|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A

t Singapore’s teeming hawker centers, there are always newspaper vending machines that never seem to go empty. That’s not because media companies are quick to refill them. Rather, it’s because few Singaporeans are buying local papers these days.

According to official data, 97.1 percent of Singaporeans 15 years old and over are literate, so the inability to read can’t be the reason why the newspapers aren’t getting sold. But with the prevalence of technology nowadays, people are moving to online media rather than buying hard copies; Singaporeans may just be following the trend.

And yet, Singapore Press Holdings Media still found it necessary to inflate the daily circulation numbers of its titles such as The Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao by between 85,000 and 95,000, going through the trouble of printing the papers, counting them for circulation, and then destroying them.

Maybe that’s partly why Singaporeans aren’t reading local papers. If news outlets can lie about basic information such as their circulation numbers to advertisers and stakeholders, what else could they be lying about?

Most probably, however, there is little they can lie about, because they end up not saying much anyway.

In Singapore, no journalist and media worker from the mainstream press get killed or detained despite the country’s authoritarian rule of law. The reason is simple: editors, journalists, media workers, and even most of the rest of Singaporeans practice a high level of self-censorship.

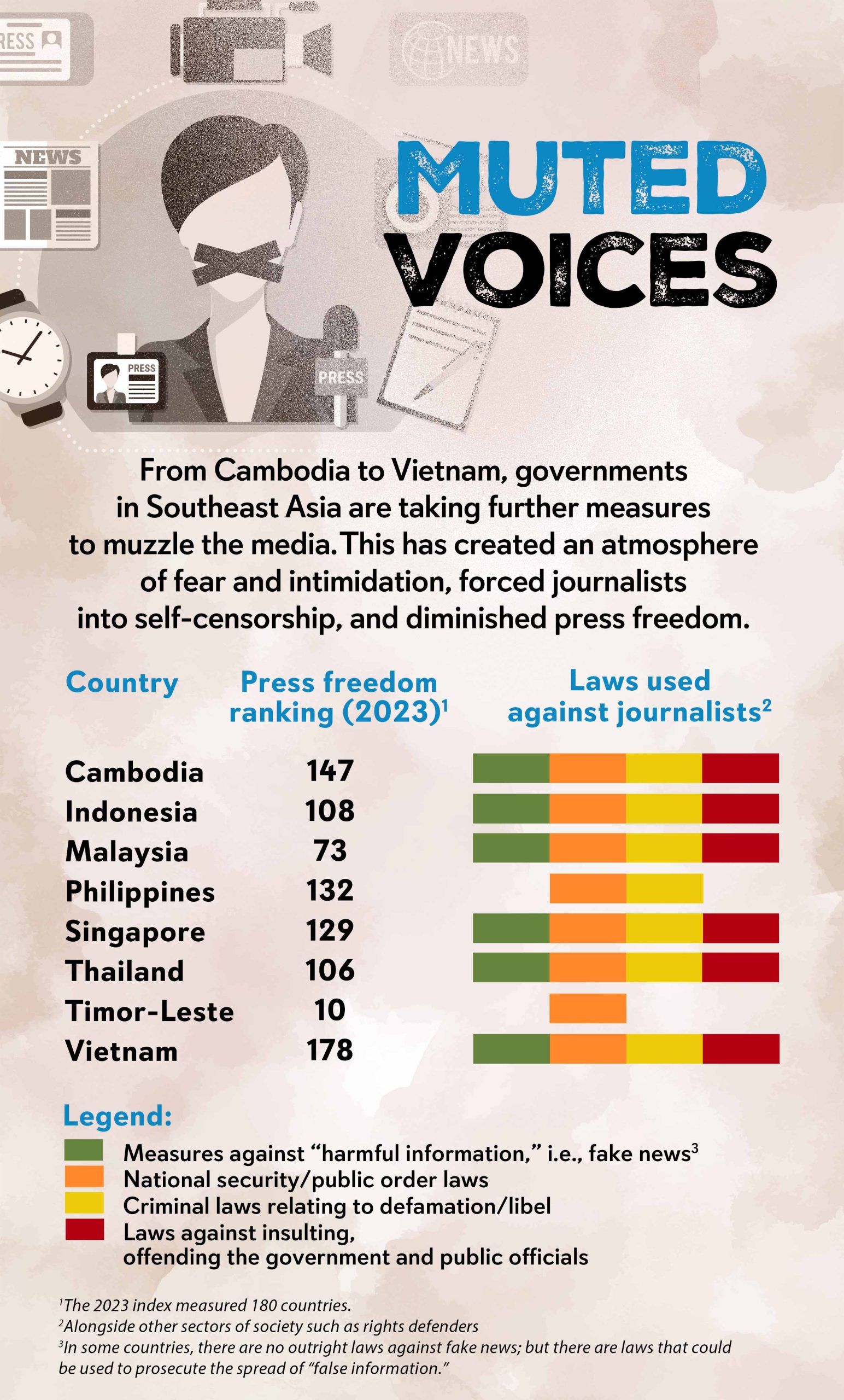

The international media watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF) says of Singapore: “Singapore boasts of being a model of economic development but it is an example of what not to be in regard to freedom of the press, which is almost non-existent.”

