As his family of five stood waiting with scores of other Afghans at the Chaman border crossing, Fazl-e-Rabbi made a mental rundown of the things they had that would help them prove they should be let into Pakistan: medicine receipts, prescriptions, and visit information from Pakistani doctors, the addresses and contact information of relatives from Peshawar. The guards were not letting everyone through, and Rabbi was running out of options.

Then it was their turn. Recalls Rabbi: “It just happened for us that while the officers were refusing so many people, they let us pass through the gates.”

In some ways, it was actually a homecoming for Rabbi, and his family, which included one of his brothers. In 1980, he and his siblings, along with their parents, had fled the Afghan War and sought refuge in Pakistan. He and his siblings grew up in Peshawar. Rabbi was able to graduate from university in Pakistan and met and married his wife there.

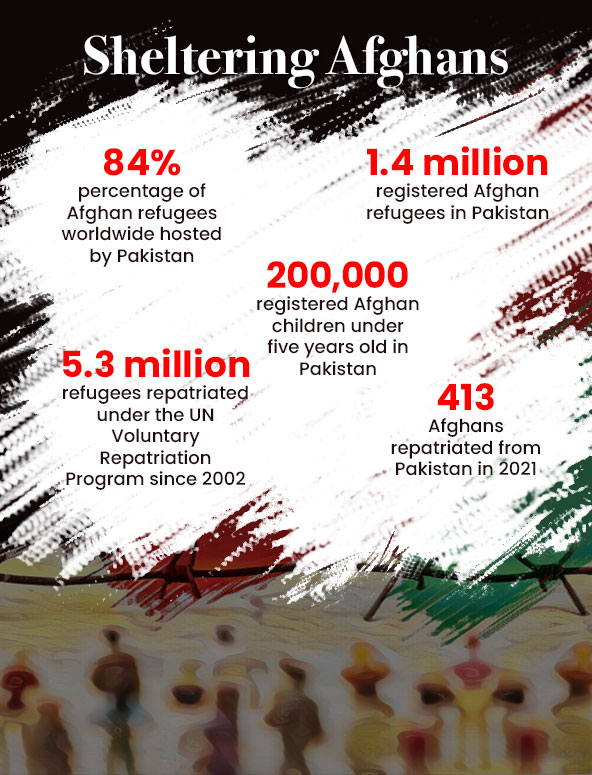

Officially, there are 1.4 million registered Afghan refugees in Pakistan. Rabbi and his family used to be part of that statistic and lived a relatively ordinary life in their adopted country. But things began to change in 2015 when Pakistan, with facilitation from United Nations Higher Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), started what was supposed to be the voluntary repatriation process of over 50,000 Afghan refugees.

Border guards conduct body searches on Afghans entering Pakistan via the Chaman border. It’s a scene that played out on repeat for years. These days, it’s the reverse as Pakistan sends the Afghans back home.

As Rabbi recalls it, police constables, accompanied by women colleagues, would visit their house, harass them, insisting they leave the country. He says, “When we would go out to run errands, they would stop us in our tracks and ask questions despite us having proof of registration cards.”

In October 2016, about 15 families from their neighborhood in Peshawar, including Rabbi’s and his in-laws, made their way back to the eastern Afghan city of Jalalabad.

