|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

E

lections are supposed to give people a chance to have a say in how their country should be run and for changes to take place. But as nations across South Asia prepare for their respective upcoming polls, there is little indication that any real transformation will happen, leaving religious minorities in these countries increasingly worried.

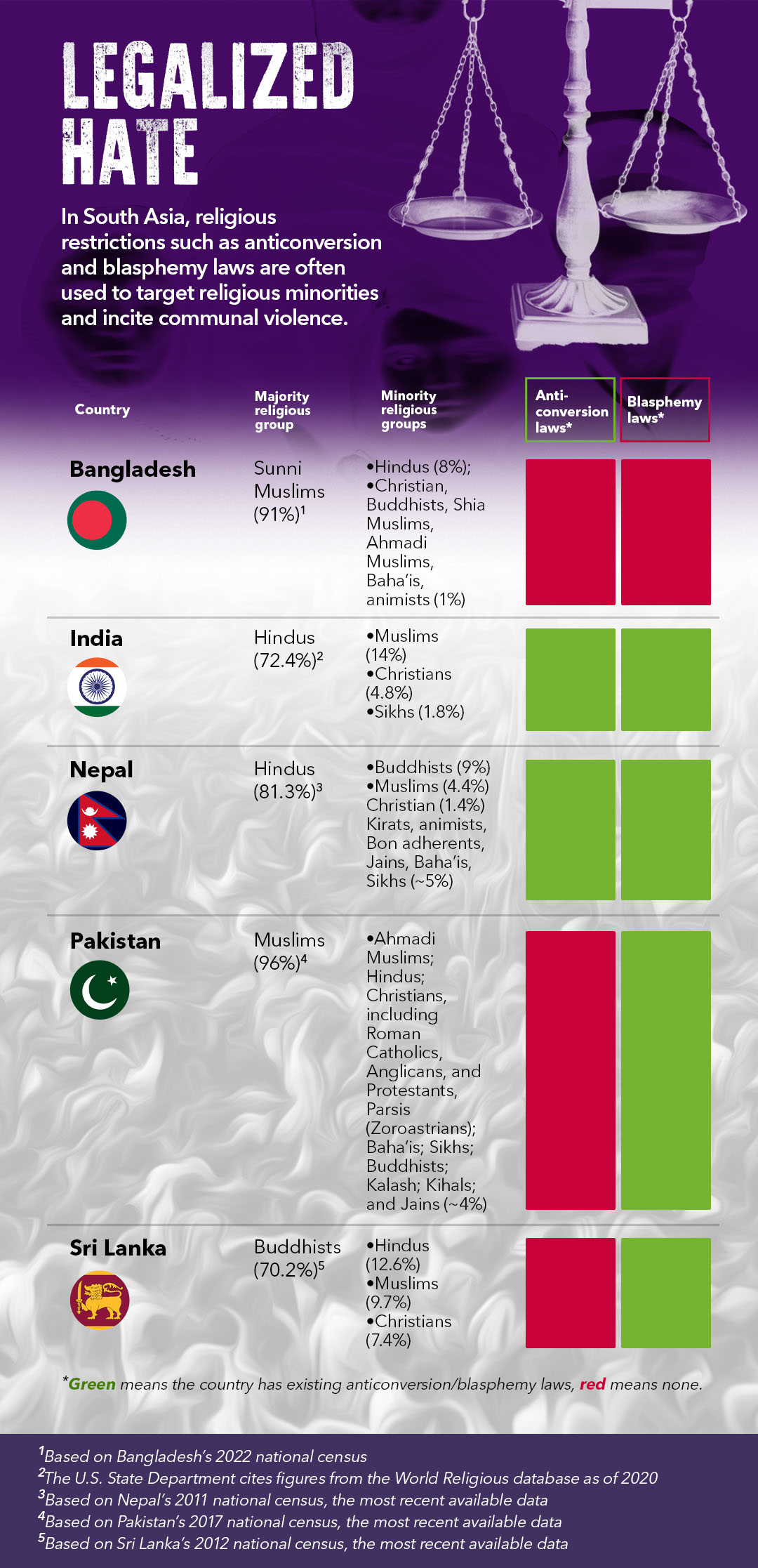

Pakistan is scheduled to hold national elections this November, while Bangladesh’s prime minister has announced that her country will have its general polls in January. National elections are also supposed to take place in India and Sri Lanka next year. While it can only be expected that ruling parties will try to stay in power, such attempts in South Asia have now included attacks on members of religious minorities.

