|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In a small, sunlit room, surrounded by her bandmates, Tao Aves closes her eyes and sings: A long time ago, bullet storms blotting out the sun / Were not a threat to schools.

It’s imagery that, elsewhere in the world, would probably not make sense. But in the Philippines, where extrajudicial killings have become a norm, “bullet storms” — shootings — have come to characterize how activists, dissidents, journalists, and even teachers and healthcare workers, are being gunned down in the guise of suppressing the communist insurgency.

This was the case for Chad Booc, a 28-year-old activist and volunteer teacher for the lumad (Indigenous peoples) in the Philippines’ southernmost region Mindanao, and for whom Aves had written her song. On Feb. 24, 2022, he and his fellow teacher Gelejurain Ngujo II, health worker Elgyn Balonga, and their drivers Roberto Aragon and Tirso Añar were killed in what the military called an encounter between soldiers and Booc’s group of “communist rebels” in the village of Andap in Davao de Oro province.

But even in death, Booc resisted the military’s claims of an encounter. An autopsy of his body showed that the former math and science teacher died instantly in a “hail of bullets fired with an intent to kill.” This image fuels Aves’s sorrowful elegy to Booc, in which she growls: The military in the countryside must leave, must pay.

The song, simply titled “Chad,” is one of three portrait songs written in Filipino by Aves’s band Oriang to commemorate three Filipino activists: Booc, poet-guerilla Kerima Tariman, and women’s rights activist Amanda Echanis. The goal isn’t just to memorialize them in art, but to pass on their stories of heroism through music and song in hopes that these could touch young people.

Educator for Indigenous peoples

“We are under no illusion that songwriting (alone) will free the masses,” Aves tells Asia Democracy Chronicles (ADC). “What we do acknowledge is that [revolutions] are the territory of hearts, minds, and bodies, and that the actions of these bodies do draw influence from text and storytelling. And text and storytelling, they are long-standing tenants of music.”

This belief propelled Oriang — a band of mostly female and queer artist-activists named after Gregoria de Jesus, one of the founders of the Spanish colonial-era revolutionary group Katipunan and wife to Philippine hero Andres Bonifacio — to submit their songs to be part of the Libraries of Resistance project by Innovation for Change — East Asia (I4C-EA), a regional network seeking to build a stronger East Asian civil society

Believing in the power of storytelling as a catalyst for change, the project hopes to be a “repository of lessons and visions of resistance, solidarity, and inclusivity” across East Asia and Southeast Asia.

Revolutionary poet

Resistance fighter and poet Kerima Tariman, who was slain in an encounter with the military on Aug. 20, 2021 in Negros Occidental, is also a mother to Eman Acosta, one of the collaborators involved in the Oriang project. Lyrics in English and Filipino by Oriang.Pain put to music

