|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

About twice a year, 23-year-old Hải journeys from his hometown in Vũng Tàu to Hanoi. There he immerses himself in the Four Palace ceremonies, a UNESCO-recognized ritual of the Vietnamese Buddhist “Mother Goddess” faith (Đạo Mẫu). This spiritual practice adds another layer to Hải’s religious life, beyond his regular Buddhist activities in Vũng Tàu.

As a member of the LGBTQI+ community, Hải – who requested a pseudonym for this story – said he experiences constant discrimination, which has led him to seek solace and strength in his spiritual beliefs. “I am a Buddhist at heart,” he told ADC.

But in official documents like his national ID card (both the old chứngminhnhândân and the new căncướccôngdân versions), Hai declares himself as non-religious (khôngtôngiáo) His entire family – also devout Buddhists – also do not disclose their faith in official paperwork.

“We do not want to mess with the government,” Hải explained. “Religion is a sensitive issue in Vietnam.”

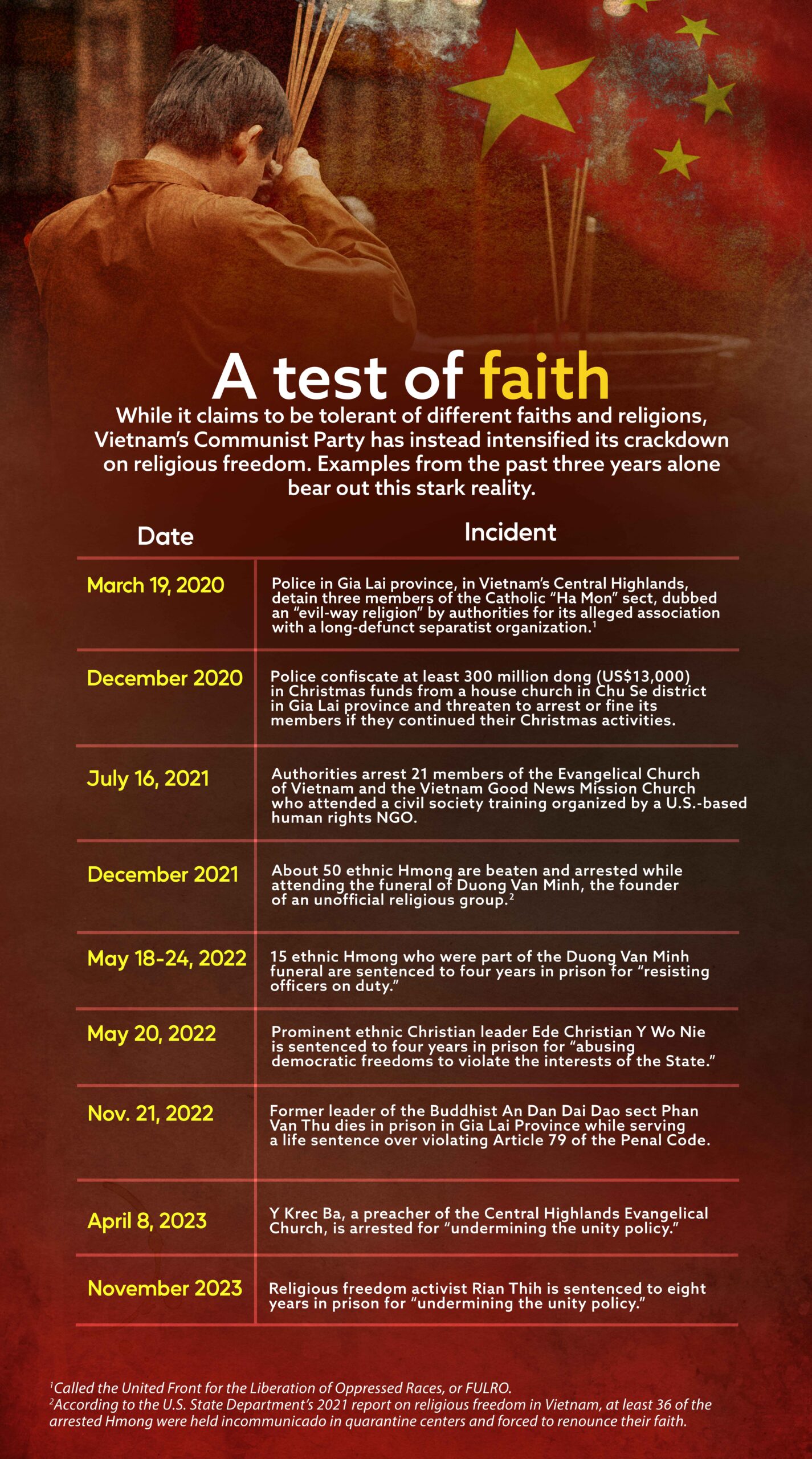

In its 2023 Annual Report, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIF) had recommended that Vietnam be designated as a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) for “engaging in systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations of religious freedom.”

Ahead of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Vietnam this April to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership, the faith-based legal advocacy organization ADF International and 70 international experts and groups, including the Asia Democracy Network (ADN), have also sent a letter to Biden administration officials, requesting them to raise concerns directly with Vietnamese leaders regarding Hanoi’s hostile stance toward religions that have been resisting government control.

This is even as Vietnam’s Constitution states that citizens “can follow any religion or follow none” and “all religions are equal before the law.” The constitution also mandates respect and protection for freedom of belief and religion.

Then again, the same charter allows the Communist Party-state to restrict human rights, including religious freedom, for reasons of “national defense, national security, social order and security, social morality, and community wellbeing.” Vietnam’s 2018 Law on Belief and Religion also contains similar provisions permitting restrictions on the right to religious freedom.

The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) tightly controls religious practices and beliefs, particularly among ethnic minorities. This discourages many Vietnamese from publicly declaring their faith, leading them to either discreetly practice their religion or even abandon some rituals altogether.

