|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

he schools are open once more and residents of Bangladeshi districts bordering Myanmar no longer feel they have to seek safer places each night. But many are wary about what can happen next as fighting rages on across the border, and despite assurances from Bangladeshi authorities that they are on top of the situation.

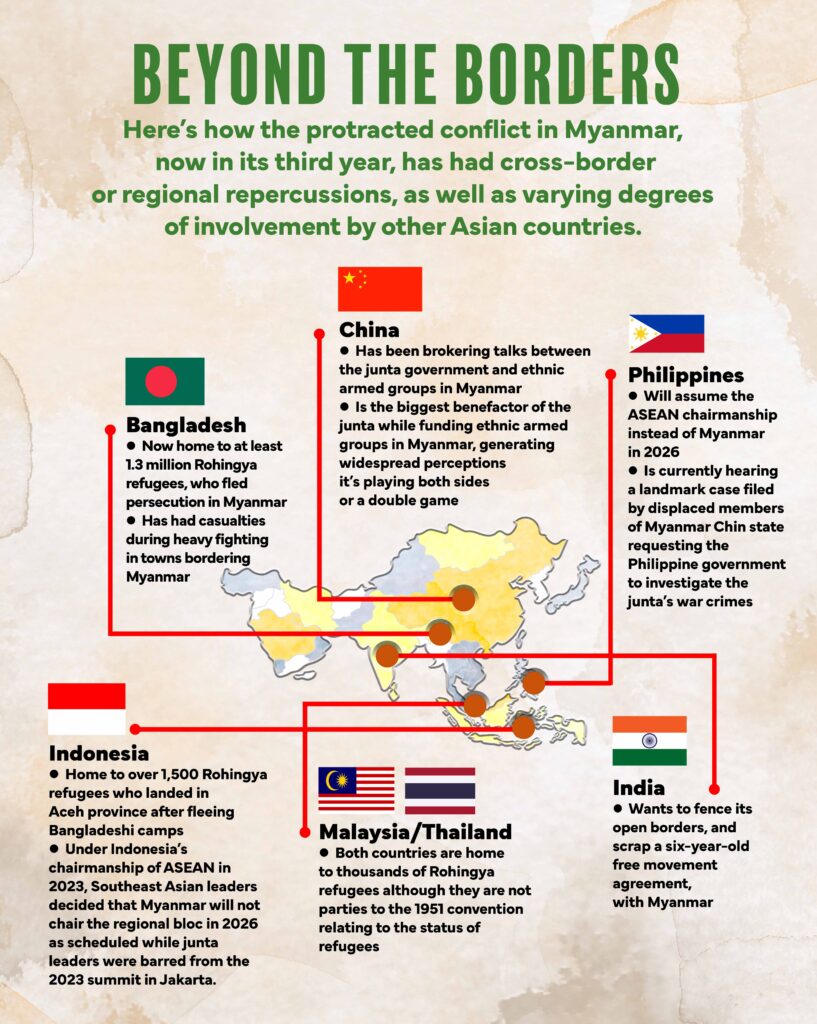

Myanmar shares land borders with China, India, Laos, Thailand, and Bangladesh. The 271-km border it shares with Bangladesh is far shorter than what it has with China, India, and Thailand. In the last several months, however, fighting in the Chin and Rakhine states — which are just next door to Chattogram Division in Bangladesh — has been among the most intense.

Since late October 2023, armed clashes have escalated in Myanmar’s border areas as three armed ethnic groups — the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), Arakan Army (AA), and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) — joined forces to fight against the military junta. Known as the Three Brotherhood Alliance, these ethnic armies have been making significant headway since, along with other armed groups that are as determined as they are to topple the country’s military rulers.

But that determination has meant fierce clashes with the Myanmar military known as the Tatmadaw. Gunfire and bomb blasts could be heard even in the Bandarban and Cox’s Bazar Districts of Chattogram in southeast Bangladesh. Then early last February, bullets and mortar shells fired from Myanmar sailed across the border and into Bangladeshi territory. Several Bangladeshis were injured while at least two have been confirmed to have died, among them a Rohingya refugee.