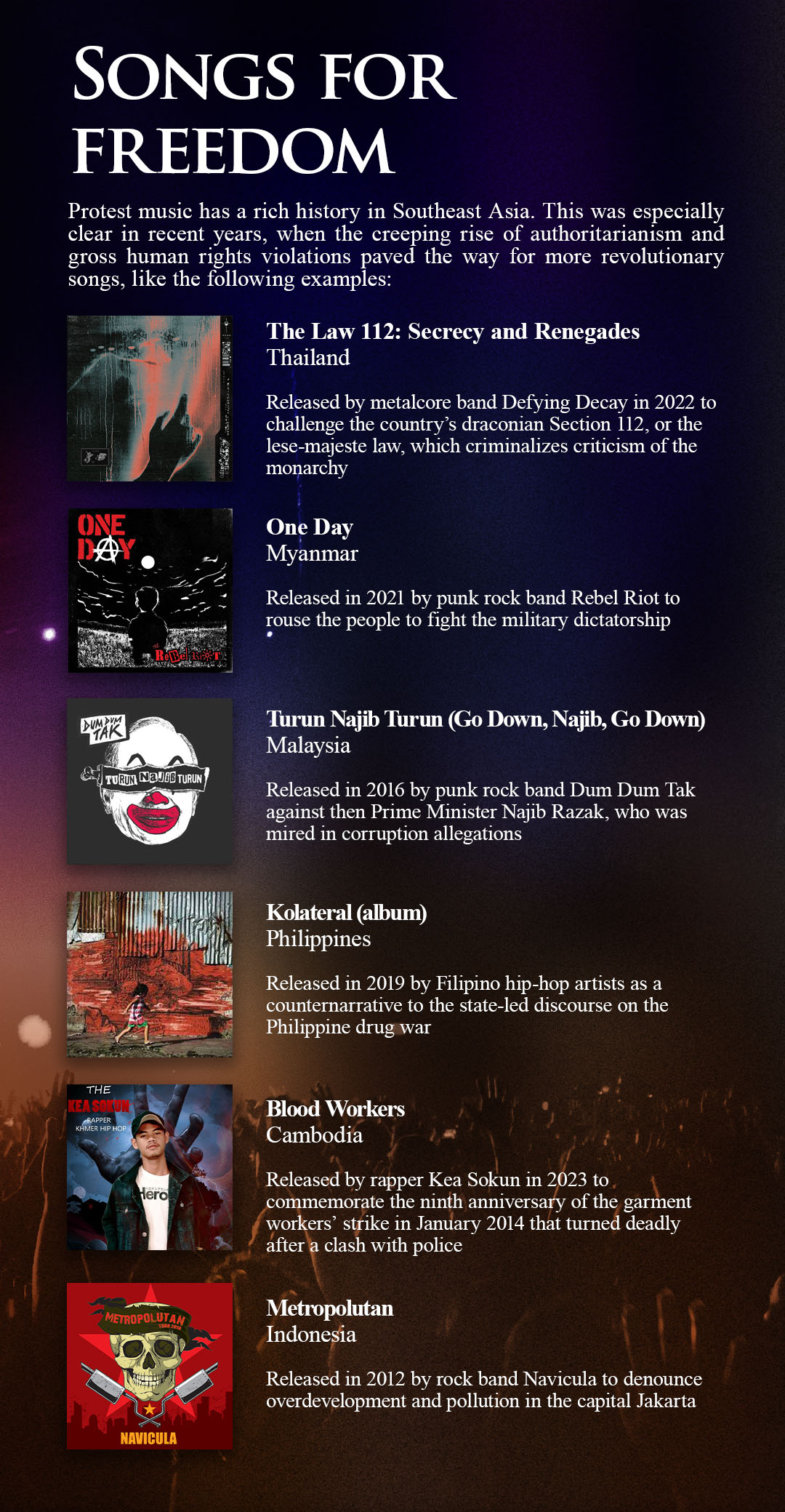

The Philippines has a long tradition of using protest music as a tool for resistance. From the rebellious anthems written during the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos Sr., to the hip-hop songs raging against former President Duterte’s war on drugs, to the modern protest songs railing against the controversial 2020 anti-terror law, Filipino artists have long used songs to express their dissatisfaction with the status quo and to rouse people into action. “Bayan Ko (My Country),” a protest anthem that gained popularity during the Marcos Sr. dictatorship, was written when the Philippines was still a U.S. colony.

Aves’s dreams, however, are much more modest. Now a mother to a 14-year-old who is growing up in a country “where good deeds often become misinterpreted and portrayed as an evil,” Aves says that she wants to show her child “a different portrait of what heroism can look like.”

A graduate of the state-run Philippine High School for the Arts, Aves says that her own idea of heroism has been shaped in large part by her fellow artists and activists who introduced her to rights defenders and community organizers doing the hard work on the ground. And so for her, heroism is “serving the people: tilling the land, calling to raise wages and lowering the cost of living, volunteering to teach lumad youth.”

Activist playwright

‘Amanda Echanis, daughter of slain peace consultant Randy Echanis, spent the first months of motherhood in jail after she was charged with illegal possession of firearms by police in Cagayan province, located in the northeastern region of Luzon. Lyrics in English and Filipino by Oriang.But this is also the kind of work seen as suspect by the Philippine government, which views activism as adjacent to rebellion. This was especially clear under the former Duterte administration, which saw at least 427 activists, rights defenders and grassroots organizers killed by December 2021; 23 journalists dead as of April 2022; and 195 environmental defenders killed by the time Rodrigo Duterte finished his term.

These numbers do not capture the scores of others — including doctors and the religious — who have been red-tagged (accused as communists), arrested and arbitrarily detained, tortured or even forcibly disappeared.

