|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

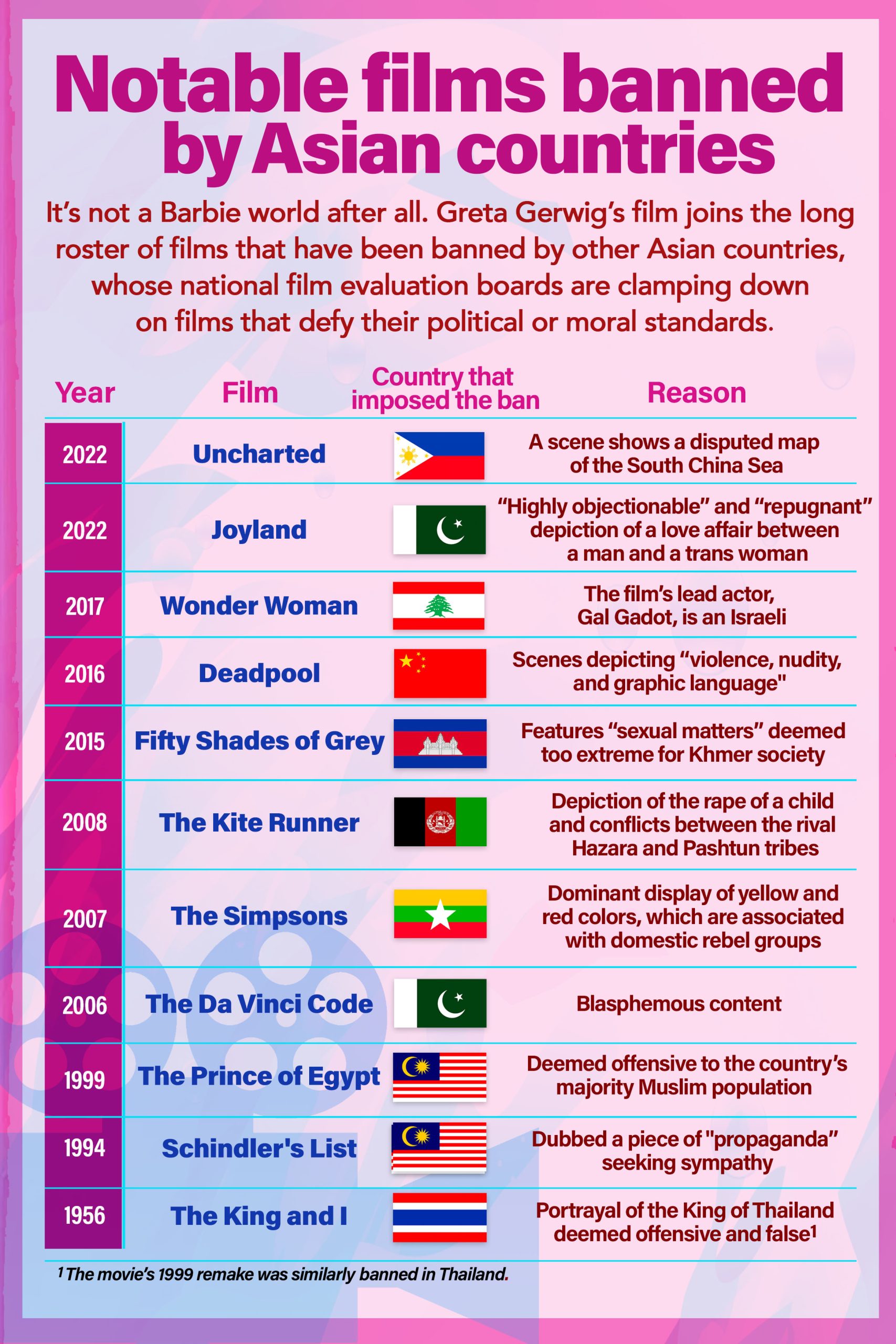

his is not the first time Vietnamese authorities have decided to ban movies over the appearance of the nine-dash line that China uses to support its maritime claims over the South China Sea. However, the decision to ban “Barbie” has been criticized more than previous bans, as the map the authorities are referring to is unclear. For example, many news outlets and netizens have questioned whether the child-like fictional map in “Barbie” actually shows the nine-dash line.

Vietnam expert Carlyle Thayer questioned the move, arguing that it did not contribute anything to the country’s national security as “it distracts the public from China’s aggressive behavior that has been taking place.”

