|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

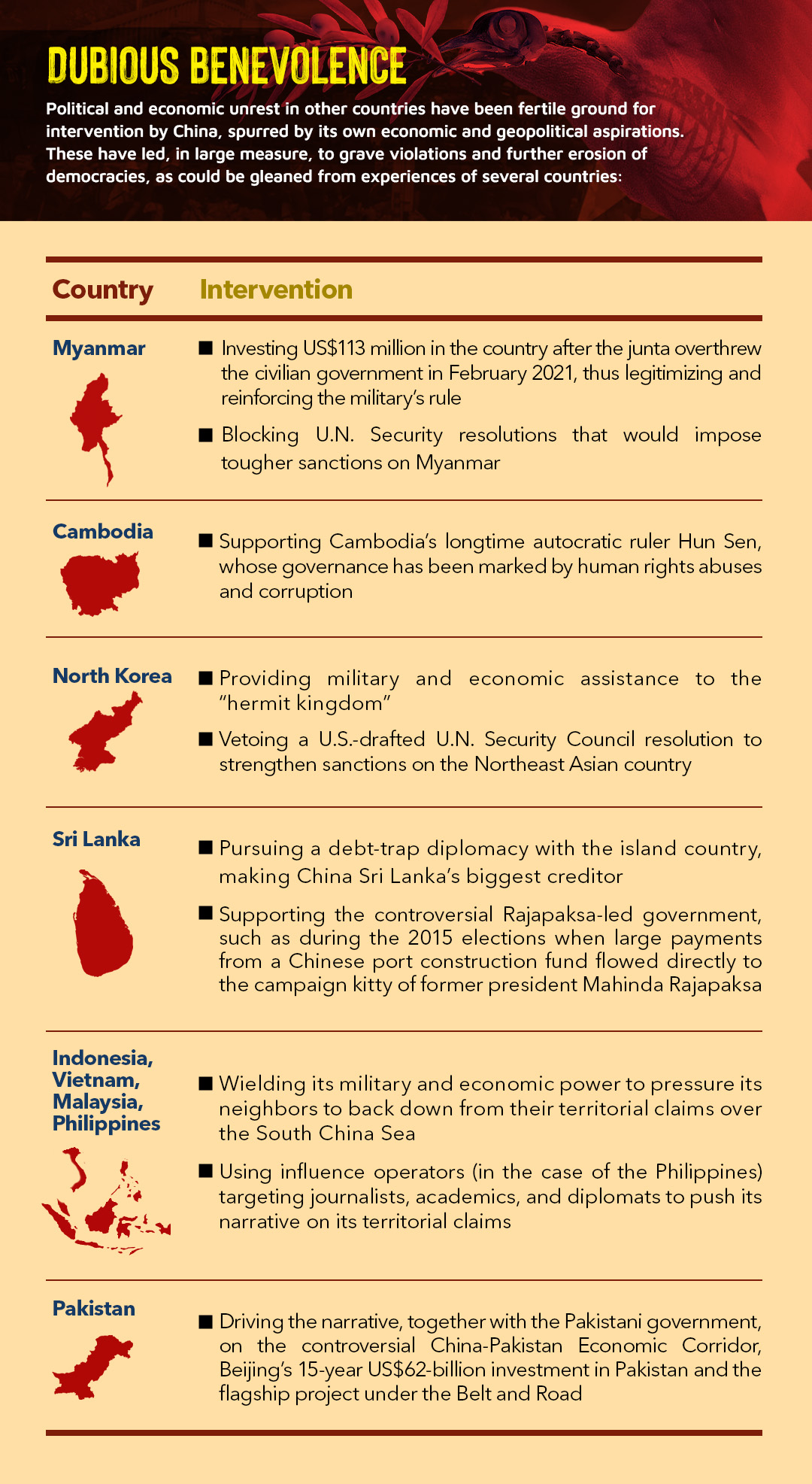

The talks brokered by China between Myanmar’s military junta and a tight selection of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in Myanmar went nowhere fast, but the event did succeed in highlighting Beijing’s continued influence on the latter.