In the runup to the elections across the region, Ashok Swain, head of the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Sweden’s Uppsala University, predicts: “The rightwing politicians are going to openly and unashamedly exploit existing fault lines to rally support or divert attention from their failures.

“While communal violence has occurred in these countries in the past,” he adds, “the current landscape might be set apart by several factors. The rise of majoritarian politics and rapid spread of information through social media and digital platforms can amplify tensions and contribute to the swift escalation of conflicts.”

University of California at Berkeley scholar Angana Chatterji meanwhile says that the upcoming elections may trigger a ramping up in the battle for the “Hindu nation” in India. This, she says, could lead to experiments in forcible assimilation, presumptive statelessness, and calls for the ethnic cleansing of Christians and genocide of Muslims there.

As it is, South Asia – which has a population of nearly two billion – has already been seeing a rise in communal violence in the last several years.

In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has held power since 2014 and has been accused of ostracizing the country’s largest religious minority, its 213 million Muslims. Mosques have been vandalized, madrasas shut, Muslim men randomly arrested on charges of converting Hindu women to Islam, and Muslims labeled as “foreigners” under the garb of a citizens’ national register. But Christians have not been spared either. The Delhi-based rights group United Christian Forum (UCF) recorded 598 incidents of violence against Christians from 21 states last year. In the first half of 2023 alone, UCF data show, the community faced over 400 hate crimes, averaging more than two incidents per day.

In the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the attacks on religious minorities such as Hindus and Christians are on the rise as well. According to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), religious freedom conditions in the country “continue to deteriorate.” It says in its 2023 report, religious minorities were “subject to frequent attacks and threats, including accusations of blasphemy, targeted killings, lynchings, mob violence, forced conversions, sexual violence against women and girls, and desecration of houses of worship and cemeteries.”

In Sri Lanka, communal violence, largely targeting Muslims, started allegedly by a few radical Buddhist monks seven years ago. With their proximity to the former president Mahinda Rajapaksa, the monks openly spread hatred against Muslims on social media. The rage has since also spilled on the country’s streets. In 2019, after the Easter bombing that killed more than 250 people, many Muslim men were randomly arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act; they remained in pretrial detention lasting many years.

Attacks on minorities in Bangladesh have been a matter of grave concern as well among rights’ defenders. This is so even as Bangladesh is a secular state like India, and is unlike Pakistan and Sri Lanka, which have constitutions that are expressly biased toward the respective dominant religion in these two countries.

Roots in the past

Political scientists believe that the communal violence in South Asia is partly a result of the region’s colonial past. For sure, though, Hindu-Muslim riots in India happened before the British came to the subcontinent. In the 14th century, the Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta described how in Mangalore town in India, “war frequently breaks out between them (the Muslims) and the (Hindu) inhabitants of the town; but the Sultan (the Hindu King) keeps them at peace because he needs the merchants.” Studies have also established that the decline of the Mughal Empire and rise of the Marathas in the late 17th century sowed the seeds of Hindu nationalism, the proximate cause of contemporary riots.

Still, social scientists point to the British as having “constructed” modern Hindu and Muslim identities through the first scientific census of 1871, allegedly using a “divide-and-rule” policy to promote violence between the two communities so that it could maintain power. The set-up engendered ethnic animosities, as rival communities jockeyed for position, often in order to receive patronage from the colonial state. Then came the 1947 partition of India, which witnessed hundreds of thousands of Hindus and Muslims killed during riots, ethnic cleansings, and cross-border migrations.

But for Ajay Gudavarthy, political studies associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, “it is an open debate whether the communal violence we are witnessing in these places is a direct result of our history and interventions of the colonial state or whether they are relatively new conflicts. It is also not clear if the conflicts are essentially cultural in nature or generated more through political interventions and mobilization.”

At the very least, though, he says that on most occasions in South Asia, violence is rarely spontaneous and mostly “organized” by vested interests. “People, cutting across religions, become either mute spectators or hapless participants,” says Gudavarthy.

Michael Williams, UCF’s founder-president, observes that in India these days, the voice of the mob has been given respect and dignity and the purveyors of the right-wing ideology have been rewarded. And while there is only a “small minority within the majority which aligns with the ideology,” Williams says, “that small number is enough for consuming the nation and forcing it to get into a dangerous trajectory.”