Mohammad Ibrahim said that his mother Hosneara Khatun was making lunch for their family when a mortar shell landed in the kitchen where she was. Nabi Hussain, a Rohingya refugee who had been hired by the family for the day to do some work, also died in the incident. Several other members of the family were also hit by shrapnel.

Samsul Alam, meanwhile, decided to fetch his married daughter living in the border area after hearing gunfire from Myanmar days earlier. He managed to survive a gunshot wound in the back, which he sustained while he and his daughter were just starting to make their way back to their family’s home.

The temporary closure of schools in Bangladeshi border towns as a result of the fighting in next-door Myanmar may have prevented more casualties. But children and their parents remained fearful for days after, with some families opting to sleep elsewhere each night, and returning only to their border homes during daytime

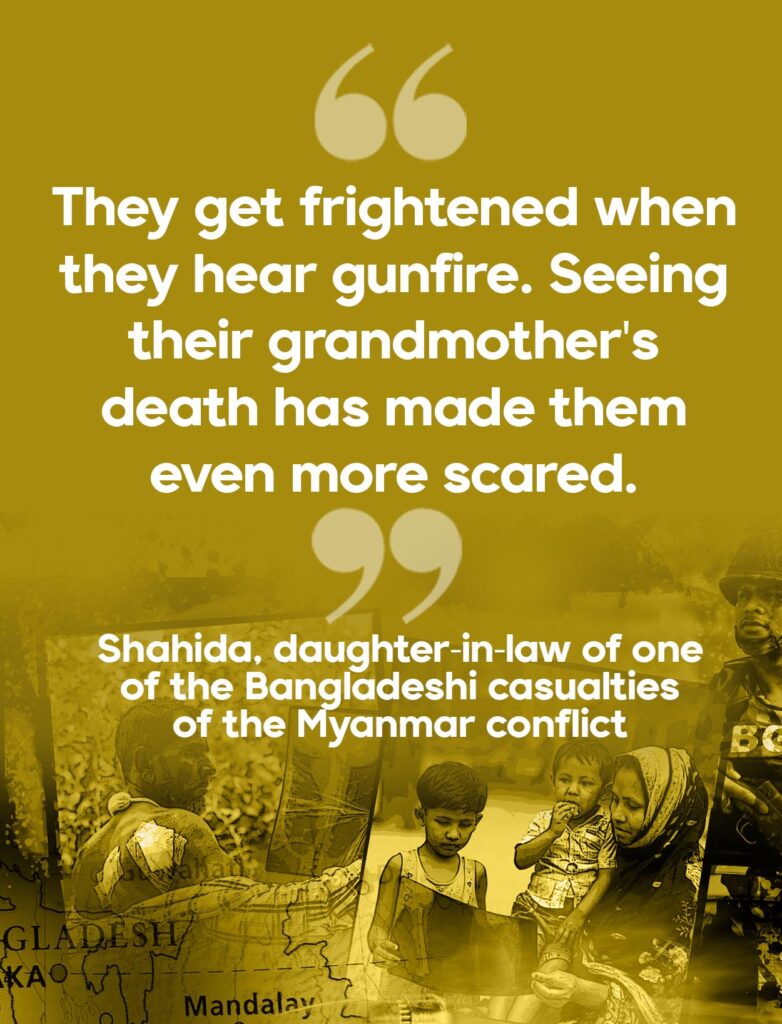

Hosneara’s daughter-in-law Shahida said that her two young children who were injured by pieces of the mortar shell are now too scared to go to their grandparents’ home near the border. “They get frightened when they hear gunfire,” she added. “Seeing their grandmother’s death has made them even more scared. They can’t sleep properly anymore.”

Worry upon worry

The possibility of the border towns being overrun by people from Myanmar fleeing the fighting may also be causing Bangladeshi authorities sleepless nights. According to the authorities, between Feb. 4 and 7, some 330 people, including Myanmar border guards and members of its armed forces called the Tatmadaw, crossed over the border into Bangladesh. Those who had fled with their weapons surrendered these to the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB).