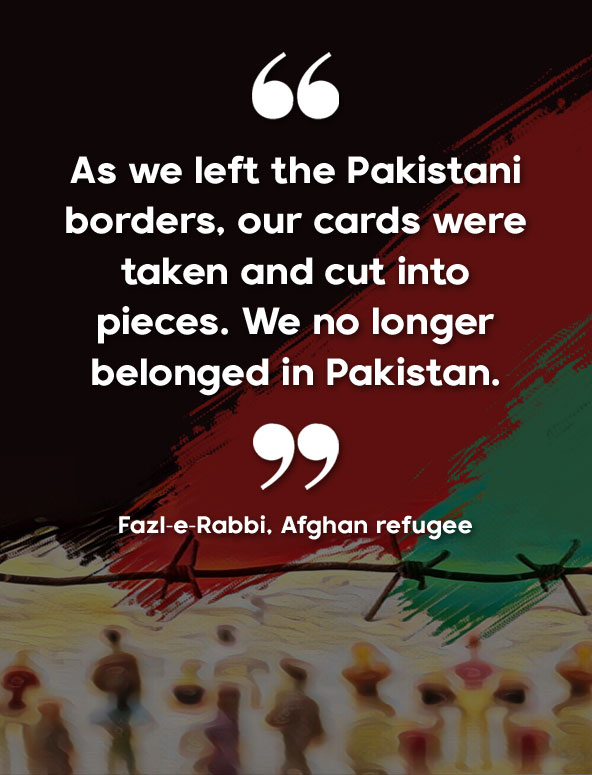

“As we left the Pakistani borders, our cards were taken and cut into pieces,” Rabbi says. “We no longer belonged in Pakistan.”

The UNHCR says that since 2002, nearly 5.3 million Afghan refugees have returned to Afghanistan under the UN agency’s Voluntary Repatriation Program. Even as late as the third quarter of 2021, when the Taliban had already retaken control of the country, as many as 118 Afghan refugees returned to their homeland under the program. According to the UNCHR, a total of 1,266 Afghans were repatriated in 2021, including 413 from Pakistan.

For sure, though, Afghans fleeing their country have been in the hundreds of thousands in the last several months. Most have gone to nearby Iran and Pakistan, which host 85 percent of the Afghan refugee population worldwide. In Pakistan, it has been estimated that the number of unregistered Afghan refugees now matches that of the registered ones.

Escaping forced recruitment

Rabbi says that it was actually a recruitment movement during the Afghan War that pushed their parents to move the entire brood elsewhere. In 1979, the then Soviet Union declared its support for the Afghan communist government, and its troops entered the country to fight the anti-communist mujahideen.

“Men from the government coalition would come to school to take away boys to fight with the mujahideen,” says Rabbi, now in his 50s. “I remember I was in Grade 4 and the school bell had rung and we were prepping to go home when soldiers entered my class and started taking the boys with them forcibly.”

But while Rabbi had some luck on his side and escaped being taken away, his father didn’t. He was taken away a few times and much like many Afghan men at the time, he would go into hiding frequently.

“There was one time,” recounts Rabbi, “I remember crying when they were taking him away. I must have been seven at that time and remember being told that he was taken to an ‘army place.’ One of our relatives was in the army and saw my father there. He came over to our house and consoled us, saying that he would bring our father back and that we should not worry. And so he brought him back, but my father knew this wouldn’t be it, and decided to move us to Pakistan.”

The next three decades of Rabbi’s life were spent in Peshawar with weekly trips to Mazaar-i-Sharif, the fourth-largest city in Afghanistan, where they still had a jewelry-making business. After completing his education, Rabbi also started working as a tourist guide. In 1999, he became the guide of a Canadian couple who were on a 10-day trip in Pakistan’s Swat Valley. He became good friends with the couple, especially with the husband, and their relationship has lasted until today.

Fast forward to post-9/11, when the U.S. “War on Terror“ was evolving into efforts of nation-building in Afghanistan. Rabbi’s Canadian friend told him about an opportunity with a U.S. non-profit involved in childhood enrichment programs. Rabbi then began working on projects that required him to cross the border into Afghanistan. But he would usually return to Pakistan in a week.

“We didn’t think of going back (to Afghanistan) because it was never safe,” says Rabbi. “Up until my brother and I had completed our education, we didn’t believe there was much in Afghanistan to find a good environment to work. Then in the late ‘90s Taliban took over and it made even less sense to go back to our roots.”

Rabbi didn’t directly live under Taliban rule in the late ‘90s but knew about the strict governance there. He recalled an incident when one of his friends, Abdul Hajan, went to Kabul accompanied by another friend. From Torkham to Kabul, the two friends took a bumpy, difficult ride to Kabul and met with Rabbi’s father.

“What are you doing here, Abdul Hajan?” Rabbi’s father asked him.

“We are here just for a trip.” Abdul Hajan replied, lightly.

