|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This article is the last in a 10-part series collectively themed “Fostering Democracy Movements,” an Asia Democracy Network special 10th anniversary report produced by the Asia Democracy Chronicles. The release of this series is also in commemoration of Human Rights Day on December 10, 2023. The entire report can be downloaded here.

Just 10 years ago, Asia was awash in optimism, with headlines invariably proclaiming that “East Asia – even China – will be democratic in just a generation.” Today predictions about the region’s future are more tempered, if not grim.

The prospects (and even the viability) of truly open and responsive democratic societies in Asia’s future are being called into question by a compounding socioeconomic and political crisis, with weather extremes and violence growing by the minute.

Yet, for the first time in years, the democratic spaces in the region, especially in South Asia, seem more likely to open than close, albeit by a tiny margin.

Despite the odds stacked against Asian peoples, the last decade also saw a growing and increasingly converging pushback against entrenching authoritarians. For many activists, today’s generation shows promise of helping transform the region.

The Myanmar military’s takeover in 2021 served as a crescendo in both the comeback of autocratization in the region and the burgeoning pro-democracy movements. Democratic declines in specific parts of Asia, including the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan a few months later and subsequent crackdowns in Hong Kong, Bangladesh, and Thailand, put a spotlight on the fragility of fledgling democracies in the region.

| Democratic spaces at risk |

|

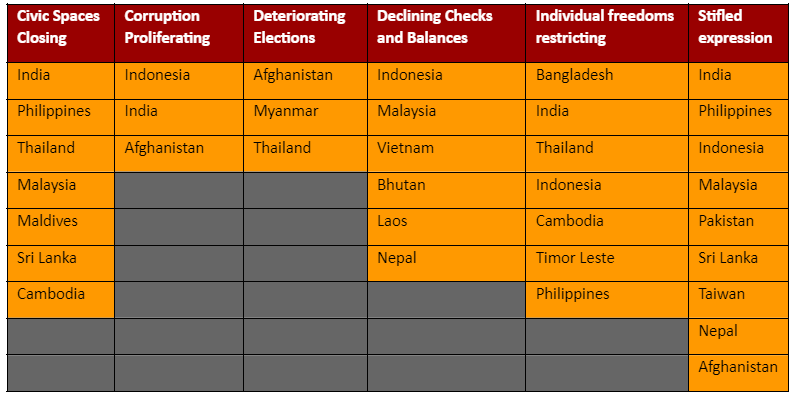

| Table 1: List of countries that are at risk of declining freedoms by category compared to previous years based on V-Dem’s assessment |

| Source: Democratic Space Barometer |

With Bhutan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, India, and even Japan and Taiwan at a moderate to elevated risk of adverse regime changes on the horizon, the future of democracy in the region is facing an uphill battle, to say the least.

The bad news

Based on data collected by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), 24 Asian countries had the most complete information, rendering them ready for comparison: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Vietnam.

| Likelihood of autocrats proliferating |

| Graph 1: Eight countries have a 10 percent or higher chance of experiencing a worse regime in the near future, excluding already closed autocracies. Note: Move the cursor across the graph to view specific country data. |

| Source: Adverse Regime Transition Risk 2022-2023, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) |

| Trajectory of democratic reform: Philippine Case |

| Graph 2: The Philippines is an example of a country in Asia that is less likely to shift to authoritarianism. A computation of its compounded annual growth rate of V-Dem scores from 2012 to 2023 shows that if democratic reforms in the country continue along the same path as seen in the last three years, those reforms will plateau at best in the next three to 10 years. |

The remaining half have improved – but then they are mostly closed autocracies, to begin with.

A closer scrutiny of the outlook suggests a further decoupling of different aspects of democratization, with countries like India highly likely to worsen in areas such as individual rights, civil society, and corruption despite an increased likelihood of electoral and governmental reforms. Indonesia and the Philippines, meanwhile, are consistently at risk of worsening in all aspects.

| Potential threats to democracy |

| Graph 3: The decline in electoral integrity, the erosion of socioeconomic rights, and the closure of civic spaces in specific parts of Asia are threats to democracy in more than half of the region. Note: The graph measures the probability of opening or closing of six democratic spaces: Informational (access to information and media freedom); Individual (enjoyment of individual freedoms); Governing (government checks and balances); Electoral (the ability of citizens to hold their government accountable through free and fair elections); Economic (public corruption); and Associational (freedom to associate with civil society). |

| Source: Democratic Space Barometer, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem). |

The year 2024 will be the biggest election year in history, as half the world’s population will beeline to vote, including those in nine countries in Asia. While the outcomes of elections in Sri Lanka and Bhutan remain unclear, it is widely anticipated that increasingly autocratic parties will maintain power in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. In fact, benchmarks suggest that even in the worst-case scenarios, a plateauing is more likely in most countries – increasingly stable, for better or for worse.

Growing pressures from geopolitical tensions, shifting norms around climate action, and lingering impacts of sticky inflation are some of the most imminent factors that can influence the upcoming polls. But a surging trend of pro-democracy movements, increasingly converging around Asia’s youth, is vying to shape the region’s future.