A small percentage of faithful

According to the white book on religions and religion policies in Vietnam that was released in March 2023, only 27 percent of the country’s 99.2 million people are “religious followers.”

However, this figure indicates the number of people who actually listed their religion on national ID cards or other major administrative documents, and not all of those who practice their faith openly or otherwise.

It’s not hard to see why many choose to keep their faith to themselves. A pastor who has been living in Hanoi for more than a decade, for instance, told ADC that the Vietnamese state surveillance is secret yet substantial at his church’s various activities that involve both Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese Protestants.

“Security forces often attend their sessions in plain clothes,” said the pastor.

Civil society organizations have also reported crackdowns on members of unregistered religious groups, particularly in the Central Highlands, Northwest Highlands, Southwest, and Central regions.

In May 2022, Vietnamese authorities held two closed-door trials for 15 members of the Duong Van Minh (DVM) religious community, an ethnic Hmong group. The individuals were sentenced to up to four years in prison on charges of “resisting officers on duty” (Article 330 of the Penal Code) and “violating safety regulations in crowded areas” (Article 295).

These stemmed from a December 2021 incident in Tuyen Quang province, during which police detained nearly 50 people who attended the funeral of Duong Van Minh, the ethnic Hmong founder of a religious community not officially recognized by the government.

Last November, Vietnamese officials violently attacked Buddhist monks and followers of the Khmer-Krom community at a temple situated in Đài Thọ Hamlet, in Vĩnh Long province. Weeks later, Thạch Chanh Đa Ra, the pagoda’s abbot, was expelled by the government-approved Vietnam Buddhist Sangha for being “uncooperative.”

Ethnic minorities in remote areas face particular challenges in trying to practice their faith, such as Hmong Christians and Montagnard Protestants. Anthropologist Dr. Paul Sorrentino has observed that the Vietnamese state has used the term “tàđạo,” often translated as “false religion,” in referring to the faiths observed by ethnic minorities, especially those who converted to Protestantism.

The term was first used by Emperor Minh Mạngin 1833 to describe the “evil way” of Catholicism. Interestingly, Protestantism is among the religious traditions that have a notable presence and state recognition in Vietnam, along with Buddhism, Hoà Hảo Buddhism, Cao Đài, and Catholicism.