In RSF’s latest World Press Freedom Index, Singapore has risen to 129 out of 180 countries — a leap from its rank of 160 in 2021. That’s still far from being halfway up the list, though, and Singapore has been colored black on the index map since 2020, meaning the situation remains “very bad.”

Avoiding trouble

Supposedly, the higher one’s rank, the freer its press, which indicates there is supposed to have been an improvement. But Singaporean journalists themselves don’t seem to feel any change.

“Of course I have to practice self-censorship,” says one Singaporean journalist. “This is why with the current government, no Singaporean journalist will ever win the Pulitzer Prize. If any of us want to write a decent opinion piece, we will have to … explain our motives. They will assume that we are politically motivated, and we may lose our jobs or not have our contracts renewed.

In-depth or investigative articles probing into sensitive issues are out of the question. “We are not encouraged to write any investigative journalistic articles, too. Those articles will not be published, and we will not get a positive appraisal for bonuses,” adds the journalist.

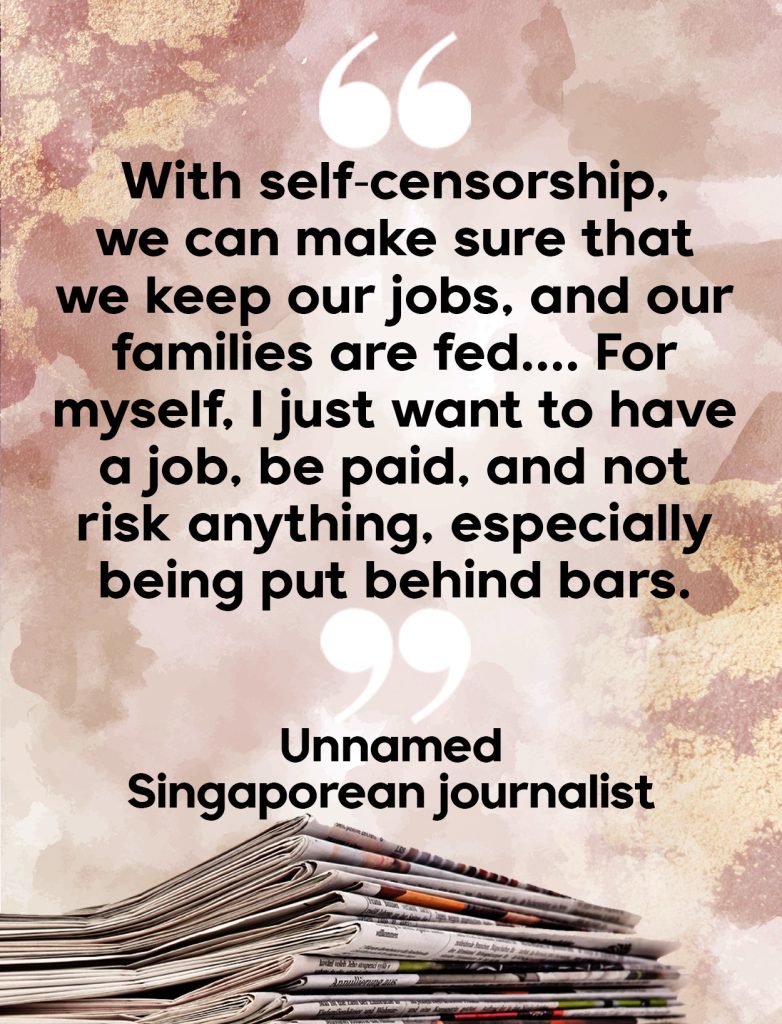

“With self-censorship, we can make sure that we keep our jobs, and our families are fed,” says another journalist. “Without self-censorship, we will risk being one of the many unemployed or underemployed in Singapore. For myself, I just want to have a job, be paid, and not risk anything, especially being put behind bars.”

As a result, mainstream journalists stick only to what is “safe,” which in Singapore translates to mainly news promoting the government’s standpoint. It also means little or no coverage of protests or grievances aired by the public.

