|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It was supposed to be just another day doing fieldwork for a story. Online media journalist Adel (not her real name) and a few other media people had gone to cover a land acquisition case then unfolding in Sari Rejo, a village in Medan in Indonesia’s province of North Sumatra. At the scene were members of the Indonesian air force who were having a heated discussion with several villagers — a confrontation that soon deteriorated into violence.

Adel and the other journalists were caught in the melee. According to Adel, who was then in her mid-20s, she had shown the air force personnel her press card. But she was still beaten up, leading to injuries that later landed her in the hospital, along with two male colleagues. Her working tools were also confiscated, and security personnel threatened to insert a club into her sensitive area.

That was seven years ago. But Adel, now an editor for another media outfit, said that while her physical injuries have healed, the incident has left her traumatized. She told ADC that she was even “afraid of seeing” any group of military men.

“I didn’t even want to see my brother who is with the army,” she said. “I didn’t want to talk to him whenever he was in uniform. Later, he understood and now he doesn’t wear it when he meets me.”

In many parts of Asia and beyond the region, journalists have come to accept threats to their life as par for the course in the line of duty. But while attacks on media personnel are less frequent in Indonesia compared to those in the likes of the Philippines, Cambodia, India, and Pakistan, indications are that journalists in the Southeast Asian country still face ever-increasing risks. That’s bad news especially for female Indonesian journalists, who already have to put up with various types of violence and abuse primarily because of their gender.

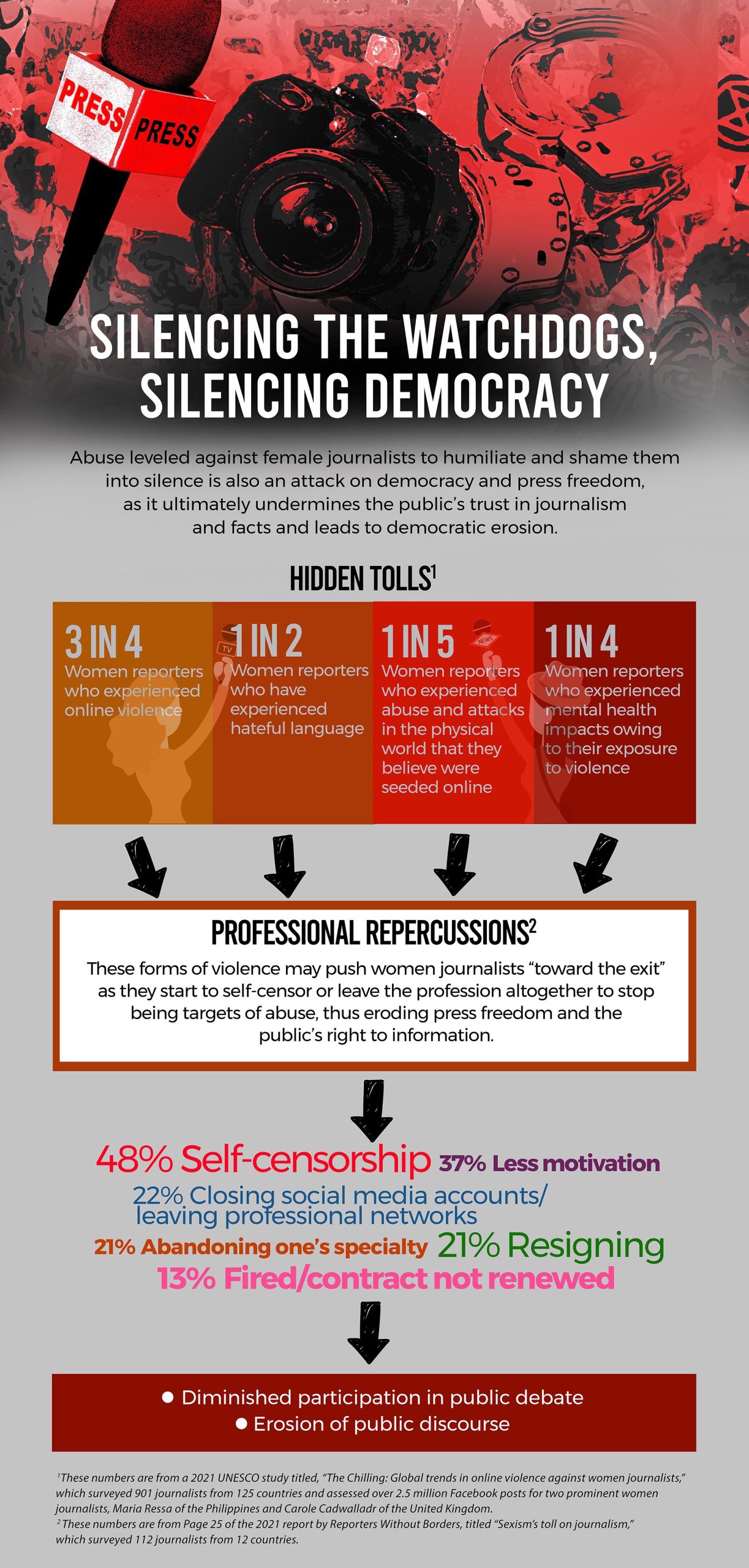

In a study released last year by the media research organization Pemantau Regulasi dan Regulator Media (PR2Media) based in Yogyakarta, 85.7% of the 1,256 Indonesian female journalists surveyed in 2021 said they had experienced violence during their journalistic career. “Of these,” said the study, “as many as 70.1% of the respondents had experienced violence in the digital domain as well as in the physical domain, 7.9% of respondents had experienced only violence in the digital domain (online), and 7.8% of respondents had experienced only violence in the physical domain (offline).”

