|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Farmers of Kashmir’s famed saffron had a bumper harvest last year, just like the year before, but Aqib Bashir Ganie didn’t seem too happy last November as he delicately plucked the season’s last saffron flowers and placed them in a wicker basket.

Ganie’s family once had almost three hectares of land under saffron cultivation. Today they have just one hectare of saffron land; the rest has been converted for alternative crop production.

“Due to the gradual decrease in the production of saffron in the past three decades, our saffron land has been shrunken to a husk of what it once was,” the 28-year-old told ADC.

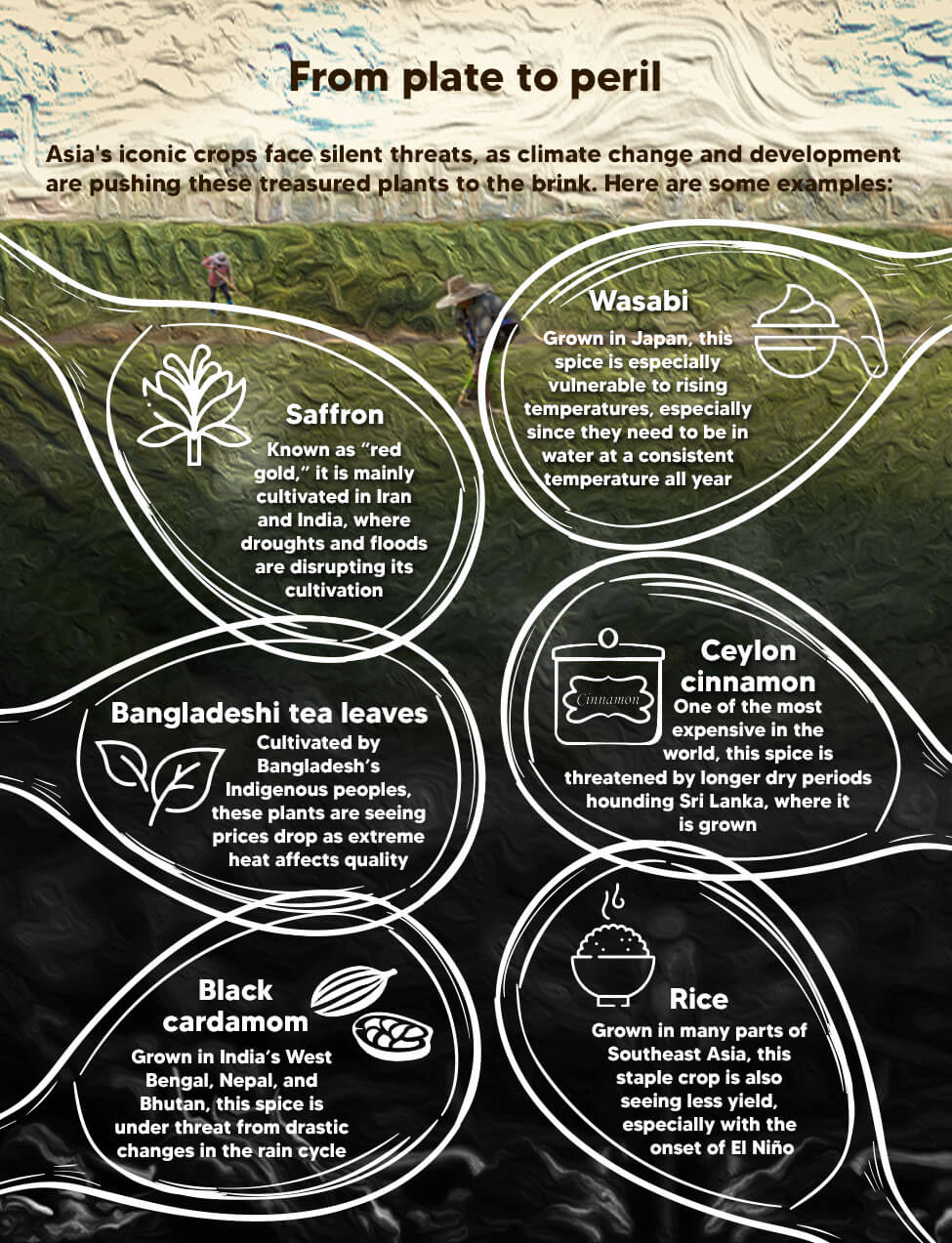

Kashmir is the second largest saffron-producing region in the world after Iran and is the only place in India so far where saffron is produced. Iran accounts for 88 percent of the world’s saffron production, while India is a very distant second with 7 percent. The rest comes from Spain, Greece, Italy, and other countries.