All 330 were placed on a ship and sent back to Myanmar last Feb. 15 after negotiations between Myanmar and Bangladeshi authorities.

Bangladesh is already hosting more than 1.3 million Rohingya, an ethnic minority group that had lived for generations in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. Predominantly Muslim, the Rohingya have been discriminated against by Myanmar’s Buddhist majority for decades.

In 2017, however, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya were forced to leave Rakhine after suffering brutal attacks, primarily from the military. Most crossed the border into Bangladesh, where they have since lived in decrepit refugee camps.

Perennially resource-short Bangladesh has been trying to repatriate them to Myanmar, which has been reluctant to see them return. Today the specter of even more people from Myanmar — whether Rohingya or non-Rohingya — pouring over the border because of the civil war is testing the nerves of Bangladeshi officials.

In a press briefing on Feb. 6, Bangladeshi Foreign Minister Muhammad Hasan Mahmud said that the Myanmar ambassador had been summoned to receive a formal protest over the casualties in Bangladesh caused by Myanmar’s internal conflict, as well as the sudden influx of Myanmar citizens across the border. Most of those who crossed the border were members of the Myanmar Border Guard Police (BGP), while there were also two army personnel and 18 immigration staff.

“In the context when we are working to take back the Rohingyas, such incidents are unintended, unwanted and unacceptable,” said Mahmud at the press briefing. “This we have informed (Myanmar).”

Maj. Gen. Mohammad Ashrafuzzaman Siddiqui, director general of the BGB, said he was present when the ship with the 330 Myanmar citizens on board left the Inani Navy Jet Ghat in Cox’s Bazar and sailed toward Myanmar. He added that Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina had instructed the Bangladesh border security force to control the border situation while “remaining patient and maintaining international relations.”

BGB is on maximum alert and no other people would be allowed to enter from Myanmar, including Rohingya, Siddiqui said. But that may be easier said than done as the Three Brotherhood Alliance and other armed groups continue their campaign to oust the junta, which had grabbed power from an elected government in February 2021.

In Rakhine alone, estimates are that more than 330,000 people have already been displaced by the fighting. In Chin state, which is also next door to Bangladesh’s Chattogram Division, at least 120,000 have been displaced, including some 60,000 who have sought refuge in India’s Mizoram and Manipur states.

Peace dialogue with other stakeholders

At a Feb. 13 forum organized by the media outlet The Daily Star, security and foreign policy experts said Dhaka should start considering talks with other stakeholders in Myanmar, aside from the junta. “We can see clear possibilities of the Arakan Army taking full control of Rakhine State by the year’s end, and the Myanmar military is now in a bad state,” the Daily Star quoted retired Brig. Gen. Sakhawat Hussein as saying in its report on the forum.

“At this stage in time,” Hussein also said, “we should go for diplomacy at track-2, track-3, and track-4 levels. We should engage the National Unity Government and the Arakan Army as well.”

The National Unity Government or NUG is Myanmar’s government in exile that is composed of several parliamentarians elected in the 2020 polls.

Southeast Asian history researcher Altaf Parvez, for his part, pointed out at the forum that Bangladesh should also pay attention to what is happening in Chin State and engage the Chin National Front (CNF). Arguing that the CNF is open to Rohingya repatriation and recognition, he indicated that the group may be helpful in Bangladesh’s efforts to get the refugees back to their homeland.

But that will happen only if the CNF and the rest of the anti-junta groups win in their campaign against the Tatmadaw. In the meantime, Chin State as an active war zone remains a threat to Bangladesh, partly because those fleeing the fighting there could start heading for Chattogram instead of Mizoram and Manipur in India.

There’s a larger worry, however. In a recent opinion piece for Eurasia Review, political observer Md. Himel Rahman noted that Bangladesh itself has an active insurgent group made up of Kuki-Chin nationalists who operate largely in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Rahman said that the Chin State is now “awash with weapons” that could well end up in the hands of these insurgents who could launch more attacks “against the Bangladeshi security forces and civilians.”

In such a scenario, Bangladeshis would be dodging bullets and mortar fire from within their own country. ◉