|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

F

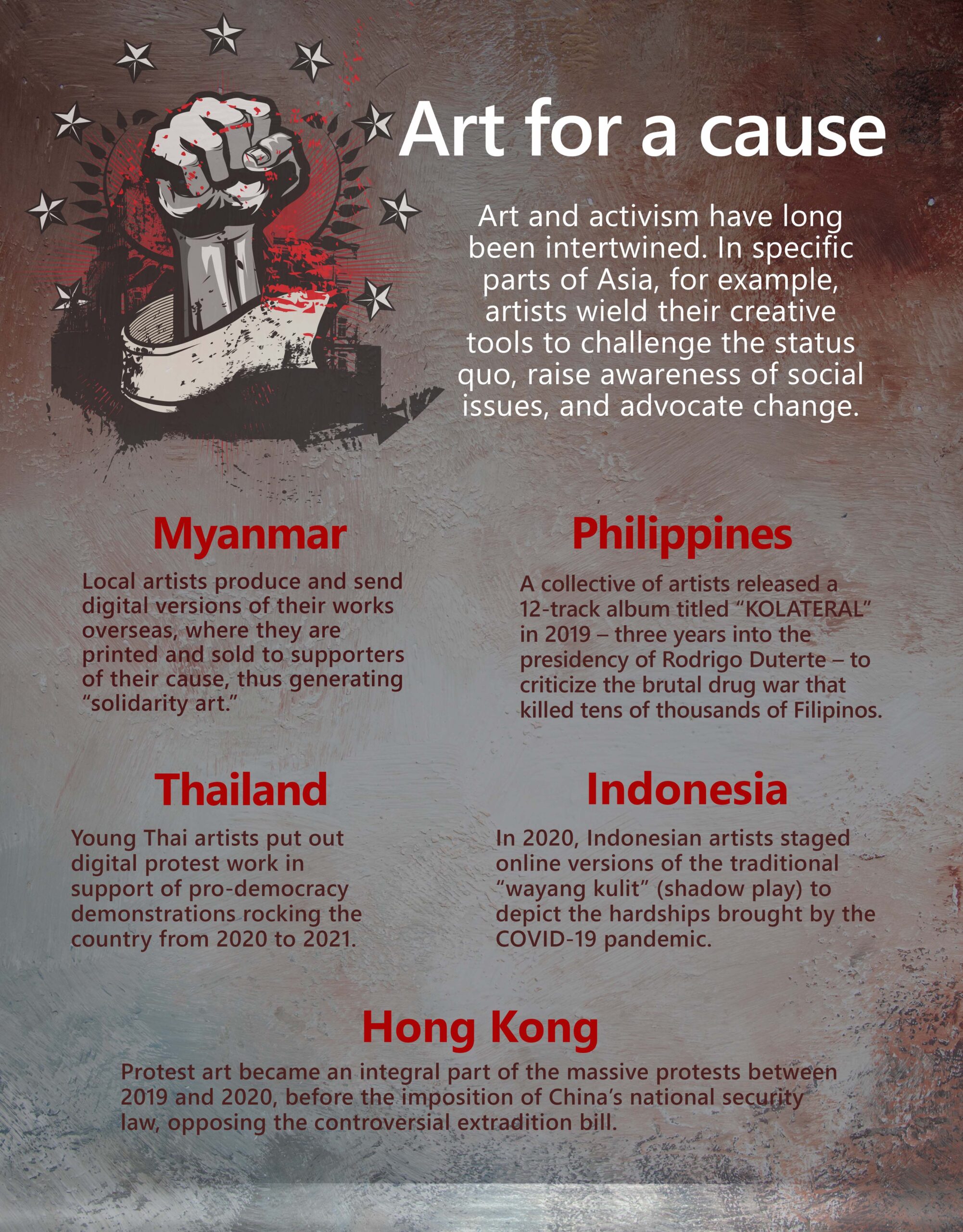

rom silent strikes to the banging of pots and pans, to self-immolation and the taking up of arms – for the last three years, the people of Myanmar have been making clear just how much they unequivocally reject the return of their country’s military to power.

Outside of Myanmar, their compatriots are also making themselves heard. Just last Feb. 1 – the third anniversary of the latest power grab by the Tatmadaw (as the Myanmar military is called) – Myanmar artists were joined by their Thai colleagues in a two-hour protest in the guise of a performance-art festival.

Organized by the Thai-Myanmar Activists Network, the event was held at the popular tourist destination Tha Pae Gate, in the Thai northern city of Chiang Mai, nearly 700 kilometers from Bangkok and 365 kms from Yangon, Myanmar’s financial capital. Beyond entertainment, the songs, spoken-word, and performances delivered potent messages that left hundreds of spectators deeply moved, some even to tears.

“Art is a visible expression of what you feel and how you feel,” said Yadanar Win, a prominent Myanmar performance artist. “At the same time, it also has the power to convey and trigger the emotions of the audience, serving as an awakening strategy to garner special attention.”

AKT, a Chiang Mai-based Myanmar activist, also said, “We refer to ourselves as ‘artivists,’ a combination of artist and activists, who use our art forms of activism in the anti-coup resistance and the Myanmar democracy movement.”

Indeed, “artivists” from Myanmar have been using performance art in the last few years not only to convey their resistance to military rule, but also to remind the international community of the continuing plight of the people of the conflict-torn Southeast Asian country. With global attention diverted by other conflicts, Myanmar activists feel a heightened urgency to bridge the information gap and amplify the voices of those suffering inside the country.

