|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The offer to fund an online activity related to digital rights in Myanmar was tempting and Nora admitted that she almost took it. But the young digital security trainer from Myanmar, where she is also based, decided to decline the financial aid from an international non-profit organization, citing both physical and digital security risks.

“The government is now watching civil society workers,” said Nora, who asked to use a nickname for safety reasons. “They track social media and also Zoom meetings of those that are working toward public awareness and also against the military.”

According to U.S.-based Freedom House’s 2022 Freedom in the World report, Myanmar has the world’s second least free cyberspace, outdoing only China. In June 2022, UN human rights experts denounced the “digital dictatorship” in Myanmar and urged the global community to safeguard the essential rights of the people of Myanmar, including freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy.

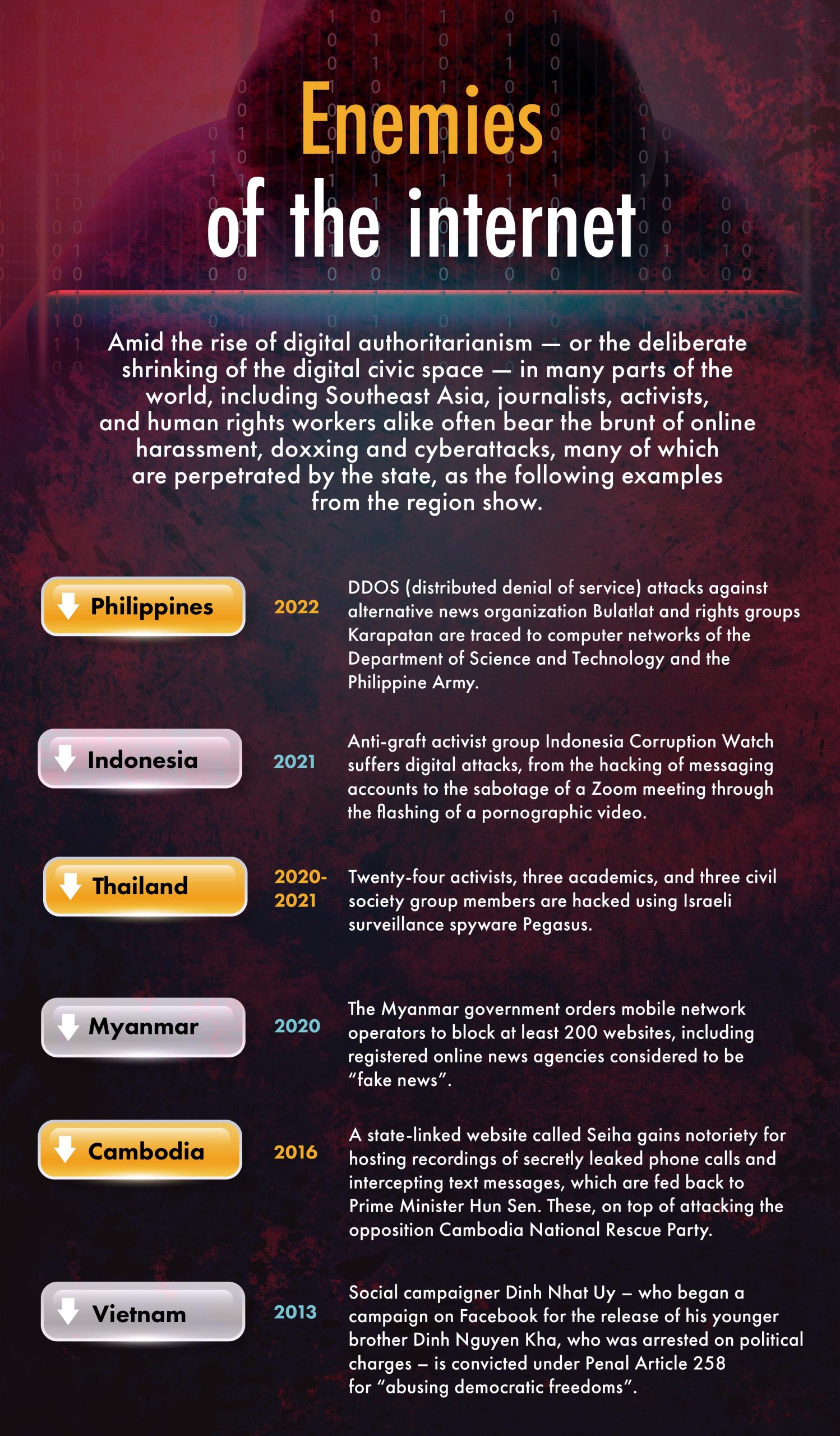

Nora said she knew specific cases in which people were punished by the government for their online advocacy. But Myanmar is not the only Southeast Asian country with worrisome internet restrictions (although admittedly Myanmar has gone from bad to worse since the 2021 military coup there). The Freedom House report indicates that with the exception of Timor Leste, cyberspace governance in the region of nearly 700 million people leaves a lot to be desired, with the internet rated as “partly free” in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Singapore, and “not free” in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, Brunei, and Thailand.

The internet has played a significant role in the democratization of Southeast Asia, which is now home to the most dynamic and diverse digital economies in the world — the total of which is expected to hit US$1 trillion by 2030. In the past several years, however, human rights challenges, which have always been a sore spot in the region, have crept into cyberspace.

Interviews conducted recently by Asia Democracy Chronicles with 14 self-identified digital-rights workers from 10 countries across Southeast Asia — Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor Leste, and Vietnam — confirm this. Indeed, it has come to a point where, one Lao journalist said, “We are not able to talk about human rights issues. We can only mention social issues.”

Digital-rights workers include cybersecurity experts, internet researchers, online journalists, and activists working on digital platforms on human-rights issues.

Online gagging increasing

The 2023 report “Human rights impacts of new technologies on civic space in South-East Asia” by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) observed, “In Southeast Asia, as elsewhere in the world, the rapid expansion of digitally enabled communications has brought about a number of new challenges: The spread of incitement, organized online campaigns targeting civil society actors and the rapid expansion of surveillance have increased the challenges faced by those engaging in public debates.”