Last year, for example, the government’s Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme angered Singaporeans who were staying in the prime minister’s Ang Mo Kio constituency. The residents there had been forced to relocate their homes because of the scheme. Yet not only did the government not compensate the people, it demanded that they pay for the relocation of their public housing estate to a decidedly less convenient place. That had the residents seething, as many of them were retirees on tight budgets, which certainly did not include unplanned payments to the government. Yet Singapore’s mainstream media did not pick up the news until social media went viral about it, and videos of angry residents quarreling with government officials had already surfaced online.

Singapore does have alternative media – also known as the pool where Singaporean authorities fish journalists from to throw behind bars. Among them was Australian citizen Ai Takagi, co-founder of The Real Singapore (TRS), a socio-political website that was shut down by its editors in May 2015 after the Media Development Authority suspended their license to operate the site and ordered them to take it offline. By the next year, the then pregnant Takagi was serving a 10-month jail sentence, having been found guilty of sedition for articles deemed to be fomenting enmity among the country’s ethnic communities. Her husband, a Singaporean, was later sentenced as well to prison, albeit for a shorter term of eight months.

Although Takagi pleaded guilty to the charges against her, she was quoted by the Australian press as saying that the TRS was “about citizen journalism so that people could air their views about all sorts of things… but it was painted like the whole website was pitting foreigners and Singaporeans against each other.”

Last year, Terry Xu, former editor of the shuttered The Online Citizen (TOC), was also jailed for three weeks over charges of defamation, stemming from his publication of a letter alleging corruption among state officials. In 2021, Xu and a TOC writer were ordered to pay Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong a total of SGD 210,000 (US$154,000) in connection with two separate defamation lawsuits Lee had filed against them. The lawsuits were triggered by a TOC article on a family property dispute involving the premier.

The Guardian, a U.K.-based publication, described TOC as being “known for its relatively liberal stance and for featuring criticisms of the authorities in the city-state.” Xu is now based in Taiwan, as is the revived The Online Citizen.

All whipped

In Singapore itself, the remaining alternative media are not those that go against the government, unlike similar operations in other countries. In fact, many if not all the alternative media in Singapore are pro-government. But questioning just one policy or not following government instructions could render an independent media publication an “alternative” outlet in the eyes of the authorities.

Either way, toeing the line also does not shield media organizations from sanctions if authorities think they have not followed the rules. In March last year, for instance, Mothership.SG had its press accreditation suspended for six months for publishing an infographic with details of the government Goods & Services Tax hike before the finance minister announced it officially during his budget speech.

Mothership’s experience seems to show that it is not only the media perceived to be non-supportive of the government that get the whip. The crucial question, though, is how and when that whip is used — and perhaps whether any whip should be employed at all.

In truth, the Singapore government has many whips, and these aren’t just for the media.

One is the amendment of the Penal Code in 2018, with the move coming after an estimated 6,000 Singaporeans gathered to voice their disapproval against changes made to the national pension scheme.

Under the law, Singaporeans are not allowed to engage in any act in or outside the country that may be deemed prejudicial to public safety. The terms “public safety” and “national threat,” however, are vague and open to all kinds of interpretation.

In 2017, before the amendment was even in force, a Singaporean human rights defender was invited to Malaysia to talk about her experiences of solitary confinement in Singapore. The Singapore government demanded the deportation of the human rights defender to Singapore, citing “national threat” as justification.

There is also the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), which the government introduced in 2019. The law makes it illegal to “diminish public confidence in the performance of any duty or function of, or in the exercise of any power by, the Government, an Organ of State, a statutory board, or a part of the Government, an Organ of State or a statutory board.”

Under the POFMA, the Singapore government also has the right to demand media outfits to take down any article that the ruling political party is unhappy about. If the “offending” article is not removed within 24 hours, the organization will be liable to pay a fine not exceeding SGD 50,000 (US$36,600) or face imprisonment for up to three years, or both.

But even if Singapore’s mainstream media decided to break free of its fetters, it could all be for naught, with few Singaporeans still buying their papers. Reading about discriminatory or unfair government policies can just get one angry. That could lead to one deciding to do something, such as protesting on the streets or making videos online to raise awareness about such policies. But if one were to do that, one would run the risk of getting sacked, being interrogated by the police, or going bankrupt should one be slapped with a defamation lawsuit by a government official. Worse, he could get hauled into jail.

In Singapore, ignorance has truly become bliss. ◉

Han Hui Hui is a Singaporean blogger and human rights activist, who uses her blogs to raise awareness of specific public policies and human rights issues in her city-state. She is Singapore’s first Human Rights Fellow at the University of York in England, where she published her book Yearning For Justice: A Mother’s Musings To Her Future Child.