It hasn’t helped that the blitz-like return of Cold War geopolitics in the region has further eroded the already strained social contracts in democratizing countries. As tensions between the United States and China intensify, militaristic authoritarians have been having an easier time finding backers willing to finance their heavy-handed rule.

Belting it out

The last decade saw China’s global rise through the lens of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi’s trillion-dollar project for his country to invest outside its borders and foster “regional connectivity.” Cumulatively, China has already inked deals in more than 100 countries valued at over US$965 billion, a third of which has gone to Asia.

| Belt and Road investments |

| Graph 1: The Belt and Road Initiative is costing China US$965 billion in 2023, a third of which has been allocated for Asia. |

| Source: China Global Investment Tracker |

The big-ticket projects often associated with China’s BRI have been, for the most part, widely criticized for their opaque processes, debt-trap characteristics, and penchant for non-renewable energy. From the Hambantota port fiasco in Sri Lanka to the corruption-mired unfinished railways in Malaysia, the BRI portfolio in Asia was met with resistance from recipient communities, rivals, and partners alike.

| BRI project portfolio in Asia |

| Graph 2: China’s Belt and Road projects in Asia by sector |

| Source: China Global Investment Tracker |

A paper published in July 2020 by the Journal of International Business Policy suggested that these huge projects were more likely to be planned and conducted in countries that are autocratizing, i.e., states with record abuses of human rights and weaker labor standards, freedom of opinion and information, and rights to peaceful assembly and association. This is because autocratic regimes are more likely to accommodate conditions bordering on being predatory that come with China’s foreign direct investments.

Marketa Maria Jerabek of the University of São Paulo’s Centre of International Politics and Economics (NEPEI-USP) also noted that in countries with significant BRI investments, media self-censorship and repression against civil society have worsened over time. Indeed, the top five countries in Asia that received Chinese investments in the last 10 years have been on an autocratic path.

| China’s Southeast Asia investments |

| Graph 3: Over half of cumulative BRI investments went to Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia. |

| Source: China Global Investment Tracker |

Emerging rivalry

Surprisingly, in the last few years, India has turned into one of BRI’s biggest critics. Despite being among the founders of the China-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, otherwise known as AIIB, which bankrolled much of BRI’s portfolio, India has been vocal in opposing China’s “string of pearls” strategy.

Apparently, India has been most upset with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which cuts through the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir along the Line of Actual Control.

The growing crack in Sino-Indian relations came to the fore when India refused to join the China-led regional trade bloc, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2020, following a border battle in Galwan Valley. More recently, the world’s two most populous countries also expressed diverging views on whether to position the BRICS economic bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) as a direct rival of the United States.

As tensions grow between the United States and China, India under Narendra Modi has positioned itself as an Asian counterweight to the latter superpower. The tactic seems to be working, with the United States doubling down on taking Modi on as a junior partner, despite growing criticism from both civil society and its allies. Last year, not only was the United States India’s third biggest arms supplier, its economic trade with the world’s largest democracy surpassed China for the first time in years.

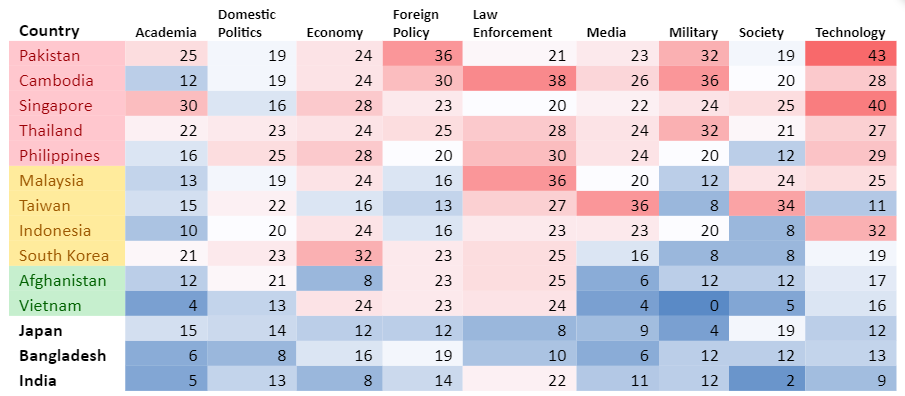

| Measuring China’s influence in Asia |

|

| Graph 4: China wields considerable but varying influence in the region across multiple domains, with five countries more affected than others. |

| Source: DoubleThink Lab (2022) |

The Quad, the map, and the pivot

In March 2021, just months after the China-India border skirmishes, U.S. President Joe Biden called for a virtual meeting of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. The Quad – a resurrected formation composed of the United States, Japan, Australia, and India – has since been dubbed the “Asian NATO,” despite having no formal trade or security agreements in place. This came after Washington announced that it was operationalizing its Obama-era strategy of “pivot to the Indo-Pacific.”