These challenges, said the report, are: (1) dissemination of hateful, misogynistic, and discriminatory content; (2) online attacks and harassment against human-rights defenders, which result from the government’s action and (in)action; (3) surveillance technology; (4) restrictive and repressive laws and policies in contravention of international human rights commitments; (5) criminalization and persecution of online expression; and (6) top-down internet shutdowns and network interferences.

These trends, however, are not surprising in a region that has become more autocratic in the past decade. While Southeast Asia was a model for democratization for developing countries in the 1990s and 2000s, democracy has been backsliding since, a development exacerbated by the pandemic.

With the exception of Timor Leste, which is still considered a full democracy, the rest of the region have seen their civil liberties go downhill both online and offline. Voice of Democracy (VOD), one of Cambodia’s last independent media outlets, was forced to shut down last February for “hurting the dignity and reputation of the Cambodian government.” In Vietnam, where the Communist Party monopolizes the mediascape, the popular state-affiliated online outlet Zingnews had its publication suspended for three months and meted a fine of about USD $10,000 for allegedly going beyond what it had registered to cover.

Surveillance of perceived enemies of the state is now a given in many countries across the region. Comparitech, a U.K.-based company that seeks to promote cybersecurity and privacy across the globe, said that based on numbers of cameras per square mile, Southeast Asia was now home to the most surveilled cities in the world. In Vietnam, one activist said it would “not be long before facial recognition is deployed everywhere.” Several Southeast Asian governments have also purchased surveillance technology from the West, including Pegasus and Cellebrite, two popular spyware brands from Israel.

For all that, surveillance by some governments can also be old-school. Nora from Myanmar, for example, said the junta maintained lists of those who attended foreign-funded events; for Zoom meetings of its targets, it sent youths who pretend to be ordinary participants and then secretly record the proceedings.

Not content with these, all Southeast Asian nations save for Timor Leste now have laws that aim to restrict online expression, but with poorly articulated provisions that are prone to misinterpretation.

Singapore, Vietnam, and Laos, for instance, all have laws on fake news. Yet what constitutes disinformation or hate speech according to these laws is at the executive’s discretion alone. In its 2023 report, the OHCHR cited Singapore’s Protection on Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), noting that the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression had expressed concern that it could “’lead to the criminalization and suppression of a wide range of expressive conduct, including criticism of the government, and the expression of unpopular, controversial or minority opinions’ and disproportionately affect HRDs and journalists.”

