|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

n the last two months, many eyes have been on Pakistan’s efforts to deport as many undocumented Afghans as possible in response to escalating attacks that it says are by groups backed by the Taliban in Afghanistan.

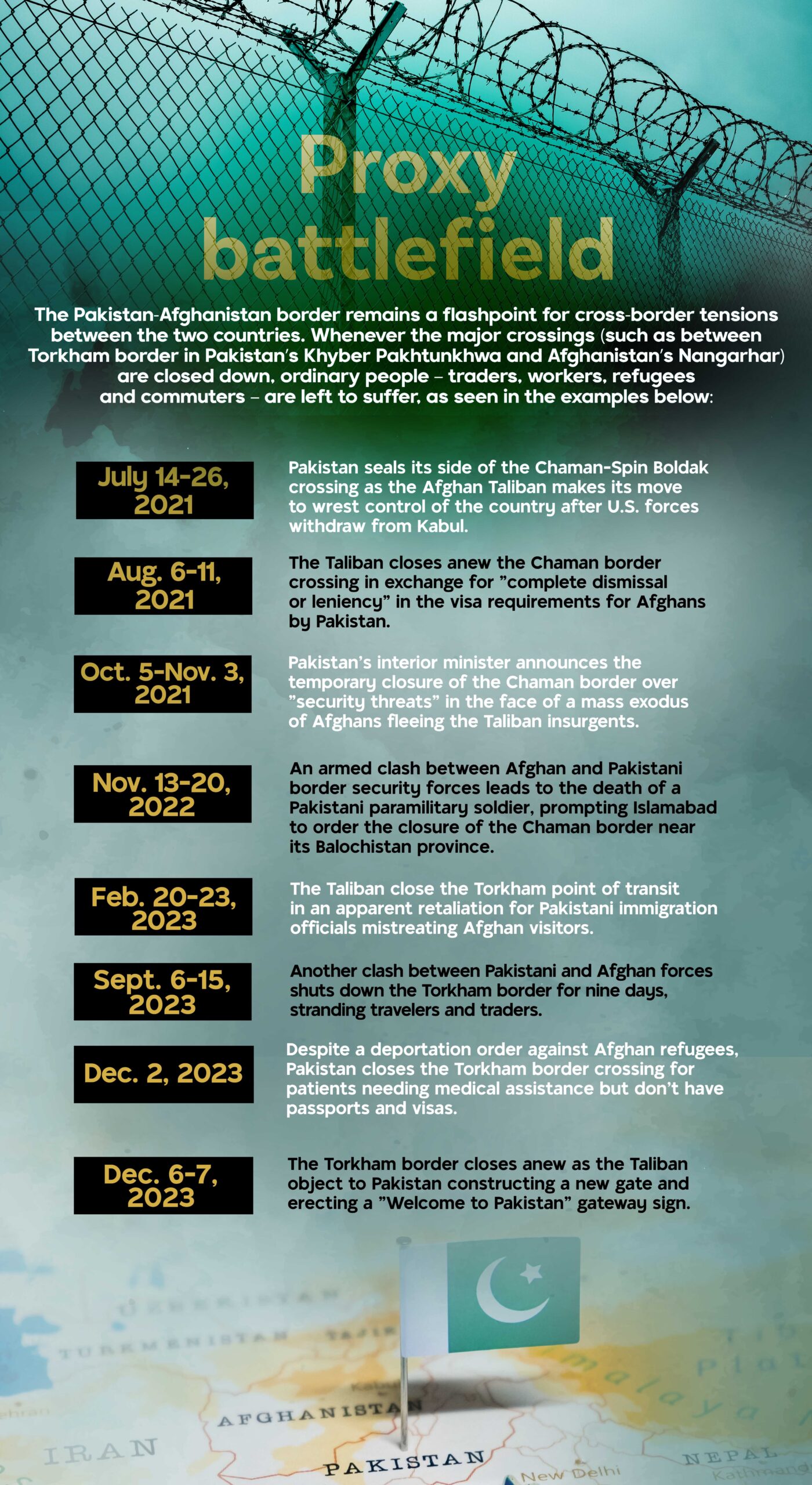

But the bickering between Pakistan and the Taliban has already been causing chaos at the borders for months on end, with authorities from one side suddenly shutting down gates because of a particular act by the other, and then opening these up again after some hurried diplomatic exchanges.

