|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

E

very time a national election draws near in Bangladesh, the country’s liberal and secular ethos, upon which it was established after a bloody war in 1971, is challenged. This year is no exception. As this Muslim-majority South Asian nation of 164 million people prepares to go to polls scheduled early next year, attacks on its ethnic and religious minorities have seemed to spike. And just like before, Hindus, who at 12 million make up almost eight percent of the population, are the top targets.

Last February, 14 idols at 12 Hindu temples in Thakurgaon in northwestern Bangladesh were allegedly vandalized in one single night. In the same month, over 1,200 Telugu-speaking Hindus were evicted from a colony in the capital, Dhaka, by the authorities over charges of illegal occupation.

A few weeks after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina announced the holding of the next general election in January 2024, Tarique Rahman, the joint convenor of Bangladesh Gono Odhikar Parishad, a group backed by the Islamist political party Jamaat-e-Islami, announced in a Facebook video that scriptures of the Hindu religion are “porn texts.”

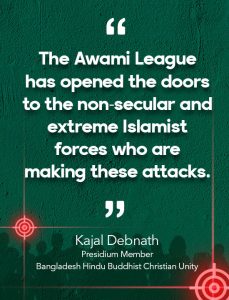

Speaking to Asia Democracy Chronicles (ADC) about such attacks targeting Hindus in particular, Kajal Debnath, presidium member of the secular Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council, cited a popular local saying: “Election inevitably means torture.”

“There is a rise of attacks on minorities, hate speech based on religion, sexual harassment of Hindu women to disrupt peace and stability ahead of the national elections to challenge the secular fabric of the country,” Debnath said. “It’s been a trend in Bangladesh since 2001.”

At that time, widescale violence largely against Hindus had broken out following the election victory of the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), which counts Jamaat-e-Islami among its allies. In 2014, minorities also came under attack during and after the elections that were boycotted by opposition parties that by then were led by the BNP.

It was the same story during the 2018 polls, with even U.N. human-rights experts noting in the run-up to those elections that “religious minorities, especially Hindus, fear renewed targeting.

“Unfortunately,” the experts added, “these fears have a strong basis.”

The daughter also rises, but …

Bangladesh’s religious minorities – which aside from Hindus include Buddhists and Christians (mostly Roman Catholics), as well as other faiths – have endured discrimination and violent attacks even during non-election time, of course. The attacks have included murders, sexual assaults, and the destruction of private property and religious artifacts and structures.

According to the rights group Ain o Salish Kendra, Bangladesh’s Hindu community suffered nearly 3,700 attacks between January 2013 and September 2021 alone.

Like other minorities, Bangladeshi Hindus traditionally support the Awami League, which has a secular platform. Awami League’s standard bearer for the last three decades, Sheikh Hasina, is the daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, the main force behind the creation of a “secular” Bangladesh.

Observers have cited as reasons for the attacks on Hindus in particular the rise of Islamist extremism in Bangladesh, attacks on Muslims in neighboring Hindu-dominated India, and even land-grabbing attempts. At least one local journalist attributed Bangladesh’s minorities-targeted election violence to an “anti-Awami League mindset.”

Rana Dasgupta, a Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council member, pointed out to ADC, however: “Despite being a secular prime minister, the question is why has (Sheikh Hasina) not been able to stop the Islamist radicals in the country? Why is there a need for her to appease Islamist forces when she has been in power for three consecutive terms?”

Hasina became Bangladesh’s premier in 1996, holding the post until 2001. She returned to power in 2009, after which the Awami League won three consecutive elections, resulting in her remaining as prime minister up to this day.

But the Bangladesh that Sheikh Hasina came to lead was no longer the same one that her father had helped fashion, even as early as her first term.

Bangladesh, which shares rich literature and culture with India’s Bengali-dominated state of West Bengal, used to be known for its extremely progressive outlook regarding religion and gender. Bengalis made an identity by their culture, not by religion.

In 1975, however, Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujib, the first president and founder of Bangladesh, was assassinated. Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman took charge of the country, and amended its secular constitution by promoting Islamist ideology by passing several proclamation orders between 1975 and 1979. One of them was the insertion of religious references, such as “Bismillah-Ar-Rahman-Ar-Rahim (in the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful)” in the preamble to the constitution. References to secularism in the constitution were replaced by “absolute trust and faith in Almighty Allah.”

In 1988, then President Hussain Mohammad Ershad amended the constitution further to make Islam the state religion.