The female factor

Interestingly, interviews conducted by the study’s researchers indicated that non-sexual violence experienced by the journalists were connected with their work, and specifically with the issues they were covering. By contrast, while the journalists said that the perpetrators of sexual violence were usually the sources they encountered as part of their job, the trigger was not the story they were doing, but simply because they were female.

In the case of Adel, she experienced not only physical violence because of what she and her colleagues were trying to cover, but also received a threat that was sexual in nature because of her gender.

P. Ginting, editor at the Nationwide Multimedia Group, noted: “Violence including sexual assault can occur anywhere. Women, including journalists, remain vulnerable to sexual harassment in the field and in the workplace, including the newsroom. However, this could be due to the behavior of ‘unscrupulous’ machos, who have a limited perspective on everything, including how they perceive women.”

But that “limited perspective” may in fact be widespread. In Indonesia’s patriarchal society, women are supposed to play supporting roles to men. This perception persists even though a woman may have already managed to achieve a significant position in the workplace or has stellar professional credentials. As Nani Afrida, chairperson of the Gender, Children and Marginalized Groups of the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI), put it, “(Violence) also happens to female journalists, a group that is socially and politically categorized as more empowered because of their profession and knowledge compared to Indonesian women in general.”

Researchers in the 2021 PR2Media study even observed, “As a result of their gender identity, female journalists experience violence in the digital domain more often than male journalists do, because female journalists are considered as objects of harassment or violence.”

The nature of their work also exposes journalists to more risks of violence because of the need to constantly engage with various types of people. For female journalists, such exposure means heightened risk of gender-related abuse.

The head of an online media outfit in Medan, for instance, told ADC that when she was still working as a TV reporter decades ago, her being female meant enduring such things as her office superiors’ rejection of her pieces, as well as verbal abuse and lewd comments from sources. She said that she was able to do her reporting duties even when faced with “unpleasant situations” largely because her cameraman would always be by her side.

Yet little has changed since; worse, there are signs that sexual violence has become so commonplace that female journalists now take them as a given in their work – as do their male colleagues, some of whom tell them to just grin and bear it. One online media journalist who was groped by an interviewee told academic Aderia of the University of Indonesia that her cameraman’s reaction was to say, “It’s just a common thing. Just ignore it. We have to get a story from him.”

“A world for men”

The journalist was among the seven women interviewed in depth by the scholar for a paper that was eventually published in July 2020 by the Jurnal Komunikasi Indonesia. Wrote Aderia in her paper: “Almost all interviewed female journalists were reluctant to report or process the harassment they experienced. They thought it was useless because the environment would just allow the incidents.”

She rued that fellow journalists, as well as “supervisors, even the female one, will not pay much attention to such issues. Fear to be considered weak or not tough, and fear of being blamed is the reason why female journalists do not report the harassment they encountered. Some even think it is their own fault to be a victim of harassment.”

That silence, however, may be mistaken as implicit tolerance, if not approval, for the acts of sexual violence and abuse. In a 2022 study by AJI and PR2Media, which released the findings earlier this year, 82.6% of the 852 female journalists surveyed said that they had experienced sexual violence throughout their media career. Body shaming and catcalling were the most common among the types of sexual violence experienced by the journalists, although many also said that they received explicit messages, audios, and videos, or were subjected to “unwanted sexual physical touches.” Nearly three percent said they were “forced to have sexual intercourse offline,” while 4.8% said they were “forced to touch or serve the perpetrator’s desires offline.”

But the perpetrators were apparently not only confined to people the journalists met outside of the newsroom or to anonymous trolls. Nearly 16% of the study’s respondents also named coworkers as being among the perpetrators of sexual violence, and 3.4% seniors at work.

An explanation for this is indicated in the 2021 study Women, Journalism, And Discrimination in Indonesia Digital Media by academics from the Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. The paper brought up the country’s patriarchal setup, while pointing out that “there are still many who think that journalism is a world for men.” The scholars also said that men far outnumber women in Indonesian media “because women are considered incapable and unsuitable for journalistic work, which is considered challenging and risky.”

AJI’s Nani Afrida said that it is sad that not all media organizations have a support system to prevent and deal with sexual violence. But she said that the year-old Law on the Crime of Sexual Violence (RUU-TPKS) could become a starting point in eradicating sexual violence in the media environment.

That is, if the law can get implemented at all. According to the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), there have already been cases involving sexual violence that were filed after the law was passed in 2022, but the legislation has yet to be applied to any of these because of the missing implementing rules and regulations. Complicating matters are the apparent lack of understanding of the law, as well as various obstacles to the needed cross-sectoral coordination in the integrated criminal justice system for handling such cases.

The offense of physical sexual violence is punishable by imprisonment for a maximum of 12 years and/or a fine of up to IDR 300 million (approximately US$20,500). Victims of sexual harassment meanwhile are granted legal protection under Articles 5 and 6 of the Law No. 31 of 2014, amending the Law No. 13 of 2006 on the Protection of Witnesses and Victims. But few file cases in court, with many preferring either to settle out of court or just keep silent.

For the serious assault suffered by Adel and her male colleague, support for their case came from media organizations including AJI, the Press Council, and the Indonesian Women Journalists Forum (FJPI). Two air force men were eventually sentenced to jail by a military court, but only for the violence done on one of the male journalists. The other one, a cameraman, also filed a complaint with the Medan Military Police, but it went nowhere. Adel opted out of any legal proceedings; she has declined to explain why. ◉

Nurni Sulaiman is a journalist based in Medan, Indonesia and has been actively writing for The Jakarta Post since 2007. She covers various issues, including refugee rights, inequality, gender, environment, bilateral and multilateral cooperation, culture, economy, and sports.