The subsequent Quad agreements on maritime security, as well as the numerous economic partnerships and multilateral military deals at their heels, directly aim to “contain China” and its growing influence in the region.

From the nebulous 14-country Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity economic treaty to new military agreements in the Pacific area, the United States has been creating new bases and deploying more investments in countries neighboring China.

While New Zealand, Vietnam, and South Korea are increasingly aligning with the U.S.-led Quad as the “Quad Plus,” the Philippines, Taiwan, and, to some extent, Indonesia are minting new military deals in the South China Sea.

Japan, notably, has found international backing from its U.S. and Australian allies in drawing up the biggest military ramp-up since World War II – from zero to US$320 billion in just five years. Speaking to the press last year, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said that “[t]he strategic challenge posed by China is the biggest Japan has ever faced.”

For years, China has been illegally claiming parts of the South China Sea through a fictional nine-dash line. The claim, which was overruled by the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in favor of the Philippines in 2016, has created one of the deadliest zones for fishers from neighboring countries, including Japan, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Over the past few years, China has been harassing Filipino fishermen making a living in the Philippine-exclusive maritime zones.

End of ambivalence?

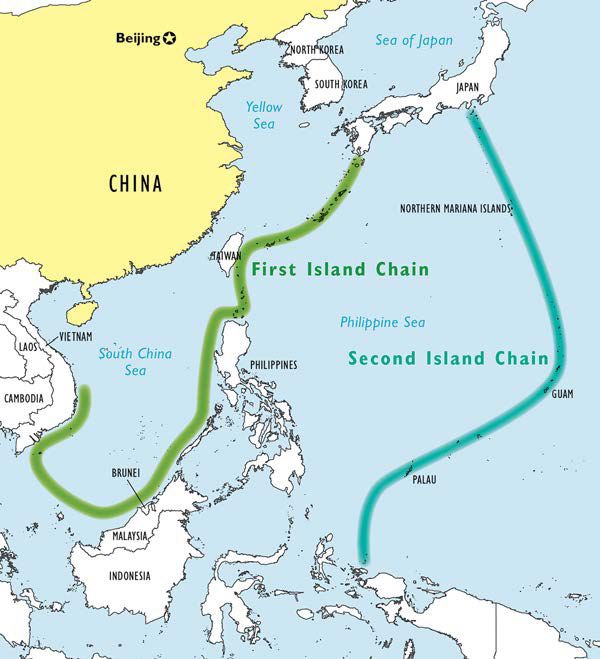

Mimicking China’s aggressive stance in the South China Sea, the United States has deployed what it calls the “First Island Chain” strategy. The Western superpower aims to transform Japan, Taiwan, the islands of the Philippines, and Indonesia into a “line of defense” for neighboring countries.

Central to this strategy is Taiwan. Since the controversial August 2022 visit of then-U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan, Washington has dropped its decades-long stance of “strategic ambivalence” in support of Taiwan’s independence from China.

Biden has said in no uncertain terms that the United States will defend Taiwan from a Chinese invasion. In fact, most of the talks about militarizing the South China Sea have been made in the name of Taiwan’s defense.

As if in response, China last August released yet another version of its map, this time adding a tenth line, clearly crossing the first-island chain strategy along Taiwan’s waters.

This increasingly hostile confrontation, proxied by naval skirmishes and occasional aerial displays, is also signaling an end to the era of geopolitical ambivalence in the region. More and more governments are being forced into lockstep with either the United States or China.

Whether intentional or not, both rivaling powers have ended up backing autocratic regimes in Asia against one another. For example, the Philippine government under Ferdinand Marcos Jr. – namesake of his father, the late dictator – currently enjoys billions of dollars in military and economic assistance from the United States, despite so far showing mostly autocratic policies and norms. China meanwhile has been backing Cambodia’s Hun Sen and brokering peace for the Myanmar junta to secure its rear.

Democracy in Asia is already in crisis. But the shifting balance of power in the region, prodded by tight-rope geopolitics, is only accelerating the erosion of democratic values all the more. ◉