In fact, while Beijing portrays itself as a friend of the junta, it is no secret that it has been supporting several EAOs since they began fighting Myanmar’s central government decades ago. And now, analysts say, after assessing that the junta is unable to maintain political stability, Beijing is increasing its engagement with these groups.

This does not sit well with most of Myanmar’s people, who support the civilian government that the military overthrew in February 2021. Already upset with China’s perceived approval of the coup, they see Beijing’s latest move as an affront to the People’s Defense Force (PDF) that had grown out of the pro-democracy movement.

“China’s intervention for peace between the Brotherhood Alliance and military could impact the revolution,” says Ko Kyaw, a member of the armed resistance forces from Central Myanmar. “We regard this effort as an action of disruption against the revolution, and it will increase more negative views toward China.”

The “alliance” he is referring to is the Three Brotherhood Alliance composed of the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). All three Alliance members were invited by China to meet for talks with the junta’s peace delegation last June.

While not officially aligned with the PDF, the members of the Three Brotherhood Alliance have been actively supporting groups involved in what is dubbed the Myanmar Spring Revolution. They have played significant roles in supplying weapons and training to newly formed resistance groups. The three EAOs represent central nodes in the emerging network of revolutionary groups challenging the junta’s authority, which explains why China’s peace-making efforts between these EAOs and the junta are being seen as counter-revolutionary.

A valuable Corridor

In truth, the growing ties between the EAOs and the pro-democracy fighters are among the reasons why the military has been struggling to gain ground against the PDF. This reality has not been lost on China, apparently, which analysts say is precisely why it decided to broker the talks.

“Surely, China is quite aware of the decline of capacity and performance of the military,” says a Northern Shan-based conflict analyst who has close ties to EAOs in that area. “To defend its interests and protect its businesses, it has increased engagement with the ethnic armed groups, wearing not only the supporter’s hat of these armed groups, but also the hat of mediator between these groups and the military regime.”

“China is aware of and concerned about the military regime’s inability to maintain stability,” another conflict analyst and China watcher says. “It is unsure whether the military can keep Chinese projects and interests safe in the country, (including) stabilizing the border area and defending business in the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC).”

“China is aware of and concerned about the military regime’s inability to maintain stability,” another conflict analyst and China watcher says. “It is unsure whether the military can keep Chinese projects and interests safe in the country, (including) stabilizing the border area and defending business in the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC).”

The CMEC is a series of infrastructure, energy, and industrial projects that connects Kunming in China’s southwestern province of Yunnan to Mandalay in central Myanmar, and extends to Yangon and Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone on the Bay of Bengal in Rakhine state. A major reason for China’s interest in seeing the Corridor — which already has oil and gas pipelines running from Kunming to Kyaukphyu — finished is that it will give it a direct passageway to the Indian Ocean.

Interestingly, the EAOs Beijing invited to the talks with the junta delegation control areas that the Corridor traverses: AA operates in Rakhine State, while TNLA and MNDAA are both based in Shan state. The three EAOs are also part of the seven-member Federal Peace Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC). Save for the Arakan Army, FPNCC members operate in either Kachin state or Shan state, both of which border China.

China has ties with all the FPNCC members, albeit in varying degrees. Those in the border areas even use the Chinese yuan as currency. Of the FPNCC members, however, the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) in Shan State are considered to have the strongest relations with Beijing, which provide them diplomatic and physical support. Both UWSA and NDAA also reportedly maintain considerable economic relations with China. Within the areas controlled by these two EAOs, Chinese is the second official language.

Polls as exit strategy?

Some analysts say that China is keen to keep the peace because it does not want to see thousands of refugees pouring into its territory, just like what is happening on the Thai-Myanmar border. These observers nevertheless agree that Chinese investments in Myanmar are among the primary reasons for Beijing’s push for EAOs to talk to the junta.