Dasgupta himself said that these amendments alienated the secular Bengali nationalists, who either directly fought the liberation war or supported the war, irrespective of their religion.

“Gradually, religion started becoming the main part of a Bangladeshi’s identity,” Dasgupta said. “Islamists, who came to the forefront in the country’s political, cultural and social fabric, remain active till today.”

Prominent human rights defender Sarwar Ali meanwhile said that the exposure of Bangladeshis toward the more radical form of Islam — largely Wahhabism — is one of the reasons behind the rise of Islamist extremism in the country. He traced this to the huge influence of Saudi Arabia’s conservative Islam on the lives of ordinary Bangladeshis after thousands upon thousands of them began going to the Middle East to work.

“Historically, Bangladesh has believed in Sufism,” said Ali. “It never practiced an intolerant Islam as it’s (doing) today.”

Questionable concessions

In 2011, the Hasina-led government restored to the constitution all the lost principles, including secularism. But it retained Islam as the state religion, and the words “Bismillah-Ar-Rahman-Ar-Rahim” in the charter’s preamble, arguing that these reflected the “beliefs” of the majority.

A secular activist who declined to be named said that religion-based identity has been progressing toward taking center stage in Bangladesh, leading politicians to appease those who have taken this stance.

Other observers said that such politicians have included Sheikh Hasina, whose “proximity” to Islamists in the last several years has not escaped attention.

In 2019, days before the national election, Hasina shared a dais with Maulana Shah Ahmad Shafi, chief of the Islamist group Hefajote Islam, who bestowed on her an honorific: Qawmi Janani or mother of the qaum (in this case, the Islamic collective as well as the nation).

In 2018, Hasina announced that the government will recognize the Dawra-e-Hadith, the highest qaumi degree, as a postgraduate degree in Islamic Studies and Arabic.

In 2017, the Hasina-led government introduced religious education in government schools, edited out poems and stories that Islamists deemed “atheistic,” and, most recently, recognized the Qawmi Madrasa degrees. The same year, Hasina also gave in to Hefajote Islam’s demand to remove the Statue of Justice — a blindfolded woman dressed in a sari — outside the Supreme Court building, because having such a figure was idolatry and therefore un-Islamic.

“Awami League wants to get the ‘majority’ of the majority votes,” said Debnath. “It is more concerned about concentrating the votes of the majority- so the party appeases the Islamists. The party wants to decentralize these Islamist forces so that they don’t unite and oppose it politically.”

Yet, Debnath said that of the 300 parliamentary seats, Hindu votes are the deciding factor for Awami League in 120 to 130 seats. He said that the party will be in a perilous state if it doesn’t get these votes.

Hindus and other religious minorities, though, have noticed that Awami League politicians had instigated some of the attacks on them. Just last March, a court sentenced a local Awami League politician to four years in prison over the 2016 torching of a Hindu temple in communal violence in Nasirnagar in Chittagong, on the country’s southeastern coast.

“Awami League has opened the doors to the non-secular and extreme Islamist forces who are making these attacks,” said Debnath. “Although the party claims that these people are not original members and intruded into the party, the truth is that (it) has not stopped these people from making such attacks.”

A diminished BNP?

In the past, many observers had been quick to point to the opposition BNP, along with Jamaat-e-Islami, as being behind many attacks on Hindus. Founded by Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman, and now run by his wife Khaleda Zia, BNP has been alleged by secular forces to be pandering to religious extremists. But Hasina has put many of its politicians in jail, and a few including Khaleda Zia, who was imprisoned over graft charges, are now confined to home with no active political life.

For sure, though, the jailing of several BNP stalwarts itself had triggered violent attacks against Hindus and other minorities. Interestingly, BNP politicians recently demanded an impartial investigation into the attacks on Hindus, ahead of the election, in an apparent attempt to pander to the Hindu voters.

Author Mofidul Hoque, who is also one of the founding trustees of the Bangladesh Liberation War Museum, said that after Mujibur Rahman’s murder, it wasn’t just a change of regime that took place, but also a change of the basic values on which Bangladesh stood.

Yet while Hoque conceded that communalism in any country rises with the endorsement of the state, he argued that the government is trying to confront obscurantism, as well as communal hatred and discourse.

“The struggle is to confront them in a more vigorous manner,” he said, adding that he remained hopeful.

“The emergence of Bangladesh itself,” he said, “is a negation of two nations’ theory: the ideology of religious nationalism. We have history on our side, and therefore the battle against Islamist radicals will continue.” ◉