|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Last month, on Aug. 19, a Vietnamese man from Tuyen Quang province, located on the northeastern side of Vietnam, died at a police station in the neighboring Ha Giang province after being arrested two days earlier in the locality while settling a personal problem. He told his wife earlier that the police had beaten him during the questioning. The Ha Giang Police Department, on the other hand, said that he “committed suicide” by tying up his legs and hands and dipping his head into a water tank.

On Aug. 17, another man from Hai Phong, also located in northern Vietnam, was hospitalized and ended up in the coma after spending two days in police detention while under investigation for theft. His father told state media that his son’s face had bruises and looked pale, although he looked healthy at the time of his arrest.

On May 25, a man from Bu Dang District in southern Binh Phuoc Province was reported dead only a few hours after being held at a local police detention center. Bu Dang police in the southeast region of Vietnam previously detained him on suspicion of stealing electrical wires. The autopsy results showed that the deceased man had several bruises on his body. The authorities later announced that he tested positive for drugs and that his death resulted from “acute pulmonary edema,” a fluid buildup in a patient’s lungs. The local police department claimed the accusations that he was beaten to death by police officers were “groundless.”

The latest deaths and injuries recorded at Vietnamese police stations are tiny pieces of a big picture about the brutality committed by law enforcement officers. Most of the time, the police agencies shifted the blame to the detainees, claiming they “committed suicide” while in custody to justify these ambiguous deaths and shirk their responsibility. And since those alleged tortures were committed behind closed doors, there is no evidence to prove such allegations and hold the suspected police officers accountable.

Forced confessions, wrongful death sentence

The national police force, which remains under the official authority of Vietnam’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS), is adept at utilizing torture and physical coercion as a convenient tactic to speed up the crime investigation process. Such notorious practice has been carried out to extract forced confessions from alleged suspects and detainees.

Recently, the Vietnamese public was shocked by reports of the widespread use of violence under the country’s criminal justice system following the execution announcement of Nguyen Van Chuong, a wrongful death-row prisoner.

Chuong, a native of Hai Duong province in northern Vietnam, who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 2008, repeatedly pleaded not guilty. He said he was brutally tortured and intimidated by police officers to confess to the crimes he was being accused of. The investigative police agency of the city of Hai Phong concluded that Chuong killed a police officer in the city in 2007 in an attempt to steal his money so he could buy drugs. The evidence used to prosecute and convict him was entirely based on confessions taken under extreme duress.

During visits with his family, Chuong recounted his experience as a suspect under investigation at a Vietnamese police station. He told his father, Nguyen Truong Chinh, about the torture committed by police investigators to make him confess against his will. Chuong claimed the investigators tied his arms around the back of a chair and then used a wrench to hit his knees and ankles. On another occasion, the police clamped ballpoint pens between his fingers before pressing them hard.

Chinh informed Luat Khoa Magazine in an interview about other humiliating abuses that his son had purportedly experienced. The police once stripped his clothes off and hung him upside down from the detention cell’s ceiling. At another time, the investigators forcefully slapped both ears of Chuong. He also endured mental distress in police confinement as he was denied basic rights, including the right to visits by his family and legal representative.

Nguyen Trong Doan, Chuong’s brother, said that he was also assaulted by the police officers who were investigating his brother’s alleged crime of murder. Previously, Doan tried to meet and bring forward alibi witnesses who confirmed that Chuong was not present at the crime scene at the time of the murder. In a 2019 interview with Luat Khoa, Doan said the investigators shackled and hit him many times during questioning sessions. According to Doan, the police only released him after he agreed to write and sign a written confession prepared by the investigation agency, stating that he fabricated Chuong’s alibi to help his brother evade the charges.

Police brutality

Police brutality is a global predicament, and many human rights organizations and activists have opposed torture by the police against individuals with distinct racial, religious, and political backgrounds.

But in authoritarian one-party regimes like Vietnam, where the executive branch wields significant power, calls to promote greater transparency and adopt a human rights-centered approach in criminal investigation procedures have often been brushed aside.

