|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

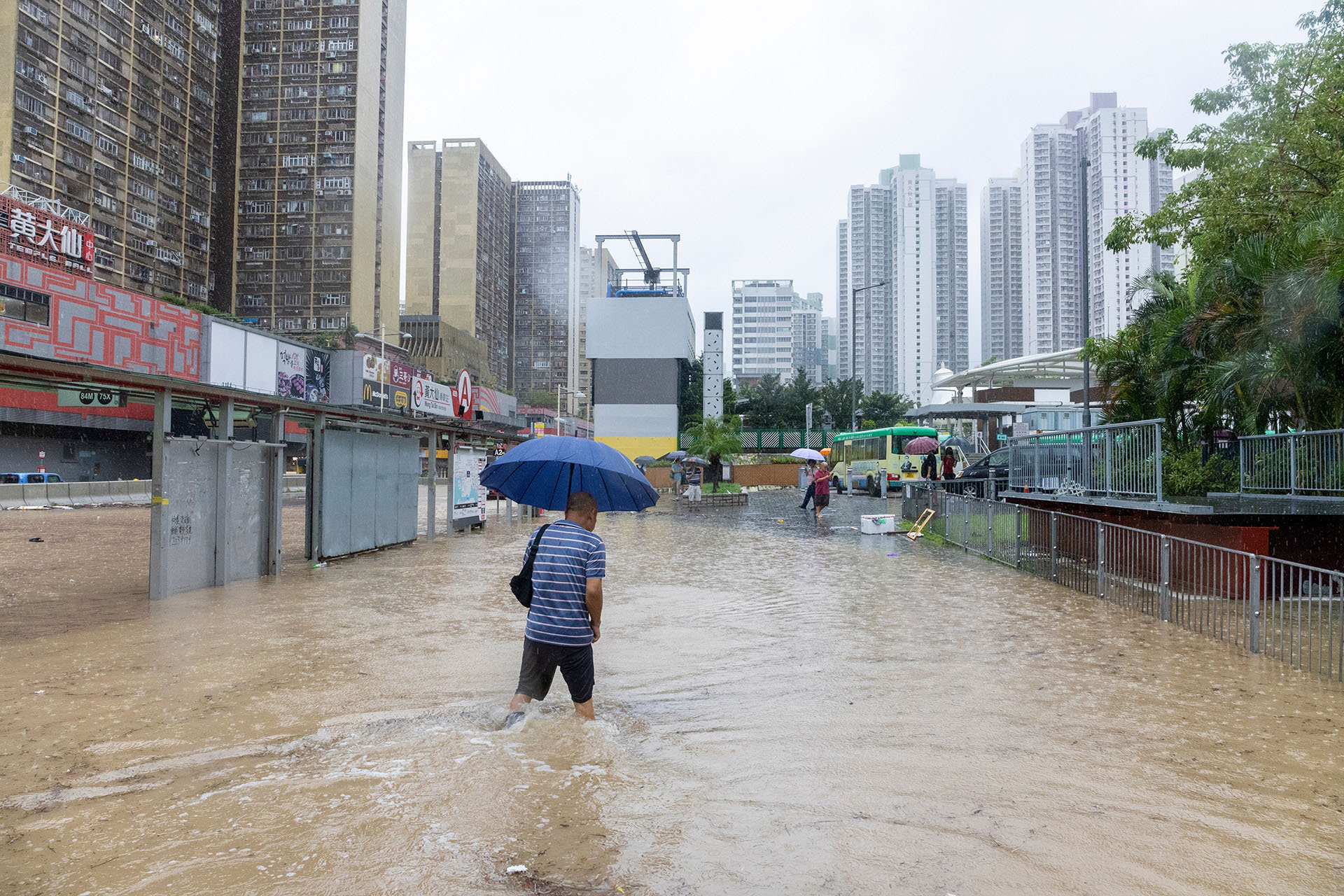

The photos and videos coming out of Hong Kong were shocking. Roads had turned into rivers across the city in less than two hours, and one viral video on social media even showed water cascading down the MTR subway station in Wong Tai Sin in New Kowloon.

As a Hong Kong expat in London, my first instinct was to question the authenticity of what I was seeing on my laptop, as the scenes were staggering. But obtaining genuine insights into any situation in Hong Kong has grown difficult due to tightened media control under the three-year-old national security law (NSL), diminishing transparency in information and news. Still, I knew that Hong Kong was no stranger to heavy rain and typhoons in summer, but its well-developed infrastructure and reliable drainage system was still more than capable of shielding it from such harsh weather events.

That is, until last Sept. 8. According to media reports, the floods had been caused by the heaviest rainfall Hong Kong had experienced since 1883, when the city began keeping weather records.

The deluge caused chaos across the city and led to at least two deaths and scores of injuries. It also exposed the unpreparedness of today’s Hong Kong for extreme climate situations. The disaster raised questions about the government’s capabilities to handle such emergencies, and drew attention to the governance quality practised by the city’s current authorities after the draconian NSL was set in place in 2020.

The deluge caused chaos across the city and led to at least two deaths and scores of injuries. It also exposed the unpreparedness of today’s Hong Kong for extreme climate situations. The disaster raised questions about the government’s capabilities to handle such emergencies, and drew attention to the governance quality practised by the city’s current authorities after the draconian NSL was set in place in 2020.

The heavy rain had begun hours before midnight of Sept. 7, prompting the Hong Kong Observatory to issue a Red Rainstorm signal at 9:50 p.m. It subsequently raised the rainstorm warning to the highest level, Black, at 11 p.m. Based on the official rainstorm warning system, Black meant a likelihood that “very heavy rainfall” would continue over the city, and “exceeding 70 millimeters in an hour.”