Beijing, of course, could well have just asked the EAOs to hold off any attacks on Chinese interests in Myanmar. But in an apparent effort to avoid putting its eggs in a single basket, Beijing also reached out to the junta and assured it of support for the elections that the military leaders have been saying are forthcoming.

At least one expert, though, says that Beijing’s support of polls in Myanmar is not just a public relations stunt. An experienced China hand from a local think tank, the analyst says that Beijing sees the elections as a proper political exit for the junta.

Last July, the International Liaison Department of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee invited Myanmar’s Union Election Commission (UEC) to participate in a study tour. This tour had followed discussions between Myanmar’s Consul General in Nanning and a Deputy Director General of the Foreign Affairs Office of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region on the possibility of Myanmar’s elections.

A month after, it was the turn of the leaders of Myanmar’s ethnic political parties to be invited for discussions and tours. In preparation for all these, China’s Ambassador to Myanmar, Chen Hai, held two meetings with the UEC chairman in 2022 and 2023, with the talks focusing on political party status, voter-list preparation, and election-law development. Says the China analyst: “China wants the military regime to use these platforms to persuade and convince the ethnic armed groups to involve and support the plan of election, with minimum disturbance.”

China “really wants to end the conflicts in Myanmar through elections, which could return the country to a situation similar to that in 2011,” she asserts. That year saw the transfer of power from the former military regime to a nominally civilian government following the November 2010 elections.

Friends and foes

Twelve years ago, Myanmar began its transition into the military’s idea of democracy, which led to a lull in political unrest. While those calling for democracy had not formed armed groups at the time, there were at least 20 ethnic armed organizations – down from nearly a hundred right after Myanmar (then called Burma) gained independence in 1947 – that were active.

Then as now, the EAOs demanded self-determination. Only one, however, has achieved something close to that: UWSA, ruling the Wa Self-Administered Division in northern Shan State.

Along with NDAA and another FPNCC member, the Shan State Progressive Party, UWSA has been reported to have been negotiating with the junta, putting down further demands. This is why Beijing did not bother inviting them to the talks. Yet another FPNCC member, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), was left out of the talks as well, but for a far different reason: it has publicly declared itself in support of the PDF. A January 2023 Frontier article reported a KIA officer as saying, “China is a powerful and important friend for us. But I understand that the Myanmar military is an evil enemy that the KIA must completely defeat.”

And so it came down to just the Three Brotherhood Alliance members meeting with the junta delegation for the Beijing-brokered talks. A source close to the three EAOs confirms that a request for support for the elections came up during the discussions, but that the representatives of the Alliance members did not comment on the proposal. The day after the talks, the military had an armed confrontation with the MNDAA. It also has had frequent clashes since with TNLA.

At the official celebration of the 60th Ta’ang National Revolution Day last January, TNLA Chairman Tar Aik Bong reportedly declared: “The Military Council regime is preparing to hold sham elections in August 2023, with the aim of maintaining the power of successive military dictatorships. Any kind of support that would prolong the reign of the junta should be effectively blocked in their own territories by the relevant forces.”

Beijing, however, did gain something for playing broker. Weeks after the talks, the Three Brotherhood Alliance released an official joint warning that they would “take effective actions against those trying to damage international investments.” According to the online publication Irrawaddy, TNLA spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Mai Aik Kyaw said the statement had been released at Beijing’s request, indicating that the “investments” referred to Chinese ones.

At the 2023 GMS (Greater Mekong Subregion) Economic Corridor Administrators’ Forum in China’s Yunnan Province last August, Myanmar’s Investment and Foreign Trade Relations Minister Kan Zaw meantime noted that China had 597 investment projects in Myanmar. These made up “23.5 percent of the total amount of foreign investment” in Myanmar, he said, with a total value of “US$21.863 billion.”

The minister was also quoted as saying Myanmar will always be thankful to China. ◉

Jesua Lynn is an independent researcher and peace-education trainer from Myanmar. He is a regular contributor to Asia Democracy Chronicles and writes for other publications such as Peace Insight and Gen-Zine, focusing on human rights, youth activism, and peace-building.