A worldwide trend?

Some experts say that the violence in South Asia echoes the global trend of the dominance of identity-based right-wing ideology that emerged following the economic recession in 2008.

Ideally, a sharp economic decline gives rise to progressive movements out of the large discontent. But the collapse of socialism and the rise of neo-liberal hegemony, where anything that could be identified as Left was seen as suspect, have given space to right-wing identity-based ideology, which always creates the “other” as the reason of all sufferings, experts say.

In most cases, says historian Mridula Mukherjee, people’s anger is turned against communities, largely the immigrants or the religious minorities, who are labelled as the “other,” or the “enemy.”

For example, in Italy, Matteo Salvini, who spearheaded an anti-immigration policy that barred humanitarian rescue ships from Italian ports, is now the country’s deputy prime minister. In Sweden, an anti-immigrant party, Sweden Democrats, is currently the second largest party in the parliament.

In India, too, the rise of far-right forces has created the “other.” In an August 2021 podcast interview with the USCIRF, Farahnaz Ispahani, Public Policy Fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., commented that the “otherization of minorities (is) a way to mobilize the majority.”

“So to get Hindu votes in India,” she said, “you tell your voters that Christians and Muslims have it better than them, that Indian Christians have ties with Western Christianity and are therefore less Indian, and Muslims – even if they have been in India for centuries – are somehow from the Middle East and have sympathies with Pakistan.”

She added that a similar tactic is in use in Pakistan, where “the majority is being made to hate and fear the minorities.” Ispahani, who used to be a member of the Pakistani parliament, also noted, “Islamism is also a way to keep in check political parties that may challenge the military’s domination with democratic or liberal demands.”

‘Updated’ hate politics

“The region’s diversity, history of partition, and the rise of rightwing populist politics have created a volatile environment in which the majoritarian groups vie to capture total power and influence, often leading to violent conflicts,” remarks Swain of Uppsala University.

“What is new,” he continues, “is that in countries like India, religious leaders have also become political leaders and political leaders have become religious leaders.” One prominent example, Swain says, is the induction of saffron-clad BJP politician Yogi Adityanath as the chief minister of northern state Uttar Pradesh.

Another factor setting the current violence apart from that of the past is “state complicity.” Or as Ispahani put it, “governments that are supposed to protect the minorities are being made vehicles of persecution.”

In India, Chatterji says that the “apparatus of Hindu nationalism is operationalized by its parliamentary wing and grassroots cadre, imperiling the sanctity of Muslims.”

“The narratives of Hindutva seeks to popularize the myth of Hindu culture as under siege, Hindu women as vulnerable, and justify the Hindu male as the protector-aggressor,” she says. “It scripts Hindu heteronormative aggression as patriotic. It conjoins hyper-masculinity with majoritarian nationalism. This is a key component of the platform for building a Hindu state.”

“It endangers religious freedom, and criminalizes inter-faith marriage and spousal relationships, and women’s agency and self-determination,” says Chatterji. “It promotes casteism. It justifies the assault, intimidation, and incarceration of those whose actions are deemed ‘seditious’.”

“There is greater justification to move away from secular ethos to majoritarianism,” Gudvarthy says of the South Asian communal violence. “Violence is perpetuated also through legal methods, extraordinary laws, and skewed and selective implementation of laws. State complicity produces greater space for violence assuming genocidal proportions.”

The risk of religious minorities coming under attack also increases whenever those in power feel their rule is under threat – and the election season can make them especially sensitive.

In an article for the U.S. magazine The Atlantic, Indian journalist Vaibhav Vats argued that the recent anti-Muslim mayhem in the north Indian Indian city of Gurugram (which was sparked by the disruption of a Hindu religious procession in neighboring Nuh) could be traced to two particular upsets suffered by the Modi administration: BJP’s electoral defeat in Karnataka and the formation of the opposition Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance or INDIA.

“These twin events felt like political earthquakes,” wrote Vats. “They cast doubt on what until recently had seemed certain: Modi’s reelection as prime minister for a third consecutive term in 2024. And as Modi and his party have begun to feel politically threatened, they have let loose the foot soldiers of the Hindu right upon India’s minorities.” ◉

Sonia Sarkar is an independent journalist who writes on South and Southeast Asia.