Iinitially set out to write this article a year ago, at the height of the violence against Asian Americans in the United States. At that time, I had just heard about the Atlanta spa shootings where eight people’s lives were recklessly taken by a 22-year-old Caucasian man. Six of those who were killed were Asian women. The Atlanta shootings shook the Asian American community, as after a string of daily violent crimes against Asian Americans this was the most grotesque to date and made national headlines.

Most times, stories about violence against people of color bypass mass media, but the social media accounts of the Asian American journalists I follow provide a daily update of violent hate crimes against Asian Americans nationwide. The Atlanta shootings sent shockwaves across the community; we thought we must have hit the peak. Unfortunately, day after day the violence continued, especially against women and the elderly.

In fact, only days after the Atlanta shootings, a Filipino American woman walking in New York was knocked to the ground and kicked multiple times in the stomach. The perpetrator did these while yelling, “You don’t belong here!” I lost all hope in humanity a second time when I found out that there were at least two men inside a building watching the woman struggle to get up — but they closed the front door of the building instead of helping her.

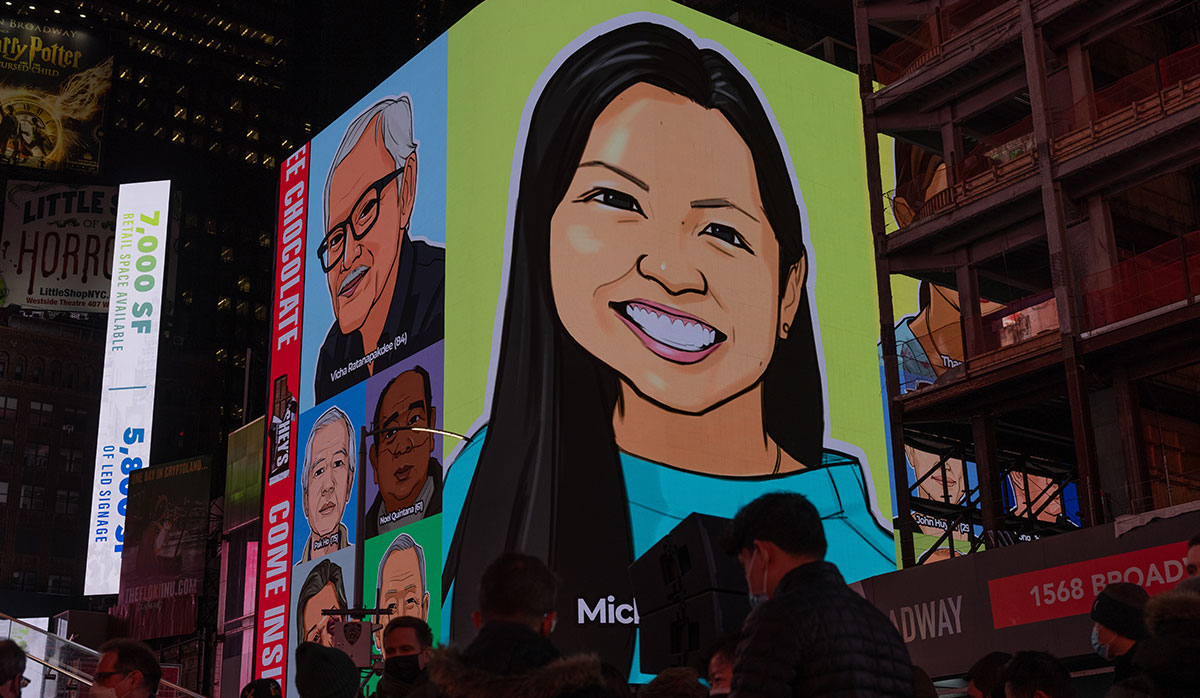

An image of Michelle Alyssa Go and other Asian American and Pacific Islanders — all killed in hate crimes — appear on a billboard in Times Square in New York City. Go and the others portrayed here were honored in a candlelight vigil in January 2022.

A 65-year-old Filipino American being beaten senseless in broad daylight in New York City. Sixty-five years old … that is the age of both my parents living in Chicago. That could have been my mother or father.

At that point, I broke down. I didn’t know how to process what was happening in the country I called home and loved. What made me feel more frustrated was that I was living abroad at the time and I felt there was so little I could do. I felt helpless. “You don’t belong here…” — words that I am all too familiar with as an Asian American. Amid the pandemic, instead of telling my parents to be careful of the raging coronavirus, I tell them to be aware of attackers and to go to places that have many people.

Trying to process what was happening, I dropped the idea of writing this article for a while. But when I picked it up again several months later, I was sad to note that nothing had changed.

In fact, I saw that it was getting worse. Just before I thought of returning to this piece, Michelle Alyssa Go, a 40-year-old finance manager, was waiting on the platform of a New York City train station when a man pushed her in front of an oncoming train. A couple of days later, digital music senior creative producer Christina Yuna Lee, 35, was stabbed to death by a man who had followed her to her Chinatown apartment. These attacks on Asian Americans seemed too targeted to be labeled as mere coincidence.