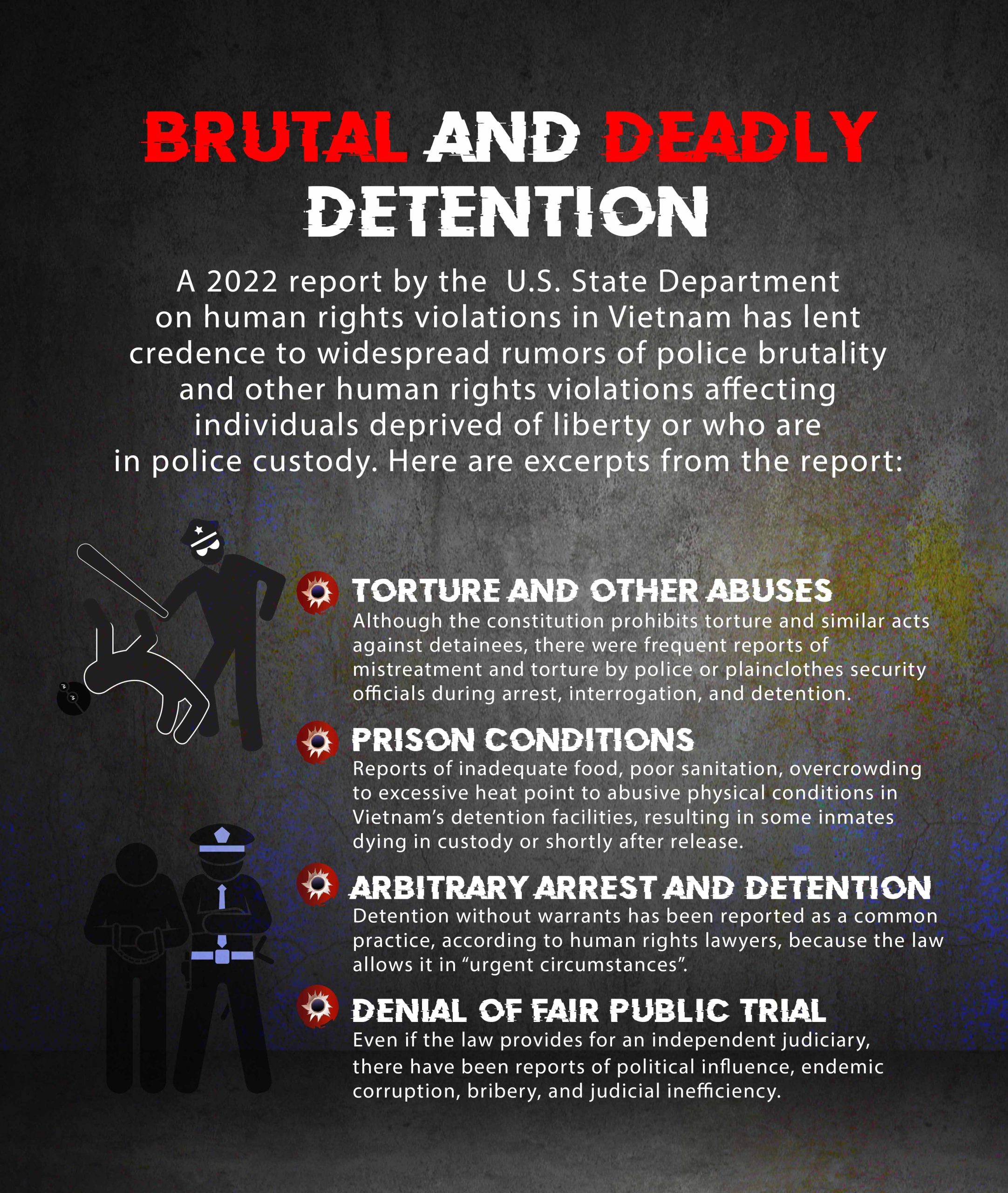

The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT), in a report released in 2016, made several proposals for Vietnam to enhance its application and implementation of torture prevention.

The UNCAT proposals specifically called on Vietnam to apply criminal procedure measures in investigating and prosecuting persons who commit acts of torture or who obtain testimonies by force; to facilitate lawyers’ engagement in criminal proceedings; study and pilot the use of audio and video recording in criminal proceedings; and strengthen education regarding the code of ethics.

It also urged the country to promote activities to improve the efficiency of law enforcement and human rights protection monitoring, and introduce anti-torture legislation mandating annual inspection and supervision of government agencies and public officials, especially investigating police forces.

In reality, little has been achieved in Vietnam since the publication of the UNCAT report. The MPS has exclusively handled the criminal investigation procedures, and nearly no efficient agencies are responsible for monitoring police criminal procedure measures or holding the officers who are suspected. of having committed torture accountable. Many reported suspicious deaths in police custody have been ignored, and no further investigation has been initiated to find the alleged perpetrators.

The incidence of suspicious police station deaths will likely remain unchanged if there are no meaningful amendments to the current criminal procedure measures of Vietnam’s law enforcement. Ultimately, only ordinary citizens suffer at the hands of merciless policemen. ◉

This article was originally published by The Vietnamese. Reprinted with permission.

Jason Nguyen focuses on vulnerable communities: ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ+ community, activists, and Vietnam War refugees, challenging the Vietnamese government’s official narratives on social and political issues.