“You think Kabul is a place for a fun trip?” Rabbi’s father said angrily. “Why did you have to come?”

People gather to protest against the Taliban in Vancouver, Canada. Some Afghan refugees hope for opportunities to relocate to other countries as their nation’s next-door neighbor shuns them.

The Taliban’s return

In the days Abdul Hajan was visiting Afghanistan, the Taliban were imposing draconian rules under the garb of Islamic law. Music, photography, film, secular and women’s education (with only some exceptions) were banned. As Abdul Hajan and his friend moved around in the city, they were stopped by Taliban men. The friend had a long beard and the Taliban took an interest in him. “Your beard is very sharp!” they remarked, scanning him from top to bottom. They then proceeded to ask them questions about their compulsory five-times-a-day prayer.

“We knew they were strict,” Rabbi says. “Especially my children, who are all Pakistan-born and have only heard about horrible things about them.”

And when he heard that the Taliban were already in Kabul on Aug. 15, 2021, Rabbi knew he and his family had to leave. Like many other Afghans who had worked with the U.S. forces and NGOs, Rabbi felt fear that the Taliban would go look for him.

“I was at the Hamid Karzai International Airport,” he says, recounting how it was being with the thousands of people trying to leave Afghanistan via flights arranged by the departing allied forces. “The US and Afghan army were there. The rush of people was maddening.”

He holds up a finger, its nail pitch black. “The Afghan soldiers wanted space to move toward the aircraft, but people were blocking it,” says Rabbi. “They drew out a stick and started beating people so they could make way for them. I, too, got hit.”

The next morning, Rabbi, along with a friend, went to the airport again. Among scores of troops were documented and undocumented Afghans trying to get on board the remaining aircraft. “I had all the documents and felt in a better position than many others,” says Rabbi. “But from what I could see, there was no way I could get to the front.”

He continues, “If a family of four, by some struggle, did make it through the gates and fought its way through the crowd to the front, not everyone was getting on the aircraft. So families were separating right before my eyes. I thought if I board this and this plane gets to an unknown destination in the Middle East, for example, how would I call or sponsor my family later?”

With these thoughts in mind, he left the airport and headed toward downtown Kabul. His friend happened to glance at his phone; he told Rabbi that there had been an explosion at the airport. “My first reaction was that this must be fake news,” says Rabbi; later it was confirmed that indeed 170 Afghans had lost their lives and dozens were wounded.

Rabbi didn’t think of trying his luck again until his Canadian friend encouraged him to leave Afghanistan immediately, even if that meant taking an uncertain journey to Pakistan with expired passports. “Move your family, cross the border into Pakistan, and we will do something for you,” his friend told him over the phone.

And so on the day when the last soldier of the U.S. army took his exit and the U.S. war in Afghanistan was officially over, Rabbi and his wife and daughters, along with his younger brother, left Jalalabad in the dead of the night, without a word to relatives or neighbors. Their bus reached Kandahar city by midday, with the journey unperturbed by checkpoints or nosy officials asking questions.

“It was like a freeway with no single checkpoint to stop us anywhere,” says Rabbi. “We could see things were not the same.”

From there the family went straight to Spin Boldak, aiming to go through the Chaman border into Pakistan. Rabbi had observed that the border officials were only granting permits to those with valid visa documents, previous refugee cards, or some documentation of prior visit and residency. But each day hordes of people tried their luck anyway.

After spending a few nights in Spin Boldak, the family made it to the border and showed their documents. The official took one look at the family and prescriptions of medicine from a clinic in Peshawar, and let them pass. They crossed the Chaman border and journeyed over 600 kilometers to reach Pakistan’s coastal city of Karachi after a week.

Rabbi’s family has been staying in a small rented room since, but they are not looking to make Pakistan their home. They are planning to seek asylum in Canada with the help of Rabbi’s friend. Yet while Pakistan is no longer as welcoming of Afghan refugees as it was decades ago, it is keeping Rabbi and his family safe for the moment. Says Rabbi, “We are grateful.” ●

Haniya Javed is an independent journalist from Pakistan reporting on human rights, labor, and the environment.