|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

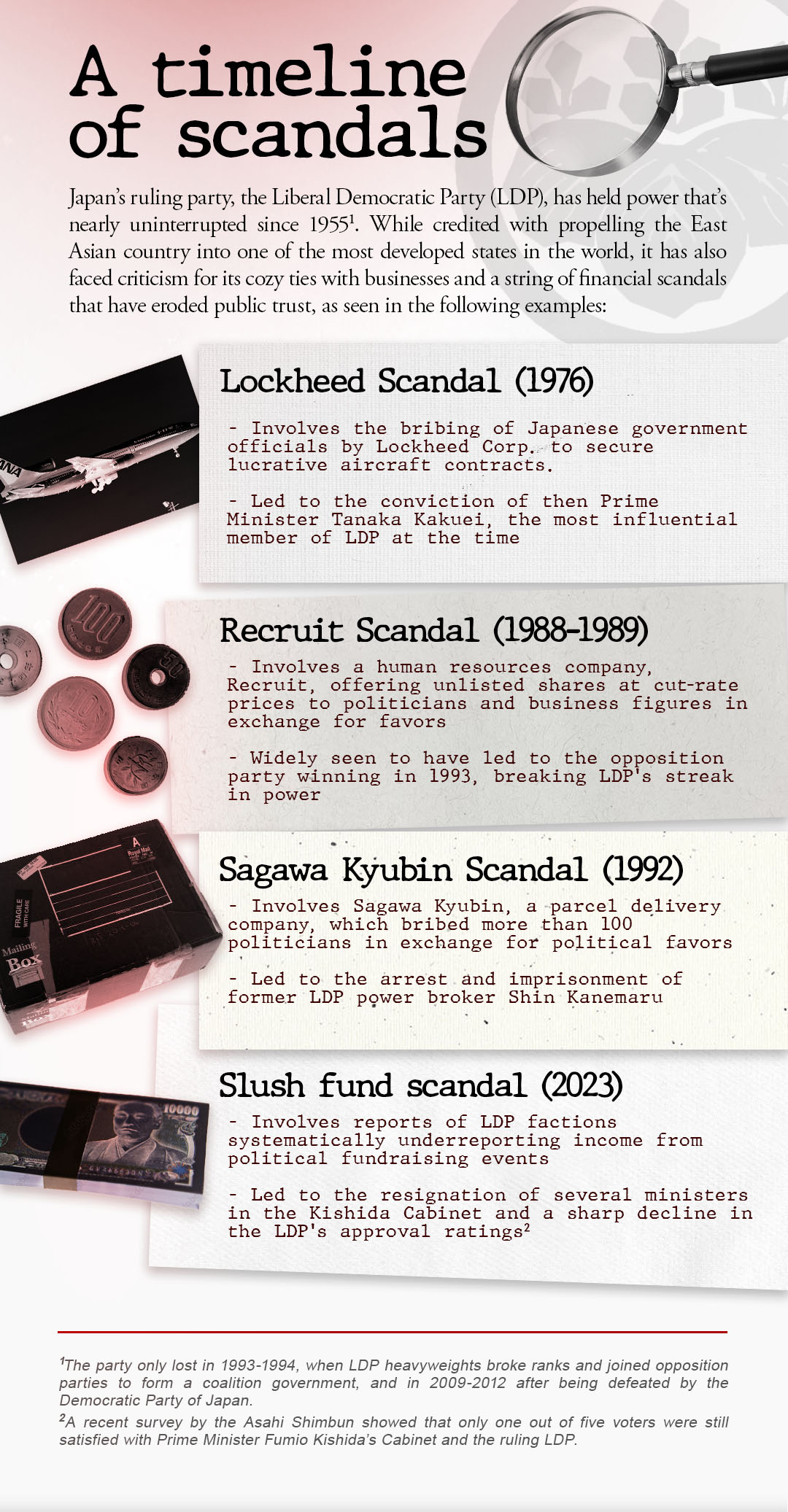

On Feb. 29 Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, representing the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), became his country’s first incumbent premier to appear before a parliamentary ethics panel as yet another consequence of the ruling party’s current slush fund scandal. But neither that nor suggested reforms by the LDP itself may end the practice and others like it due to a deep-rooted culture of factional politics that focuses on personal relationships rather than policies.

The recent money scandal involving the LDP, which has dominated Japanese politics for most of the past 68 years, is not an isolated incident. Despite the record-low approval rating for Prime Minister Kishida’s cabinet, a growing public disengagement from politics suggests the LDP may not only weather this storm but also allow the persistent issue of slush funds to linger.

The LDP slush funds have been around for at least the past several years. But it was only last November that details regarding these became known to the general public, and only after the media reported on an investigation that was triggered by a criminal complaint filed with the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors’ Office.

The LDP slush funds have been around for at least the past several years. But it was only last November that details regarding these became known to the general public, and only after the media reported on an investigation that was triggered by a criminal complaint filed with the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors’ Office.

In November 2022, the Japanese Communist Party’s newspaper, Shimbun Aka Hata, ran an investigative report alleging that five LDP factions, including that of the late former Premier Shinzo Abe, had failed to report some of the revenues generated by their fundraising parties.

According to the report, these factions had left out some JPY 40 million (US$266,000) in their political fund reports from 2018 to 2021.

But no one took real notice of the Aka Hata report – save for Hiroshi Kamiwaki, a professor at Kobe Gakuin University. Kamiwaki, who had been studying political funds for years, reinvestigated the allegations. It was he who last year filed the criminal complaint against the LDP factions.

Since the slush funds became public, the Abe faction – the largest with nearly 100 MPs – has admitted failing to report JPY 670 million (US$4.45 million) over the past five years. The faction led by Prime Minister Kishida also left some JPY 30 million (US$199,000) out of its reports.

