|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

NORTHEAST ASIA

Stepping up pressure on North Korea

Ten years since the U.N. released its damning report on the human rights abuses perpetrated in North Korea, the international community has renewed a now decade-old call to haul the Kim Jong-un regime before the International Criminal Court (ICC) despite the fact that the isolationist nation has never been a member of the high international court.

In a speech before the U.N. on March 20, deputy high commissioner Nada Al-Hashif said that while the “primary responsibility for accountability” for these crimes rests with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea itself … it is imperative that accountability is pursued outside the DPRK.”

Aside from referring these violations to the ICC or pursuing national-level prosecutions outside North Korea, she said non-judicial measures may also be adopted such as reparations and memorials to ensure justice is served for the victims.

Her statement comes as the U.N. marked the 10th year of the publication of its landmark inquiry on North Korea, which revealed widespread and ongoing human rights violations in the East Asian nation, including torture, starvation, executions, and harsh labor conditions for prisoners in detention camps.

Among the human rights abuses flagged by the body included the sentencing and detention of South Korean citizens like Choi Chun-gil, a South Korean missionary who was accused of espionage and then sentenced to life in prison in 2015, just as the U.N. opened a human rights office for North Korean in Seoul.

On March 21, Choi’s son, Jin-young, called on the international community to amplify their calls for the DPRK to release his father and the five other South Koreans who have been detained in the north for years while their exact whereabouts remain unknown.

The unification ministry in Seoul recently created a symbol comprising an image of three forget-me-nots of South Koreans detained in the north.

The last time the South Korean government negotiated the issue of detainees with North Korea was during the April 2018 inter-Korean summit at Panmunjom, a village near the North-South Korea border.

SOUTHEAST ASIA

A louder call for ceasefire

After months of quietly mobilizing and supporting civilian-led aid for the Israel-Gaza conflict, Singapore has turned more assertive with its calls for a ceasefire and sent its first humanitarian airdrop into the embattled enclave.

On March 20, Singapore finished dropping off crates of food and other essential items just as its foreign minister, Vivian Balakrishnan, met with Israel leaders to convey the city-state government’s message that that their actions in Gaza “have gone too far” and that there was a need for an immediate ceasefire so more aid could come into the region.

“If that can be achieved, then a whole flood of humanitarian assistance can reach the civilians in Gaza, and the best way of doing this would be through a ground-based route,” Balakrishnan told reporters.

Singapore has long supported a two-state solution in the Gaza Strip, where millions of Palestinians are subjected to what rights groups call virtual “apartheid.” But it has also mostly steered free from debates, banning rallies and integrating the Israel-Palestine conflict in their curriculum as a “lesson on safeguarding cohesion in a multiracial country.”

As such, experts like Chong Ja Ian, a political scientist from the National University of Singapore, believe that Balakrishnan’s comments signaled a “subtle shift” that the country was becoming “more vocal on the excessiveness of Israel’s behavior, while also noting Israel’s need for self defense.”

He added that the city-state might also be trying to signal its Muslim-majority neighbors, Malaysia and Indonesia, who are also the most vocal for Palestine.

Of all Southeast Asian countries, Singapore is deemed to have the closest relationship to Israel, as the Israeli Defense Forces were the ones who helped build up the Singaporean Armed Forces.

Nevertheless, the IDF’s relentless assault on the strip, which has led to over 25,000 Palestinians killed, has since soured most of Southeast Asia – historically a regional bloc that tries to avoid taking sides in a conflict, says Joshua Kurlantzick, Council of Foreign Relations Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia.

Singapore’s immediate neighbor, Malaysia, had imposed a ban last December on all Israel-owned and flagged ships from docking at its ports as a sanction against the Middle Eastern country for the “ongoing massacre and continuous cruelty against the Palestinian people.” Indonesia joined Malaysia in calling on the International Court of Justice to deliver an advisory opinion to stop Israel’s “unlawful occupation” of the Gaza Strip.

SOUTH ASIA

Calling out Modi’s excesses

Amid wide perceptions that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is tightening his grip on the opposition as this year’s general election looms, supporters of the opposition took to the streets to call out his administration for abusing its authority to target and undermine political rivals.