One artist based in Chiang Mai said that they deliberately choose tourist sites for their performances to raise the chances of their message reaching not only the locals, but also overseas visitors.

Performer AKT said that, as a result, their events typically receive coverage from both local and international media. For instance, dozens of media outlets attended the recent Chiang Mai event, which was called “Up Against Dictator-Shit,” and reported on it in English, Thai, and Burmese.

“Performance art always sends a strong and clear message to the spectators,” said Thai activist P Por. “Every voice and action from performers strike through spectators’ senses and emotion. The motion and acting immerse us in the experience, pain, and emotion of performers as if we are experiencing these ourselves.” He added that performance art is “really impactful as an advocacy tool and awareness raising.”

But art is also a means of expressing what one feels or thinks of a situation or issue while also being a means to heal. In a March 2023 article on solidarity art from Myanmar, Susan Banki, sociology and criminology chair at the University of Sydney, noted that while art “can be a form of resistance … its power is both healing and demanding attention – allowing survivors of trauma to resist against the feeling of disempowerment to demand alternatives to abuse witnessed and suffered.”

Art from the heart

Freedom of expression has been absent in Myanmar since the 2021 military takeover. Yadanar, though, managed to put up a performance that she called “Bloody Coup” before the Tatmadaw tightened the screws on the people’s freedom to a choking point. During that performance in downtown Yangon just 18 days after the coup, Yadanar and another artist sat facing each other while holding protest signs; nearby, blood dripped from a bag.

“I demonstrated how the people had been killed during the protest,” Yadanar explained. The main message, she said, was that ‘democracy has been full of blood and people have been dying.’”

But the Tatmadaw became even more vicious and artists – and most of Myanmar’s people – were no longer able to express themselves as freely as before. This fired up the Myanmar artists who were based outside of the country to become the voice of their compatriots.

In March 2021, at an international academic conference on Myanmar in Chiang Mai, AKT and other Myanmar and Thai artivists had a surprise performance that depicted the violent crackdown of the Tatmadaw on protesters. That, many say, was probably the first anti-Myanmar coup performance art in Chiang Mai.

It has hardly been the last, however. In fact, performance art has become part of rallies organized by the artivists in Chiang Mai, highlighting issues like the hanging of civilians in Myanmar (via “The Stars Are Falling,” performed on July 26, 2022) and the handing down of death sentences to seven university students in December 2022. Marking the 8888 Uprising – a student-led revolt in August 1988 in Myanmar that saw yet another brutal response from the military – included performance art as well in 2022 and 2023.

And when a government airstrike targeted a civilian refugee camp in Kachin state in October 2023 that resulted in the death of 29 civilians, among them 13 children, artivists channeled their grief into a sorrowful performance art piece at Tha Pae Gate. Recalling the reactions from the spectators to these performances, one artivist said, “I could see people crying and becoming emotional.”

“When people can feel the experience of others is when the people can empathize more,” said one Thai artivist. “Then when people have empathy toward the issues, they will support the cause.”

The performers themselves concede that what they have been doing is unlikely to result directly in overthrowing the junta in Myanmar. Yet they argue that the media coverage and public attention garnered by their performance pieces can play a role in influencing change. They believe sustained public attention could help pressure the junta to tone down its brutality.

Heightened and widespread public awareness may also prompt relevant international actors to take more decisive actions on what is happening in Myanmar. Performer AKT, for one, believes that if an art piece on the death penalty gains enough public attention, it could at least open a discussion on the issue, and eventually contribute to the lessening of severe sentences.

More than a helping hand

The Myanmar artivists, though, are sure that they would be unable to successfully mount such performances in Chiang Mai were it not for the steady help and support from their Thai colleagues. One artivist says that the “frontline team” for performances always include “Thai activists and lawyers to deal with the police or any potential threat during the event.”

But support from the Thais go beyond legal and logistical concerns. During a performance art protest addressing the military’s airstrikes, for example, Thai artivists joined hands with their Myanmar colleagues, showcasing a unified front in calling for change.

AKT also said that networking with Thai performance artists has facilitated and increased the advocacy activities of Myanmar artivists in Chiang Mai. He emphasized their regular collaboration with the Thais, envisioning other potential joint efforts for collective advocacies. He cited the collaboration they had on the issue of the death penalty in Myanmar that enabled them to come up with impactful performance-art activities.

Just like the Myanmar artivists, AKT added, the Thais are also committed to keeping the public informed about what is going on in the country next door, as well as to sustaining attention on Myanmar affairs through their artistic works. Other Myanmar artivists underscored the enabling role played by the Thais, pointing out that the support and solidarity of Thai performance artists and advocates have empowered them to engage in more extensive performances.

Thai activist P Por, for his part, explained why he and other Thais have been keen to help the Myanmar artivists: “Thai and Myanmar people shared the same struggle from the military since the end of World War II. For me, Myanmar people are our friends and we need to support each other.”

“I have seen performance art quite often since I moved to Chiang Mai from both Thai and Myanmar activists,” he also said. “I’m always touched by these performances, especially the performance after the airstrike in Kachin state. I can feel pain, fear, and trauma in the performance. This makes me empathize more with our Myanmar friends.

“I wish our friends victory and a good transition. I hope one day we can meet each other in your home, when it is safe and free,” he added. ◉