|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It’s a rainy early morning, and a motley crew has gathered at a public cemetery in Novaliches, in one of Metro Manila’s major cities. A priest, a church coordinator, two photographers, a team from a funeral home, three undertakers, and a family have come together to remove the remains of a man from one of the so-called “apartments,” the aboveground, low-cost final resting place for the poorest of the poor in the Philippines’ national capital region.

A young man has been trying in vain to separate the coffin and human remains on the fourth floor of the “apartment” for the last several minutes, with little success.

“Just get inside, that’s where you’ll end up anyway,” says one of his co-workers, teasing him.

Perhaps gallows humor helps, because after the young undertaker heaves his body inside the vault, heaps of bones, flesh, and clothes are extracted from the apartment. These are dropped on a stretcher held aloft by Roman Catholic priest Flaviano “Flavie” Villanueva and three other men.

Church worker Randy delos Santos hands the undertaker a big flashlight. “Use this, please,” he says, “to make sure everything has been collected.”

Delos Santos is right: there is a wayward finger, which is retrieved and placed in the hearse. The vault gets checked and rechecked, and then Fr. Villanueva gathers the family of the deceased and leads them in the rites for the dead.

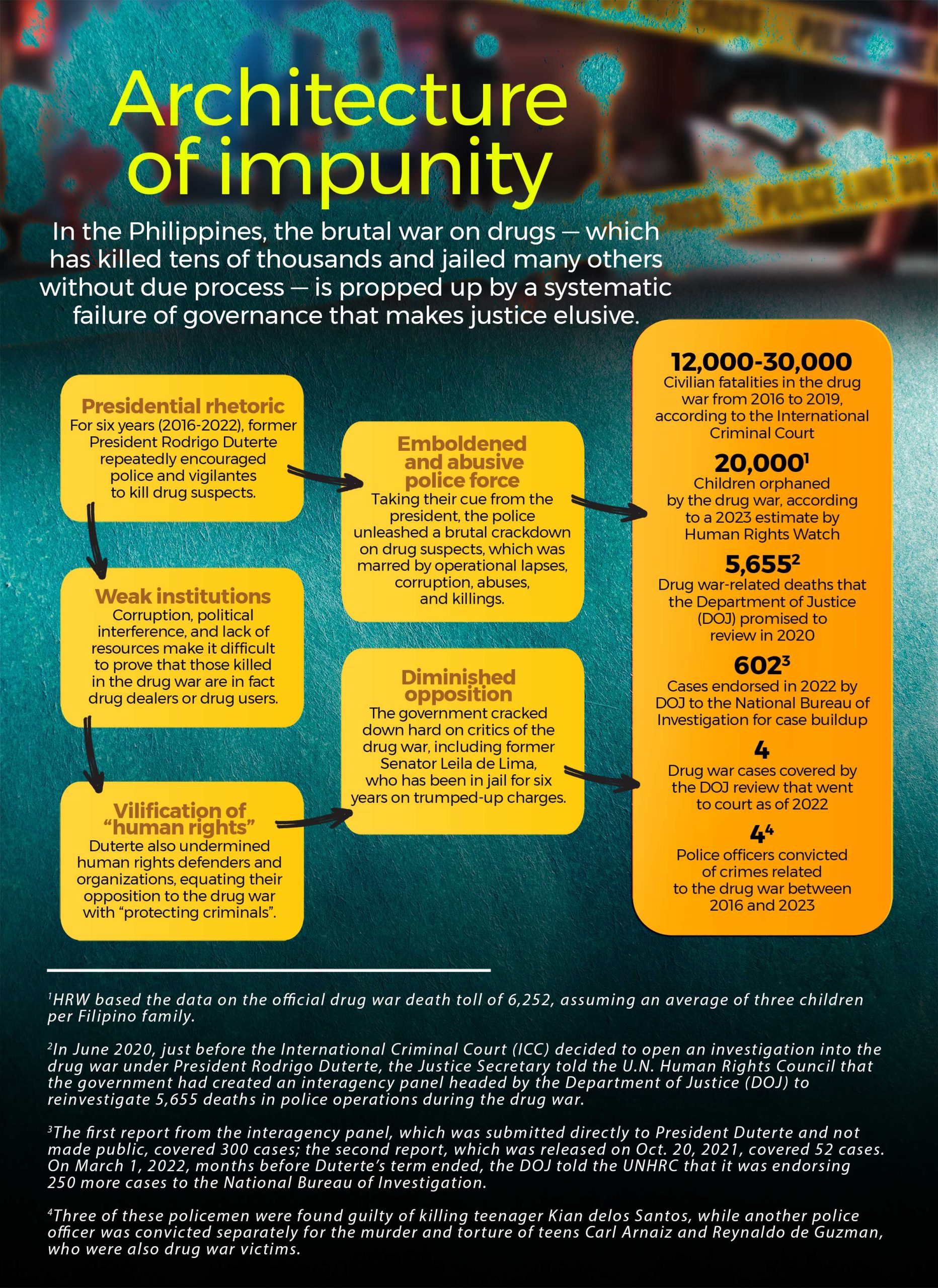

This is the 83rd exhumation by Villanueva’s team of the remains of victims of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s war against drugs. The brutal campaign is estimated to have killed 12,000 to 30,000 people during Duterte’s six-year term, according to the International Criminal Court (ICC), which has restarted an official probe on the matter. Meanwhile, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) pegs the death toll at 6,252 covering the period July 1, 2016 to May 31, 2022.

The numbers may vary, but one thing is sure: the bulk of those killed were male breadwinners who barely made enough to survive, and whose families now cannot afford a decent burial spot, much less an autopsy to establish how they died. According to the police, most of them fought back — “nanlaban” — which is why they ended up dead. Nearly all of those killed did not undergo autopsies — and therefore there was no further investigation — because their death certificates were incomplete or cited common illnesses like pneumonia or heart attack as cause of death. There were also cases where no death certificate was issued at all.

The exhumation done by Villanueva’s team is part of Project Arise, which the priest had started in 2021, in large part to ensure that the real manner of death of those killed in Duterte’s anti-drug war is properly recorded. Says delos Santos, whose 17-year-old nephew Kian had been among those shot dead during Duterte’s drug war: “This is the benefit of Project Arise: lies are corrected. The documents say they died of illnesses, but Dr. Fortun’s autopsy reveals a hole in the head.”