Four of LDP’s six factions, including those of Abe and Kishida, have been forced to announce their dissolution after harsh public criticism. Last December, four Cabinet ministers and five deputy ministers resigned, while two MPs were indicted because of the slush-fund allegations.

LDP, however, had gone through worse scandals in the past. That it is in yet another one only shows that Japanese political practices have been slow to change, despite measures that were supposed to revamp the system.

Tainted hands craft reform measures

In the 1970s, then Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka of the LDP and other high-ranking government officials accepted bribes from the U.S. aerospace giant Lockheed over the sale of jetliners. In the 1980s, several LDP politicians were found to have received as bribes unlisted shares in a company affiliated with Recruit, a giant human-resources firm.

In response to a public outcry, the LDP government decided to mandate the publication of political fund reports. After the Recruit scandal, a major electoral reform was also carried out with the introduction of a single-seat constituency system in the House of Representatives to enable a change of government.

But with all these initiated and planned by the party whose members were caught doing wrong, transformational change was probably far from ever taking place.

In Japan, there are no legal restrictions on the amount or use of political funds. This is because the Japanese Constitution ensures freedom of political activity. Instead of direct regulations, Japan has the “Political Funds Control Law,” which aims to enable voters to assess politicians’ actions through public scrutiny.

For all its flaws, the law is better than having none at all. Admittedly, however, its numerous loopholes have inevitably allowed the current scandal to occur. For instance, while political-fund records are supposed to allow public scrutiny, MPs and local assembly members have their revenue and expenditure reports only in hard copy and in PDF form. Moreover, they are required to file these just annually.

With 700 MPs and 32,000 local assembly members submitting these documents, a proper scrutiny of the records can be done only through a searchable database, and preferably one that is constantly updated.

A 1994 amendment to the law had also banned donations to individual politicians. Exempted from this stipulation, however, were political party branches – which are actually represented by individual politicians. Fundraising party tickets for individual politicians can also be purchased by companies.

And while the political-funds reports should contain the names of those who buy party tickets (individuals and companies), along with the amounts they paid, purchases of less than JPY 200,000 (US$1,300) require disclosure only of the amount and not the buyer’s identity.

While legal loopholes present an undeniable issue, the bigger picture reveals a system that incentivizes politicians to prioritize securing support from colleagues and the public alike over crafting effective policies.

This environment has given rise not to slush funds but also factions within political parties. While LDP isn’t unique in this regard, its factions’ distinct characteristic is that each party member can only belong to one such subgroup, fostering a stronger sense of loyalty within.

A common political playbook

The primary driver behind these factions is to secure positions for their members. They obtain support in elections and influence the allocation of ministerial posts based on their collective power.

But that’s just part of it. To win elections, Japanese MPs need to get the support of local assembly members of the same party in their constituency, as well as influential people in their region. This means having ready funds to pay for food, drink, and gifts for these people, as well as hiring secretaries who will take care of them.

Local politicians follow the same playbook. For instance, up until three years ago in Kagawa Prefecture in western Japan, many prefectural assembly members each year handed out money to small local groups, like festival organizing committees and hobby clubs. The financial handouts were called “opinion exchange meeting fees.”

Reportedly, the money came from political activity fees provided by taxpayers. But as the funds were meant for policy-making, the practice was discontinued after a local TV station raised the issue.

Political parties allocate funds to support their members’ political activities. These funds are partially sourced from taxpayers’ money, referred to as Political Party Grants. Many politicians – particularly those from LDP – have argued, though, that these are insufficient, which is probably why the slush funds came about.

Factions hold their fundraising parties once a year. They sell tickets for these parties to individuals and corporations who may or may not show up at the event. In the case of the ongoing LDP scandal, factions did not declare portions of their ticket sales in their political-funds report. The undeclared amounts meanwhile went to favored members for them to do as they pleased.

So far, there have been no signs that the squirreled funds benefitted the LDP politicians personally. But there have been a number of cases in the past where the use of political funds has been questioned, such as for drinking with friends, traveling with family, and buying artwork and manga.

Yaichi Tanigawa, a former member of the House of Representatives from Nagasaki who resigned recently after being fined for failing to report kickbacks from the Abe faction, explained where he spent the money at a press conference: “I went out drinking, I went out to eat, I used it to build relationships.”

As for why he enthusiastically sold party tickets for his faction, he said: “I wanted to raise money and build up my power like a minister to deal with the issues in Nagasaki. I mistakenly thought that the ability to raise money was essential for a politician to become great.”

Yet Tanigawa was not entirely wrong to have seen things that way. The large sums of money politicians use to organize their supporters have helped secure their votes. Despite there being physical limits to getting more votes through personal connections, it remains a powerful means of winning elections, partly due to low voter turnout.

In Japan’s last three general elections, voter turnouts were ranging from 52 percent to 55 percent. When it comes to prefectural assembly elections, the figures have been at 44 to 48 percent. In other words, between half and nearly 60 percent of voters have been giving up their right to vote.

Even an increase of a few percentage points in voter turnout would significantly reduce the effectiveness of the organized vote. In the 2009 general election, when the LDP fell from being the number one party for the first time and a change of government took place, the voter turnout was 69 percent.

The danger now is that the LDP’s slush-fund scandal could lead to even greater cynicism among the public toward politics. Should that result in a further decline in turnout, politicians will fall into a vicious cycle of relying more and more on organized votes.

Prime Minister Kishida has been criticized by opposition parties for, among other things, his lax measures for improving transparency of political funds. But the real political game changer is no other than the Japanese electorate. ◉