People-powered retooling

In both old and contemporary Asia, resistance against tyrants has been the best way to learn about democracy. By observing trends in protest movements, scholars are putting forth a theory regarding a “new democracy” and proposing a shift away from “benchmark liberalisms.” Experts also propose de-centering the focus of the pro-democracy struggle from self-aggrandizing dictators to a systems-thinking approach, drawing inspiration from emerging climate movements.

And that’s been the case for years in actual movements across Asia.

Most protests over the last three years have encompassed more than one issue such as human rights violations or climate change impacts. The convergence among movements, simultaneously for survival and progress, is in part due to autocrats’ blanket approach to stifling critics. With a growing recognition of multilayered crises bursting from a system-level flaw, especially since the pandemic, intersectional and intercommunity activism is on the rise in Asia.

This has been more pronounced with climate activists taking up the cudgels for civil and political rights and, in recent years, socioeconomic rights of Indigenous peoples and farmers in their advocacy. Insights on “false climate solutions” to delay climate action also foster a common understanding of the dangers of tokenism, greenwashing, and co-option among movements. A new wave of unions carrying intersectional slogans of digital rights, just energy transition, and decolonization are also burgeoning.

That wave bears a youthful face. Indeed, there has been a growing recognition of the youth as the rallying point of activism in Asia. New student and youth activism in several nations or regions — such as Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand — has captured national and international political interest.

A generation born into crisis after crisis, one that is increasingly militant yet methodologically pragmatic, has emerged as the driver of converging struggles. In Thailand, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Hong Kong, youth movements have combined both electoral parliaments and the streets to push for democratic reforms — balancing immediate and long-term goals. In Myanmar, the youth are at the forefront of an increasingly successful civil war to dispel a brutal regime.

In addition, across Asia, new protest centers outside the cities are emerging, especially in South Asia and Myanmar. National minorities of Assam, Manipur, Jammu and Kashmir, and Nagaland in India, and Balochistan in Pakistan, Sri Lanka’s Tamils, and, to some extent, West Papua in Indonesia, are revving up calls for self-determination, energized by, while pushing back against, autocratic repression and climate emergencies.

Indigenous women’s groups are growing and strengthening across Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka as they fight for intersectional rights. In the Philippines, Thailand, and Japan, LGBTQIA+ youth activists are lending their platforms to interconnected issues of repression, democracy, and the environment.

Equitable representation is now at the center of electoral reforms in the region. In Malaysia, an ambitious electoral reform toward a fully proportional representation via a compensatory mixed system is being slated for 2028’s general election. In Pakistan, trans activists have managed to reverse a dangerous Shariah court decision that would have posed greater risks to the well-being of this sector of society.

Speaking up, calling out

Freedom of expression continues to be one of the main targets of autocracies have focused on repressing across the board. Even in countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, where independent media are present, albeit not without their respective challenges, the worsening political climate has been encouraging self-censorship and stifling free criticism.

But there has been a growing consensus as well that a sustained pushback against increasingly severe and codified suppression of dissent and media freedom is a major factor in preventing civic spaces from shrinking further and reversing that tide.

The emergence of community and alternative media as supplemental information channels, increasingly tied with social movements, also points to much-needed reforms in the Fourth Estate. Ironically, attacks and weaponized laws leveled at the media institutions in recent years are now pushing toward a convergence in pushing back against authoritarians.

Moreover, the digital space as a new arena to contest power is becoming the norm among movements, especially since the pandemic. Repressive laws that encroach on privacy, deliberately target activists and opposition, and selectively punish critics have been a new mobilizing force in the last three years.

Weaponized disinformation and digital repression continue to erode democratic politics, both maintaining authoritarian regimes in power and contaminating the information environment in democracies. But digitalization has also incubated new types of movements, now more transnational than ever, and engaged the electorate even between elections.

The emergence of transnational youth movements like the Milk Tea Alliance has both reinforced and expanded a systems-thinking imagination among the population – now with instantaneous oversight of atrocities happening miles away.

In today’s age of disinformation where truth bends to power, history is being rewritten to retrofit autocratic values. Full histories of genocides are being glossed over, if not erased, especially for the peoples of West Papua, West Bengal, and Manipur in India, Mindanao in the Philippines, Myanmar, and, more recently, Palestine.

The rampant historical revisionism, evidenced by the swift return of dictators’ families to power in Southeast Asia and unpunished war crimes, is a long-term threat to democracy.

The past few years have indeed cast a daunting shadow over the region, with forces of autocracy and repression intensifying their grip. Yet, there is a strong beacon of hope emerging from the indomitable will of the people.

The youth of Asia, born into an era of tumult and transformation, have emerged as the vanguard of change, embodying a blend of militant fervor and pragmatic methodology. Their voices, echoing through the corridors of power and the digital expanse, are calling for a new era of democratic engagement.

Arming today’s youth with the vibrant history and legacy of Asian struggles against dictatorships and colonialism is thus one of the vital safeguards toward a more democratic future in the region. Building resilient and inclusive movements, with sentries at the watchtower and empowered peoples calling state authorities to account, is also essential also to charting a course for democracy in the region.

The future of democracy in Asia, while uncertain, will ultimately not be told through the whims of autocrats or the vagaries of political crises. It is, and always will be, in the hands of its people – determined, resilient, and unyielding in their quest for a brighter tomorrow. ◉