In the case of Laos, the report pointed out that some UN Special Rapporteurs had also raised concerns over “the arrests of HRDs in connection with posts on Facebook criticizing the Government of Lao PDR,” as well as over “vaguely defined offenses of defamation, libel and insult, and the criminalization of the online criticism of the Government or of circulating false or misleading information online.”

As for single-party Vietnam, the U.N. Human Rights Committee also expressed concern over the Law of Cybersecurity of 2018, “which prohibits the use of internet services to criticize the State,” says the report. The Committee also highlighted the “arbitrary arrest, detention, unfair trials and criminal convictions” of HRDs, journalists, bloggers, and lawyers for criticizing State authority.”

A tech giant bows down?

U.S.-based lawyer Quynh-Vi Tran, editor in chief of the online publication The Vietnamese, meanwhile told ADC that the compliance of Meta, Facebook’s parent company, with the demands of the Vietnamese government has aggravated the dismal rights situation in the Southeast Asian country.

Facebook has about 67 million users in Vietnam as of 2023, or two-thirds of the country’s population. Tran said that in addition to agreeing to remove content deemed “illegal” by the government within 24 hours upon receiving a request from the authorities, Meta has implemented an internal roster of Vietnamese Communist Party officials who are not to be criticized on Facebook. (Meta’s Vietnam Public Policy team has yet to reply to requests for comments.)

As it is, Vietnamese authorities already block websites that they deem too critical of the government. In 2017, the Legal Initiatives of Vietnam’s two online magazines, The Vietnamese and Luật Khoa, suffered such a fate. That was also the year Vietnam’s draft cybersecurity law was circulated. It was enacted in 2018 and came into effect in 2019.

Tran said the top-down blocking of The Vietnamese’s own website made it very hard for her team to reach readers inside Vietnam. So far, she said, they have tried sending news via email and publishing multimedia content via different social media platforms. Said Tran rather wistfully: “There is no way we can go back to the pre-2017 period, even when now more and more people can use the VPN.”

A VPN or virtual private network encrypts internet connections, effectively concealing one’s location and preventing unauthorized access to one’s online activities. It thus protects internet users’ anonymity and privacy. But VPNs usually comes with a fee — and is still dependent on internet service, which can be intermittent if not cut deliberately for certain periods in many countries across Southeast Asia.

Yet many rights advocates and online journalists in the region persevere, even if several of them admit that doing so is becoming harder and harder in this era of state-subsidized troll armies. Female and LGBTQI+ activists have been found to be particularly vulnerable to online hate speech attacks, and not only in Southeast Asia. According to the 2020 UNESCO report, “Online violence against women journalists: a global snapshot of incidence and impacts,” 73 percent of female journalists worldwide experienced gender-based violence in cyberspace.

“Whenever I post my articles on my own Facebook channels, my comments are flooded with misogynistic remarks that have nothing to do with my work,” said a female online journalist based in Phnom Penh. She also said that while she received sexist remarks “on a regular basis,” these did not appear random or spontaneous. Indicating that they are the work of troll armies, the journalist described the comments as quite organized and oftentimes from clone accounts that contained little information about the commentators.

One challenge confronting digital rights workers and activists is how to continue with their advocacy without getting caught in the crosshairs of authorities. In Laos, rights activists do not even want to be referred to as such, especially after the shooting earlier this year of Anousa “Jack” Luangsouphom, a 25-year-old social media activist and rights defender who ran two Facebook pages in which he often criticized the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP).

“Digital security, integrated with a holistic security approach, stands as a key strategy to mitigate the threats we encounter and safeguard our communities as we continue our work on human rights and democratization,” said Darika Bamrungchok, program director at the activist-run Security Matters. But she said that few individuals or organizations were equipped with the necessary skills to support and strategize with local civil society communities to mitigate increasingly complicated risks confronting digital rights workers.

Computer Professionals’ Union in the Philippines chairperson Kim Cantillas, for her part, advocated for comprehensive digital literacy education that would include digital rights and security. “Otherwise,” Cantillas said, “they would simply expose beneficiaries to risk.”◉

Nguyện Công Bằng is an independent journalist who writes about Southeast Asia.

This article was developed under a grant from the Southeast Asia Digital Rights Collaborative program of the Association for Progressive Communications.