Kashmiri saffron, however, is considered special and of high quality, with research revealing a higher level of crocin content in the spice coming from the valley. A carotenoid chemical compound found in the flowers of crocus and gardenia, crocin is primarily responsible for the color of saffron.

Higher crocin content gives Kashmir saffron its distinct darker color and stronger aroma, as well as increased medicinal value – thereby helping it command a higher price than saffron from other places.

Saffron cultivation in Pampore, where 90 percent of the spice in Kashmir comes from, has also been recognized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. The spice is part and parcel of the region’s cuisine and culture, with many believing that Sufi saints Khwaja Masood Wali and Hazrat Sheikh Sharif-ud-Din blessed Kashmir with saffron crops in the 12th century.

Despite all these, every saffron farmer in Kashmir interviewed for this report echoed Ganie. They said that due to less production of saffron for many years, they have switched some of their saffron land to alternative crop production or left their land uncultivated. And while they concede that climate change has been having a significant impact on saffron farming, they lay the bigger blame on the central government for Kashmir’s dwindling saffron crop.

This is despite the constant promotion of Kashmiri saffron by central and local officials and the National Saffron Mission (NSM) that the central government launched in 2010 to revive and revitalize saffron production in the region.

Nature’s wrath and government’s ineptitude

Besides providing irrigation through sprinklers and taps and increasing the quality of the seed sown for crops, the mission also had plans to tackle climate-change woes.

Yet Ganie said, “We have been battling climate change amidst government inaction for many years. If the present situation persists, in the future we may have to completely wind up saffron production.”

“The change in climate like rising temperature and erratic rainfall have taken a toll on saffron production in Kashmir,” said Abdul Aziz Sofi, a 65-year-old saffron farmer in Pampore. “However, our struggle is compounded by the apparent lethargy of the government in addressing the challenges posed by shifting weather patterns and environmental degradation.”

Nadeem Qadri, an environmental lawyer who also has saffron land, said, “Climate change is indeed decreasing the production of saffron, but authorities should be ready to tackle these difficult situations.”

Yet according to him and other farmers, the government had even failed to meet the irrigation requirements of saffron farming.

A 2010 study by the Sher-E-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology had found that 128 bore wells were needed to cultivate saffron. Since then, however, the Public Health Engineering and the Irrigation and Flood Control Departments have constructed only three bore wells that Qadri said do not even work.

“If you visit saffron fields, you will not find any functional bore well,” said Qadri.

“Allah blessed farmers with timely rainfall in 2022 and 2023 and we witnessed good results in saffron production,” he said. “It also indicates how much irrigation is essential for the crop that the administration failed to provide farmers.”

According to the Jammu and Kashmir agriculture department, the area under saffron cultivation in the valley decreased from 5,707 hectares in 1997 to 3,500 hectares in 2017. Saffron production decreased from 15.85 million tons in 1997 to 9.6 million tons in 2017.

In a report on last November’s bumper crop, Indian media outlet News18 said that the region is currently producing an average of 2.34 tons of saffron annually, or less than a fourth of its output just six years prior. This February, no less than Agriculture and Farmers Welfare Minister Arjun Munda was quoted in media as saying that Kashmir’s saffron production had declined by 67.5 percent between 2010 and 2023. But he also said that “during the last one year from 2022-23 to 2023-24, the saffron production has marginally increased by 4 percent.”

According to the online publication Kashmiriyat, Munda said that 123 bore wells had been built and that 73 of these had been “successfully connected…with the Sprinkler Irrigation Systems having a command of 2,187.08 hectares.”