The Observatory later said that between 11 p.m. and midnight of Sept. 7, the amount of rain that fell on Hong Kong had reached 158.1 millimeters. By the next day, the floodwater in some parts of the city was waist-deep.

According to the Observatory, the city’s rainstorm warning system is “designed to alert the public about the occurrence of heavy rain, which is likely to bring about major disruptions, and to ensure a state of readiness within the essential services to deal with emergencies.” The Black warning, however, was issued when some people who needed to wake up early for school or work the next day were already asleep.

The city’s residents would later note that there was a glaring absence of additional warnings from the government. Many Hong Kongers had at first believed it would be another heavy rain like those they had usually seen in the past; they did not expect that it would turn into an exceptionally severe deluge, until they saw many roads and streets under water and some MTR stations had already been forced to close.

The government issued press releases, but despite the widespread and unprecedented flooding, no government official appeared before the public or provided further details and updates about the flooding that lasted for hours. Worse, authorities did not announce school suspension and work advisories until 5:34 a.m., six hours after water began rising in the streets. By then, some people were already out and deep in the wet mayhem, while most parts of the city were paralyzed by the floods.

This lack of prompt response brought the government under substantial public criticism, and raised more questions about its emergency response capabilities. The public had every reason to feel angry, especially in light of the government’s continuous assurances to citizens in recent years about its commitment to enhancing governance performance.

Rubber-stamp legislature

Following the imposition of the NSL and an overhaul of the election system, the Hong Kong government has been projecting an image of efficiency. It has vowed to improve living conditions and boost the economy so as to prove that its “improved” electoral system, which prohibits pro-democracy candidates and transforms the city’s parliament into a mere formality, is much better than the previous one. It also aims to demonstrate that “the model of democracy with Chinese characteristics” surpasses the Western-style democracy that Hong Kong people have been longing for.

Two years on, however, the Hong Kong government appears to have fallen short of its aspirations. There is no tangible improvement in its performance. Instead, there have been increasing doubts about the government’s administrative competence.

One prominent factor contributing to the decline in the government’s performance is the lack of effective mechanisms to hold it accountable. That is no thanks in part to the Legislative Council election reform in 2021, which barred all pro-democracy candidates from running, thereby effectively enabling the government to pass any bill it wishes. Just this August, local newspaper Ming Pao found that between January and August 2023 almost 90% of the government bills were passed by a show of hands instead of formal voting. In addition, approximately two-thirds of the bills were passed when less than half of the members were present for voting.

The frequency of oral and written questions proposed by the councilors has markedly diminished as well compared to when pro-democracy politicians were an integral part of the Legislative Council. And when the Council no longer carries the function of checks and balances and is no longer a mirror of public opinion, government policies naturally become more prone to overlooking public sentiments, and the measures introduced are more likely to stray from people’s desires.

Today this level of scrutiny no longer seems attainable. Earlier this year, as the city emerged from the three-year-long grip of COVID-19, which led to more than 13,400 deaths in Hong Kong, some health experts demanded an independent inquiry into the government’s handling of the pandemic. But Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee rebuffed these calls, arguing that since COVID-19 was a novel disease, “there’s never a best practice or best way to deal with such an issue.”

Facing criticism over its handling of the recent floods, government authorities resorted to a similar excuse, labeling the Sept. 7-8 rainstorm as a “once-in-500-years event” and that the flooding was difficult to avert. A week later, when another heavy rainstorm caused a deluge across the city, acting Director of Drainage Services Chui Si-kay used the phrase “water accumulation” to characterize the flooding, attracting widespread criticism for seemingly understating its severity.

Gagged public

Indeed, it has become increasingly commonplace to witness officials resorting to unpersuasive excuses to evade their responsibilities. That they are getting away with it so easily can be traced to Hong Kong’s prevailing political climate, where people have largely become reluctant to express their opinion.

After the crackdown on civil society with the national security law in 2021, all dissident voices have been virtually silenced. People are worried that commenting on public policies would be interpreted as a form of “soft resistance,” a term used by Beijing to describe the behaviors that focus on “disseminating disinformation, creating panic, maliciously attacking the SAR (Special Administrative Region) government and the central authorities and distorting the Basic Law.” In May 2023, several NGOs focusing on grassroots’ housing rights were criticized by the state media Wen Wei Po for “inciting citizens’ negative emotions against the government.”

It was out of sheer frustration that people ended up complaining over the government’s response to the floods. But the grumbling was decidedly low-key compared to pre-NSL times. To prevent being sucked into political strife or attracting the ire of authorities, many people simply avoid making suggestions to the government or commenting on public affairs. Public views are thus practically absent from governance, a situation that in turn is hindering the enhancement of governance quality. The government’s voice prevails unilaterally, leading to governance relying solely on the limited insights of those in power and their loyalists.

It’s a set-up that often yields disappointing results, even when the intentions are well-meaning. For example, following the first September floods, the government deployed the newly formed District Services and Community Care Teams to affected areas. The Chief Executive had put together these teams to bolster district-level efforts. But with the majority of Care Team members being pro-government affiliates, residents saw their actions as mere political gestures rather than genuine assistance. Some residents also told the media that the Care Teams distributed SIM cards when the phone and Internet services were inaccessible due to the flooding, raising doubts about teams’ capability to provide effective help.

Regrettably, the government seems set to persist in imposing an authoritarian regime in Hong Kong, and stifling diverse voices and leaning on “patriots” for governance. For residents of the city, that means they will have to rely mostly on themselves in dealing with challenges that yet another flood or other extreme event may bring. ◉

Andrew Shum is a Hong Kong human-rights activist based in the United Kingdom. He was the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union and the cofounder of Civil Rights Observer. Both groups disbanded due to political pressure.