And yet, Aves notes, rights defenders and activists continue to put themselves at great risk to fight for marginalized communities and to speak out against injustice. It’s also why Oriang chose Tariman, Booc, and Echanis — all three of whom were had fallen victim to state oppression and injustice but soldiered on in their respective advocacies. Says Aves: “While the culprits of these injustices against these three are the same — the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Philippine National Police — the more prominent characteristic we know that they share is who they fought for: farmers, Indigenous peoples, women and children, and other oppressed communities.”

Aves and Calix, a hip-hop artist who produced the anti-drug war album Kolateral (released 2019), helm Oriang. Also among their collaborators are fellow musicians and songwriters Ymi Castel, Camoi Miraflor, Aki Merced, Bea Fabros, Geela Garcia, and Eman Acosta.

All of them share the same vision of lending a face to those whom the state has labeled “enemies,” Aves says. Beyond their activism, she asserts, Booc, Tariman, and Echanis were also artists and teachers, and the latter two mothers. That, says Aves, is what they hoped to highlight in their songs.

Tariman was 42 when she was killed by state forces in Silay City in Negros Occidental province on Aug. 20, 2021. She was part of the underground movement, but she was also a poet and a mother. She shared the same high school with Aves, who read her poems that inspired her as a musician: Mother to mother, I am guided by / The sharpness of your telling, Kerima. Tariman’s 20-year-old son, Eman, also grew up to be a songwriter – and he is working with Oriang on their songs.

Aves also knew Amanda Echanis, 35, playwright-activist and daughter of slain peace negotiator Randy Echanis, from childhood. Both had attended the same elementary and high schools, and they had worked together in two stagings of Echanis’s play “Nanay Mameng: Isang Dula,” which paid tribute to the late urban poor activist Carmen “Nanay Mameng” Deunida.

Echanis, who along with her infant child, was arrested in a police raid at her home in Baggao, Cagayan province, in the northeastern region of Luzon, on Dec. 2, 2020. She remains in detention along with her son, now three years old.

Police said that they found two hand grenades, an M-16 rifle, a loaded magazine and ammunition in her house – a claim that activists and rights groups found outrageous. It was raining when they insisted / That a mother had grenades in her home / That Amanda had too much power … While only placards and pencils were the contents / Of the home where she sang lullabies to her one-month-old baby.

A cum laude graduate from the University of the Philippines – Diliman who volunteered to be a mathematics teacher for a lumad alternative school in Surigao del Sur province, Booc was likewise remembered for carrying on his back the science of the land and the mathematics of taking a stand.

In all three songs, Aves addresses her own child, who enjoys comforts precisely because there have been people who chose to look beyond themselves and fight: As your agency takes shape / The challenge posed to us to ensure you are free.

In writing the songs, Aves says that she is aware her teenager will be listening to music that “directly or indirectly speaks to the conditions of the world the songwriter lives in, and will inevitably inform how they respond to the struggles they will inherit from us.

“I wouldn’t presume to prescribe how a fellow musician must conduct their artistic life,” says Aves, “but would pose the following challenge: what kind of generation are we raising with our work? Upon whose conscience have we directed our voices? If I leave my child with very little on this earth, it will be the signposts pointing in the direction of what a heroic life can look like.”

“I wouldn’t presume to prescribe how a fellow musician must conduct their artistic life,” says Aves, “but would pose the following challenge: what kind of generation are we raising with our work? Upon whose conscience have we directed our voices? If I leave my child with very little on this earth, it will be the signposts pointing in the direction of what a heroic life can look like.”

Her songs speak not only of the three activists’ lives, but also of what Aves wants to leave behind for her child: This is the time of questions / This is the time of a violent rush of rage / Our only nightmare is that you grow up in fear / Our only objective is to leave you with medicine.

For now, she says, Oriang plans on producing nine more tracks that explore other “heroes’” lives. These would make up a full album in collaboration with other artists working on similar themes. Aves says that they hope to write about, among others, the “Philippine peasantry and what the rich history of activism in art has been.

“I want to be very clear that I am a musician with a day job and am by no means an academic,” Aves says. “I do not have my pulse on larger discussions around what nation-building can and should look like, but I do believe [that] to persist in being alive under the thumb of incognito state fascism, of an imperialist enterprise, is maybe two percent of Step 1 toward that.

“Heroism is also the work of nurturing and not always the valor of running toward the battlefield,” Aves adds. “The model for heroism is the example being set by the masses who receive the brunt of state oppression.” ◉