“However,” Kashmiriyat quoted Munda as saying, “the irrigation facilities are not being utilized fully as the User Groups for management and upkeep of these bore wells have not been created as per the Mission Guidelines and have not been handed over to the farmer user groups.”

Mission of misses?

Data from the Department of Agriculture say that around 30,000 families in Kashmir are dependent on saffron cultivation; the sector is employing about 5 percent of the rural workforce in the valley. Besides Pampore, other areas that grow saffron in Kashmir are Kishtwar, Srinagar, and Budgam.

Kashmiri saffron comes in several varieties, among them mongra, which is the darkest in color, and lacha, which comes with both red and yellow parts. Zarda, yet another saffron variety, is used in face packs, beauty creams, and moisturizers.

Saffron harvesting season in Kashmir runs from mid-October to mid-November. In the autumn, it is common to see entire families out in the saffron fields, picking the light purple flowers and piling them in wicker baskets. The spice is actually the flower’s dried red-orange stigma. After spreading the harvested flowers on a clean sheet laid on the ground, family members take off the stigmas by hand, flower by flower.

Kashmir agriculture director Choudhary Mohammad Iqbal told ADC that the government has been fulfilling its mission to revive and develop saffron production in the region. “We have already rejuvenated almost 70 percent of proposed saffron land under the National Saffron Mission,” he said. “We have also increased the production of saffron from 1.8 kg per hectare to five kg per hectare.”

In addition, an official NSM document said that 2,578.75 hectares of saffron land has been rejuvenated out of the 3,715 hectares proposed for such under the mission.

Moreover, Iqbal said that the Geographical Indication (GI) tagging of saffron has increased its value and price. In May 2020, Kashmiri saffron was given a GI tag by the Geographical Indications Registry, making it illegal for anyone outside the valley to make and sell a product as ‘Kashmiri saffron.’ Said Iqbal: “Earlier, saffron was sold at INR 70,000 (US$844) per kg, and now its price is INR 200,000 (US$2,410) per kg.”

Under NSM, authorities also established India International Kashmir Saffron Trading Centre (IIKSTC) in 2020 in Pampore.

“It acts as a bridge between saffron growers and the market,” said Tariq Ahmad Parray, who is in charge of collection at the center. “Our job starts after farmers harvest saffron crops every year. We provide space to farmers for separating stigma from flowers, dry it with the help of vacuums, and store their crop in our cold store.”

The IIKSTC has a 450-seating capacity, while farmers who sign up at the center can keep their saffron at the cold store for two years. It also provides quality tests done by machines and guarantees of originality. “The main thing that this center does is that it maintains the originality of the crop,” Parray said. “We have around 600 farmers connected to our center.”

He said that the center does an international e-auction of saffron. “In 2021 we sold 50 kg of saffron, (in) 2022 we sold 87 kg.” As of last November, he said, they had sold “around 150 kg of saffron” for 2023.

But most of Kashmir’s farmers prefer to sell their saffron on their own, and either export it or sell to domestic saffron stores. According to the farmers, they have to wait until they get their turn if they sell their crops through IIKSTC. They also said that the center takes too long to sell their crops.

“This scheme would have been helpful only if officials of the IIKSTC would provide us money in hand once we give them our crop,” said Tanveer Ahmad Rather, a young saffron farmer. “You can find last year’s crop still stored in the cold store.”

To most Kashmir saffron farmers, NSM has simply failed them. Meanwhile, the government has extended NSM to India’s northeast, where it apparently believes climate-change challenges would be easier to address.

“There should be an enquiry into the NSM,” said Qadri. “If authorities are claiming they have spent 400 crore rupees (US$48.2 million) to uplift saffron farmers, then why haven’t they gotten results yet?”

“We had always been vocal in demanding government intervention,” veteran saffron farmer Sofi said. “We seek sustainable solutions, including the implementation of climate-resilient farming practices and improved irrigation infrastructure.”

“The significant income from this crop has helped our elders in building houses and marrying off their children,” said young farmer Rather. “But, it seems, the day isn’t far when we will see saffron fields left barren, without any crop production.” ◉