In one of the more recent border tiffs, Pakistan started demanding crews of commercial vehicles from Afghanistan to have passports and visas, prompting Afghan authorities to deny entry to Pakistani vehicles trying to cross into Afghanistan. The next day, however, trade resumed after Pakistan agreed to suspend the rules.

Just last September, Pakistan closed its gates at Torkham, between Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province and Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, following an exchange of gunfire between the security forces of the two countries. The border reopened after 10 days.

Observers, however, say the sudden shutting of borders between Pakistan and Afghanistan is likely to keep on happening. That is certainly not good news to small-time traders who cross from one country to the other regularly to make a living, but are now losing money as the borders keep on closing with little warning. According to one media report, the September shutdown alone translated to a total trade loss of about US$1 million.

There are other losses to consider, though. Afghan trader Fazal Muhammad, for instance, had to wait at the border for six days recently and was forced to spend over PKR 10,000 (US$35) on food and shelter — money that he said he could have used for his family. According to Muhammad, the amount was twice what he usually spent for his business trips.

“The border closed just as I entered Pakistan for my deliveries,” the 35-year-old told ADC. As he and his fellow traders waited for the border to reopen, he said that “there was a shortage of food and water, and the risk of theft.”

“When the border is closed, we have to wait for days,” confirmed 34-year-old Hayat Hussain from Pakistan’s Khyber district. “Our families worry about us, and we end up spending more money on food, places to stay, and fixing our trucks because they get damaged from carrying heavy loads for so long.”

Tussling over the TTP

Despite a seemingly pro-Islamabad government in Kabul led by the Afghan Taliban, the tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan have escalated over the years. One major point of contention is Kabul’s consistent rejection of the Durand Line as the official border between the two neighboring states. Running some 2,600 kms, the border has 18 crossing points between the two countries, of which Torkham is the busiest, along with Chaman.

But the big, sore point for Pakistan right now are the escalating attacks on its military installations by what it says are groups supported by Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers. Indeed, experts believe that the menace that is the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan or TTP is at the heart of the souring relations between the two countries, as their disagreement over the issue has recently resulted in clashes between their respective security forces, intensifying tensions and eroding trust.

Since the Taliban regained power in Afghanistan in August 2021, the TTP seems to have been emboldened and has scaled up its attacks on the Pakistan military. It also appears to be getting help from other groups.

On Dec. 12, at least 23 people were reported killed in an attack on a police station in a town in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The attack was later claimed by the Pakistani group Tehreek-e-Jihad Pakistan (TJP), which says it is affiliated with the TTP.

In a recent televised interview, Pakistani Caretaker Prime Minister Anwaar ul-Haq Kakar stated that more than 2,000 Pakistanis have been killed as Pakistan witnessed a “60-percent surge in terror incidents and a 500-percent increase in suicide bombings” since the Taliban took control of Kabul two years ago.

Kakar said that 15 Afghan nationals were revealed to have been among the suicide bombers, and that 64 Afghans died fighting Pakistani forces this year. He attributed the violence to the TTP “terrorists” based in Afghanistan and who are ideological allies of the Afghan Taliban.

Zabihullah Mujahid, Taliban’s deputy spokesperson, said in a statement posted on the group’s official account on X (formerly Twitter), “The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is not responsible for maintaining peace in Pakistan. They should solve their internal problems by themselves and not blame Afghanistan for their failures.”