The dead tell tales

Dr. Raquel Fortun is one of the country’s only two forensic pathologists. Working pro bono, she receives the remains exhumed by Villanueva’s team, examines them, and then writes up an official report on how the victims died.

In her initial report after examining 47 remains, Fortun noted that at least seven who died of violent causes had certificates citing natural causes, such as pneumonia, sepsis, heart attack, and hypertension. She reported retrieving bullets from dead bodies despite previous autopsies. Some death certificates were also marked “for burial purposes only,” 26 had incomplete death certificates, and one had none.

Fortun pointed out that most of the death certificates were not even completely filled out, that police reports were unclear, and the crime scene photos, grainy.

In examining the teeth of the deceased, she deduced that they were so poor they could not afford basic dental care; most of them had bad teeth and very few had dental work.

Fortun had also examined the remains of delos Santos’s nephew Kian, even though at least two autopsies had already been done before he was buried. Kian was killed by policemen during an anti-drug operation in Caloocan City, in northern Metro Manila, on Aug. 16, 2017. The police said that the high school student had shot at them, prompting them to fire back. But witnesses said Kian, who was heard begging for his life, was dragged to an alley and shot, execution-style.

Kian’s remains were among those exhumed under Project Arise in August 2022. In her report months later, Dr. Fortun revealed what the previous autopsies – prompted by a public outcry over the minor’s death — missed: there was a third bullet lodged in Kian’s neck.

“If they had seen that bullet previously and examined it, maybe it would turn out that it wasn’t just one person who shot the child,” Delos Santos says. A police officer “was judged to be the killer because his bullets matched (those found in Kian’s body).”

Although evidence presented at the trial pointed to Police Staff Sergeant Arnel Oares as the sole killer of the teenager, a local court ruled the crime as a conspiracy, saying “the three accused all acted in furtherance of their common design and purpose to kill the victim.” Along with Oares, Patrolmen Jeremias Pereda and Jerwin Cruz were declared guilty of killing Kian delos Santos. In November 2018, the three were sentenced to up to 40 years in prison with no possibility of parole. They were the first to be tried and sentenced in connection with Duterte’s war against drugs.

Aside from being exhumed and examined, the remains handled by Project Arise are given a proper burial. From Dr. Fortun’s laboratory, they are collected by a funeral parlor and cremated. A mass is said, and the urns are handed over to their loved ones.