‘Illegal’ worship

Vietnam’s religious landscape navigates a complex system of registration and oversight. To operate legally, religious organizations must register with the state-funded National Front of Fatherland. As of 2020, this system has recognized 16 religious and 43 organizations, while unregistered groups are automatically deemed illegal.

These groups are then usually charged with “abusing democratic freedoms” because, said one activist, they “refuse to be registered under a state agency.” But many of these groups reject registration for fear of persecution and losing their autonomy. In reality, the degree of religious freedom enjoyed by groups often hinges on their leaders’ relationships with local authorities, predominantly Community Party members.

Even exiled religious activists are not guaranteed safety, as illustrated by the case of Lù A Da. A former missionary, preacher at the Northern Evangelical Church of Vietnam and leader of the banned Hmong Human Rights Coalition, he and his family crossed the border into Thailand in 2020 to seek refugee status to evade persecution for his ethnicity and faith.

However, in late 2023, he was detained by Thai authorities for illegal entry. While in detention, he accused an official of the Vietnamese Embassy in Thailand, who had gone to the facility, of threatening him.

In the chapter he contributed to the book Histoire du Vietnam de la colonisation à nos jours (History of Vietnam, from colonisation to today), Dr. Sorrentino also noted that only members of organized religions are considered followers of a faith; those practising folk religions are not. At the same time, however, he said that someone known to have a religion was prone to discrimination and scrutiny, particularly those seeking to advance their careers within the Party.

Vietnam used to have a CPC designation in 2004 for its systematic and egregious abuse of religious freedom under the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act. But the United States removed Vietnam from its CPC list in 2006, paving the way for the country to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007 and embark on deeper and wider integration with the rest of the world.

On Nov. 30, 2022 – a few months after Vietnam became a Human Rights Council member – the U. S. Secretary of State in accordance with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 placed Vietnam on the Special Watch List for having engaged in or tolerated severe violations of religious freedom, along with Algeria, the Central African Republic, and Comoros.

Deputy spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Phạm Thu Hằng was quoted as saying in response: “The putting of Vietnam on the U.S. Special Watch List regarding religious freedom was based on evaluations that were not objective, as well as inaccurate information on the freedom of religion and belief in Vietnam.”

A threat to state authority

For sure, the ability of religions to gather, inspire, and lead large numbers of people could be seen as a threat by the state to its authority. But the apparent wariness – if not distrust – of the government toward religions and practices connected to faith seems to be based as well on its persistent association of such with foreign influences.

For example, Roman Catholicism was introduced to Vietnam through the efforts of French missionaries and was part and parcel of the country’s colonial era. In the context of the Indochina war, numerous Hmong Catholics aligned themselves with the French in their struggle against the Communist regime.

Prominent Catholic leaders have also voiced their opposition to the expulsion of impoverished individuals, outshining the government’s efforts in serving the underprivileged. Likewise, Buddhist activists have struggled to reclaim their right to freedom of expression, which has been limited within the country.

In the 1990s, a significant number of Hmong communities embraced Protestantism due to their exposure to a U.S. radio station broadcasting from the Philippines. Hmong who had migrated to the United States were also instrumental in exerting pressure on Washington to denounce religious oppression in Vietnam.

The government’s treatment of religions, regardless of their registration status, has led even those who claim no political opposition to feel apprehensive about practicing their faith.

A young professional in Ho Chi Minh who wants to be referred only as Vũ said that his family members, having no problems with the government, have no qualms writing down their religion (Roman Catholic) even on official papers. But they do not go to church, opting just to read the Bible on their own.

During the 1950s, the Communist government had aimed to infiltrate villages and replace traditional elites with Party members purportedly to revolutionize rural life. But Catholic communities opposed the replacement of their parish priests with Party cadres. The tension between Catholics and communists resulted in a significant exodus of an estimated 700,000 northern Catholics to South Vietnam after the Geneva Agreement of 1954.

Vũ’s family was among the dânbắcnămtư, or the northerners who chose to migrate south in 1954. This made his family have a rather “ugly background,” and so they have tried to ensure that they remain under the radar. Said Vũ: “It is better not to be paid attention to by the government.” ◉