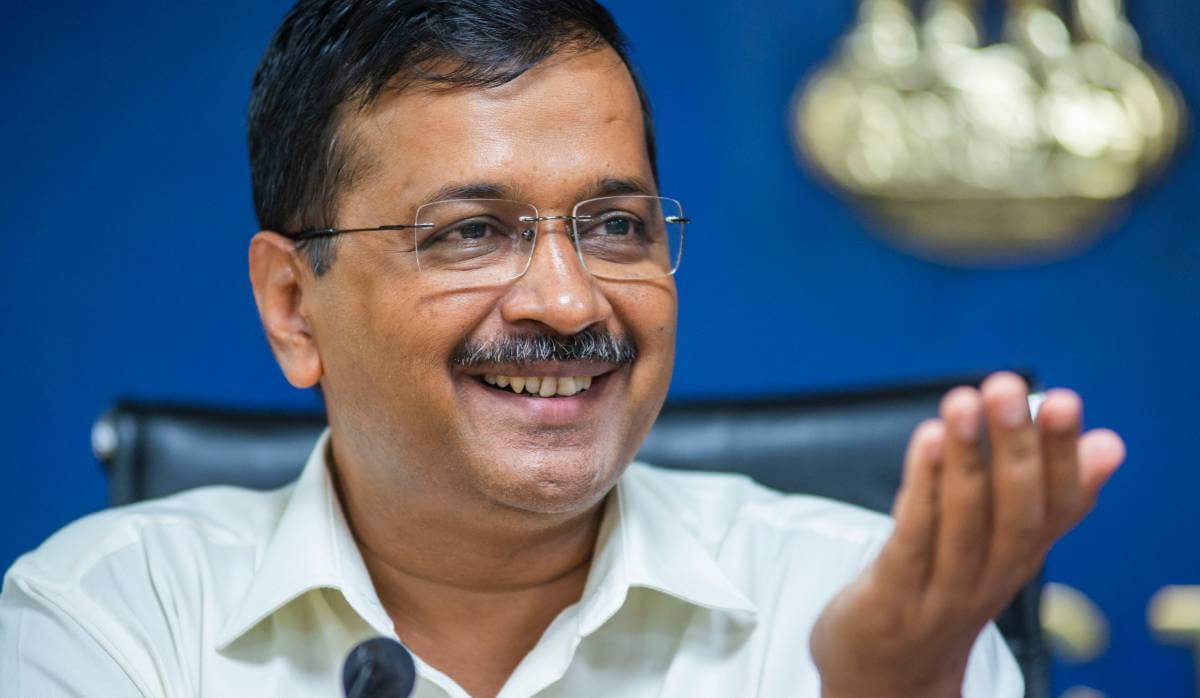

On March 22, protests exploded in the capital New Delhi after chief minister and prominent anti-corruption figure Arvind Kejriwal was arrested over allegations that he accepted 1 billion rupees (US$12 million) in bribes from liquor contractors two years ago.

Kejriwal’s supporters – including leaders of the political bloc INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance) formed by at least 24 opposition parties to mount a challenge to Modi – denounced his arrest as part of a broader government crackdown orchestrated by Modi’s administration ahead of the April 19 national elections.

“A scared dictator wants to create a dead democracy,” Congress leader Rahul Gandhi said, while Mamata Banerjee of the Trinamool Congress Party called it “a blatant assault on democracy.”

Tamil Nadu chief minister M.K. Stalin, a fellow member of the opposition bloc, said Kejriwal’s arrest “smack(ed) of a desperate witch-hunt.” It’s also seen as part of a wider crackdown on the opposition, which is challenging the ruling Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the upcoming Lok Sabha (parliamentary) elections.

Last year, Rahul Gandhi, the most prominent member of the opposition Congress, was convicted of defamation charges brought by a member of the ruling BJP, leading to a two-year prison sentence that disqualified him from parliament before a court suspended the verdict.

Meanwhile, Congress – once a towering party in the country – saw its bank accounts frozen last week after the Delhi High Court dismissed its petition challenging the income tax department’s reassessment proceedings.

Last January, authorities also arrested former Jharkhand chief minister Hemant Soren for allegedly facilitating an illegal land sale.

India has lagged behind in all major indices that measure democracy – it ranked only as “partly free” in Freedom House’s 2024 Freedom in the World Report; and 41st (“flawed democracy”) out of 167 countries and territories covered in the 2023 Democracy Index of the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“(T)he modality of India’s democratic decline reveals how democracies die today … it moves through the fully legal harassment of the opposition, intimidation of media, and centralization of executive power,” author Maya Tudor says in an article she wrote in the Journal of Democracy.

Modi, who downplays “Western” indices of democracy, recently tapped a major Indian think tank to develop a “homegrown democracy ratings index” to help it counter its sliding rankings.

GLOBAL / REGIONAL

Another call to abolish the death penalty

The year 2023 saw a record number of at least 467 people executed for drug-related crimes, according to a new report by Harm Reduction International (HRI) that renewed its calls to abolish the death penalty for all cases.

In its latest Global Overview 2023 report published on March 19, the group said that the number not only represented a shocking 44 percent increase compared to 2022, but that the true number was likely higher, especially considering the difficulty in obtaining accurate data from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and North Korea.

Minimum number of drug-related executions, 2014-2023

Source: Harm Reduction International

HRI said they were only able to confirm the number of executions from China, Iran, Kuwait and Singapore. “Most notably, no accurate figure can be provided for China, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia and Thailand, (which are) believed to regularly impose a significant number of death sentences for drug offenses.”

International law prohibits the death penalty for anything less than the “most serious” crimes, and drug offenses do not meet this threshold according to the United Nations.

Despite this, some countries continue this practice. Singapore, for instance, drew criticism after resuming executions in 2022 following a brief respite because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This, while Malaysia observed an official moratorium on executions starting in 2018 and repealed the mandatory death penalty including for drug-related offenses.

Rights groups like Amnesty International unconditionally oppose the death penalty in all cases, calling it the “ultimate, irrevocable punishment (where) the risk of executing an innocent person can never be eliminated.” Moreover, it has not been proven to deter crime even in countries where it is being implemented.

In cases of drug offenses – which constitute the majority of death row cases in Southeast Asia – groups like Eurasian Harm Reduction Association advocate instead for harm reduction programs, drug addiction treatments, employment programs and access to education.