And these two cases hit closer to home, as I directly fit the demographic of these women. I am Michelle and Christina. I broke down again.

Rising and rising

In 2020, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes had increased 150 percent from the 2019 figure. But the comparable statistic in 2021 shows an even bigger leap of 339 percent from the previous year.

It has to be said, however, that while there has been a significant increase in hate crimes against Asian Americans, African Americans remain the most targeted racial group for such crimes. Sadly, this culture of hate against the vulnerable has been on the rise in the United States.

More often than not, a violent crime that is racially motivated is not tried as a hate crime. Appalling as it is, the Atlanta shootings were not declared hate crimes by the authorities until the District Attorney in Fulton County declared them so. Michelle Go’s death was not declared a hate crime; neither was Christina Yuna Lee’s.

In the African American community, the most targeted group when it comes to hate crimes, this is far too much of a familiar story. In 2012, an unarmed 17-year-old student, Trayvon Martin, was shot and killed by neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman, who reported a suspicious man in the gated community in Florida and then used unnecessary excessive force. It’s hard not to believe that this was racially motivated — to spot an African American male and to automatically think he was up to no good and that the only way to stop this “suspicious“ man was to shoot him.

In reality, the teenager was visiting his family in the gated community and had been there several times before. This case was also not prosecuted as a hate crime, and Zimmerman eventually was acquitted of the murder.

In 2020, almost 10 years after Martin’s death, I glimpsed a ray of change when three Caucasian men were handed life sentences for hunting down and murdering an African American man, Ahmaud Arbery, while he was on his daily jog in broad daylight in a suburb in Georgia. On Feb. 22, 2022, nearly two years to the day Arbery was killed, a jury found the three men guilty of federal hate crimes, setting a precedent for such crimes.

Wanda Cooper-Jones, mother of Ahmaud Arbery, speaking outside the Glynn County Courthouse in Brunswick, Georgia in the U.S. in November 2021. Three months later — and nearly two years after her son’s death — the three men who killed her son were found guilty of federal hate crimes.

And yet, this case came to light only after Arbery’s story went viral, and the public pressured relevant authorities for justice. Before then, the three men — a father and son and their neighbor — were roaming around free. It is terrifying to think about the many Ahmaud Arberys that exist that we just do not know of. Of how corrupt the system is that it took more than two months before Arbery’s killers were arrested.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, a hate crime at the federal level is a crime motivated by bias against a race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability. For the first time in 12 years, the Federal Investigation Bureau (FBI) said recently, the number of hate crimes has skyrocketed.

I believe it. I see daily reports of violence due to xenophobia, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, anti-LGBTIQ, just to name a few.

Yet the report “Hate Crimes Reported by Victims and Police,” released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics way back in 2006 says that the number of hate crimes in the United States is actually 15 times higher than the FBI data. The report indicates that this is because FBI statistics are based on voluntary reports submitted by police. In addition, there is an underlying fear among people of color that reporting such incidents to the authorities would only bring about negative fear of repercussions.

Speaking up, demanding to be heard

The truth, though, is that even if they are reported, hate crimes are hard to prosecute. To prove an incident was a hate crime, we must confirm that the motive was solely due to the perpetrator’s bias against something that he or she thought the victim represented or was part of. But it is difficult to assess and determine what went on inside a criminal mind and present that as proof in court.

This is why there is stricter scrutiny with hate crimes; the burden of proof lies heavily on circumstantial evidence. This difficulty in proving hate crimes directly relates to why so few of these are reported.

Yet despite the low probability of obtaining justice through hate-crime prosecution, we must continue to highlight these violent crimes against people of color as hate crimes and demand justice for such. Through speaking up and raising awareness about these hate crimes, we will start to engage the masses to be more cognizant of violence arising from bias and the reality of widespread hate crime in the United States.

Just recently, there was yet another Filipino woman beaten up in New York. The 67-year-old was punched 125 times in the head, stomped on seven times, and spat on twice.

The aggressor was a 42-year-old African American man who has been described as a “neighbor” in reports. As he beat her, he yelled “Asian b****!” He was arrested and has been charged with attempted murder and assault in the second degree involving a victim who is at least 65 years old; each count is charged as a hate crime.

The recent significant hate-crime prosecution in the Ahmaud Arbery case and the string of Asian violence incidents now being officially seen as hate crimes are steps forward to changing the culture of shying away from hate-crime prosecution and being more conscious of the systemic racism in the U.S. criminal justice system.

Although I cannot be there physically, I hope that sharing this piece with the international community will contribute to the activism for an increased awareness of the plight of vulnerable groups, which in turn could help stop Asian hate and systemic racism in the land of the free. ●

Soo Suh is the Senior Program Manager at the Asia Democracy Network, which seeks to promote and defend democracy in the region. Previously, she was a research fellow at the Korea Human Rights Foundation, mainly implementing and managing its Human Rights Monitor project.