Says Fr. Villanueva: “If we don’t do this, it’s impossible for the families to heal because at the back of their minds is the guilt that they were unable to provide a decent final resting place for those they had lost.”

Two years ago, the widow of a drug-war victim had told him that the remains of her husband could no longer be found. It turned out that the apartment’s lease had run out, and the contents were discarded in a mass grave. So began Project Arise.

“I said not one less,” says the priest. “We have to respond to this urgent need so that all those who want to claim the remains of their loved ones can do so.”

Killings continue

Duterte’s violent war on drugs was initially pegged on his government’s 2016 estimate that the Philippines had three to four million drug users. In March 2019, Duterte increased that number to seven to eight million. In October that same year, the Dangerous Drugs Board claimed that the drug-user figure had declined sharply, to 1.67 million.

By the end of Duterte’s term, PDEA reported having seized PHP 89.79 billion (US$1.45 billion at current exchange rates) worth of illegal drugs and equipment, of which PHP 77 billion (US$1.37 billion) covered methamphetamine hydrochloride or “shabu,” known as “poor man’s cocaine,” because it is commonly consumed by low-income users.

PDEA also claimed to have arrested a total of 15,096 “high value targets,” including 6,768 netted under “high-impact operations” between July 1, 2016 and April 30, 2022. It also reported arresting 800 “drug group leaders and members.”

In May 2022, Duterte’s successor, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., admitted that there had been abuses in the implementation of anti-drug policies by the previous regime. “Perhaps, in my view, what happened in the previous administration was we focused very much on enforcement,” Marcos Jr. said, “and because of that, it could be said that there were abuses by certain elements in the government that have caused concerns from many quarters about the human rights situation of the Philippines.”

Despite this, Marcos Jr. has ruled that his government will not cooperate with the ICC, echoing his predecessor’s stance that the organization has no jurisdiction over the Philippines.

In his 2023 State of the Nation Address, Marcos Jr. said that his government’s drug-war program was “now geared toward community-based treatment, rehabilitations, education, and reintegration.”

According to the 2023 Human Rights Watch (HRW) Report, “the unlawful use of force by the police and government agents (has) continued” under the Marcos Jr. government. The report cited data from Dahas, a research program run by the Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines.

Dahas reports that as of June 30, 2023, a year into Marcos Jr.’s term, a total of 342 have been killed by state actors in connection with illegal drugs. This is higher than the 302 reported in the last year of the Duterte administration.

The first of four photos shows Randy delos Santos, uncle of slain 17-year-old drug war victim Kian delos Santos, and Catholic priest Flavie Villanueva as they prepare for their 83rd exhumation of drug war victims, whose leases on their “apartment” tombs have lapsed after five years. The second and third photos show Villanueva praying over the tomb, before undertakers crack open the apartment to extract the victims’ bones (fourth photo). (Photos: Jaileen Jimeno)

“Nothing has changed,” laments Villanueva. “The killings continue the same way as they did during Duterte’s time. I say this because no one has been tried and apprehended (for such killings yet under the current administration).”

He adds that while Marcos Jr. has categorically stated that he is against a violent drug policy, the killings are still brazen, blatant, and an overkill. Unfortunately, too, that could mean even more exhumations, examinations, and proper burials ahead for Project Arise.

Award-winning photojournalist Raffy Lerma, formerly of the broadsheet Philippine Daily Inquirer, says of the project: “This is part of the process of finding the truth. We are still seeking accountability. Hopefully, things will come full circle.”

His former job had Lerma documenting grisly drug-war deaths on a nightly basis. These days, while photography is still his main job, Lerma gets invited to speak about his drug-war work in the Philippines and abroad. Yet whenever Fr. Villanueva calls for help in an exhumation, he shows up.

Lerma is confident that a reexamination of the remains will reveal how the victims really died. He notes that crime-scene operatives work too quickly on crime scenes involving the poor. “When the victims are poor, the crime scene processing is quick,” he says. “Ten minutes and it’s done. When it rains, it becomes even quicker.”

Lerma says that the pictures he and his colleagues took, and those taken by the victims’ relatives, will be helpful in the future.

“When (those photos are) pieced together, maybe we will come up with a complete picture,” he says.

That, for now, is what Project Arise hopes to provide: a complete picture for some of the deaths in the Philippines’ war against drugs. Toward that end, the unearthed corpses speak eloquently. ◉