Michael Kugelman, Asia Program deputy director and senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC, explained that one significant factor in the tiff is that the Taliban, which once relied on Pakistan for support during its war against Western forces, no longer sees Pakistan as its patron. Consequently, the Taliban feels less inclined to address Pakistani concerns or fulfill their expectations.

“The Pakistanis have been very frustrated with the Taliban for not doing more to help them on the TTP issue,” Kugelman told ADC.

At the same time, however, Kugelman noted that the long-standing ties between the Taliban and the TTP have made it unrealistic for Pakistan to expect the Taliban to readily address its concerns. This unmet expectation has contributed to growing frustration and disappointment in Pakistan’s dealings with the Taliban, he said.

Forcing the Taliban’s hand

Islamabad, though, seems determined to force the Taliban to help it get rid of the TTP threat. South Asia expert Asfandyar Mir of the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) even argues that Pakistan has set in place “a broader pressure campaign to coerce the Taliban into reviewing and revoking its support for the TTP.”

“Pakistan shares a long border with landlocked Afghanistan,” said Mir in an analysis published recently by USIP. “(It) also supported and provided safe haven to the Taliban for nearly 20 years, all of which gives it unique leverage over the politics of Afghanistan. The main step to that end is Pakistan’s expulsion of refugees, which Kakar admitted is meant to pressure the Taliban. The other significant step Pakistan has taken is the scaling back of economic and trade ties to impose economic pain on the Taliban.”

As Afghanistan’s main trade route and significant export market, Pakistan’s actions, such as tightening trade rules, imposing higher bank guarantees, and imposing duties on certain imports, are affecting the Taliban’s revenue, which heavily relies on customs earnings, Mir said. The deliberate slowdown of Afghanistan-bound containers at Pakistani ports, as reported by the Taliban, adds to the economic measures being taken, he noted as well.

These days, the trade volume between landlocked Afghanistan and its southern neighbor has also been largely influenced by terrorist attacks in Pakistan that Islamabad insists the Afghan Taliban can help stop.

For sure, Pakistan is taking a bit of a hit, too, from the border closures. Torkham, for example, has increasingly played a vital role as a transit route for Pakistani goods, and has enabled the country to import and export commercial goods with landlocked Central Asian nations through Afghanistan.

Still, Afghanistan is hurting more. Pakistan, after all, takes 75 percent of its exports, with bilateral trade between the two countries reaching US$1.53 billion in 2022. That figure, however, is a considerable drop from 2010, when the comparative number was at US$2.5 billion.

Data gathered by the U.S.-based Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) show that in 2021, Afghanistan exported mainly raw cotton, coal briquettes, and grapes to Pakistan. Pakistan meanwhile exported rice, vegetable oils, and cement to Afghanistan during the same year.

“I think the Taliban, if they look at this issue rationally, would contend that their interests are served by having an open border because they value trade with Pakistan,” said Kugelman. “They (should) understand the positive impacts that these could have on the economy in Afghanistan.”

He also believes that it is going to be tough for Pakistan to agree to keep the borders open due to security concerns. Recent events like the refugee expulsion and increased worries about smuggling make things more complicated, Kugelman pointed out.

“Finding a solution will take a long time, and right now, there’s little hope for positive changes, especially regarding keeping the border open or addressing the TTP problem,” he said. “The relationship between Pakistan and the Taliban doesn’t look promising, not just now but also in the coming months.”

In truth, Gulbat, a 45-year-old trader from Pakistan, rues that even seemingly minor issues, like the installation of a “Welcome to Pakistan” sign, can lead to the closure of the border. The small-time businessman, who uses only one name, said that such a situation is unfair for traders like him.

“All the money we hope to earn from this work ends up being wasted when we have to stand at the closed border for days,” said Gulbat. “Even when the border reopens, it takes days for the crowd to disperse. This is our only source of income, and we plead with the governments of both countries to address the issue instead of resorting to closures.” ◉