Overreach and paranoia

While the decision seems to be a mere example of overreach and paranoia of the Vietnamese state’s propaganda machine, it supports the unrelenting efforts of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) to be seen as the defender of Vietnam’s national interests. While it may seem like an irrational decision, the controversial propaganda machine helps the VCP gain nationalist points without confronting China in any official capacity.

According to international relations scholar Le Hong Hiep, the VCP regime relies on two main sources of legitimacy to justify its monopoly of power. Performance-based legitimacy is a major tactic used by many modern authoritarian regimes, including Vietnam. According to this theory, a government (even an authoritarian one) remains legitimate if it successfully delivers socioeconomic growth.

At the same time, however, the VCP still undeniably wants to maintain its nationalist credentials. The overarching narrative that the Party pushes has always been the “inevitability” of Communist rule of the nation, and the VCP as the only rightful heir in terms of rulership of the nation.

However, this narrative is complicated by the party’s ideological alignment with China amid territorial disputes in the South China Sea, spurring many nationalist protests in Vietnam. These protests had, in the past, snowballed into pro-democracy protests.

Hence, anti-China nationalism is a double-edged sword. The VCP faces the dilemma of tolerating anti-China demonstrations, for it does not want to be seen as being soft on foreign aggression. At the same time, it also does not want to jeopardize its ideological and economic relationship with China.

As a result, in making their controversial censorship decisions on major Hollywood films, the VCP can gain nationalist credit without actually confronting China. There is a significant financial cost to these decisions as box offices in Vietnam lose out on many profitable movies, while the party uses these decisions to present an image of being tough on China without really irritating its superpower neighbor.

Hence, as irrational as it looks, banning movies like “Barbie” serves a dual purpose: it gains nationalist credit without confronting China and prevents anti-China nationalism within the country from turning into protests.

Buying the narrative?

We do not know the extent to which the public in Vietnam actually sees the VCP as the country’s protector against Chinese aggression. The saying “Trường Sa (Paracel), Hoàng Sa (Spratly) belong to Vietnam” has become a catchphrase among young Vietnamese who want to showcase their nationalism. In addition, the online presence of party defenders, such as the Facebook page Tifosi, has gathered the attention of many young Vietnamese.

There have not been any significant anti-China demonstrations for many years, but this could be explained by the people’s general satisfaction with the VCP or the party’s intolerance toward protests. In the current political climate in Vietnam, it is extremely difficult to actually find out the extent of citizen trust in the system.

However, we can look at China itself in relation to some hypotheses. Interestingly, China also has a similarly complicated relationship with anti-foreign nationalism. In his book The Party and the People: Chinese Politics in the 21st Century, political political scientist Bruce J. Dickson made the observation that China also carefully treads the line between promoting and constraining nationalism.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) wanted to promote the narrative that patriotism equaled supporting the party. It does so by trying to convince its citizens that foreign powers had oppressed China in the past and the CCP was and remains the liberator of China.

The CCP, like its counterpart in Vietnam, relies heavily on nationalism as a source of legitimacy. Yet, anti-foreign nationalism triggered unrest in mainland China in the past. For example, the anti-Japanese protests in 2012 snowballed into anti-government protests.

Dickson observed that many young Chinese made up the mass of an “angry youth” that repeatedly attacked Japan and the United States for humiliating China, making it seem that Chinese youth are becoming more nationalistic. In contrast, through a series of public opinion polls, Dickson argues that young Chinese are actually becoming less nationalistic compared to their elders.

That many observers of Chinese politics think that Chinese youth are nationalistic has to do with the loud voices of radical students on social media. These young people, often college-aged students or urban internet users, are extremely loud on social media, skewing observers’ perception of the overall sentiment of young people while disregarding the others who might not be as active on social media platforms.

While it is unclear whether this pattern in China also applies to young people in Vietnam, it is well worth asking whether the Vietnamese people actually buy the VCP’s narratives because, notwithstanding their strong online voices, the party defenders, such as those on the Facebook page Tifosi, are simply not representative of the population.

One thing is certain, though: anti-China nationalism is a very powerful phenomenon in Vietnam. Owing to its fear of anti-China demonstrations, the VCP will continue to make seemingly irrational moves, like banning the movie “Barbie,” not only to earn nationalist credit but also to appease potential protesters.◉

This article was originally published by The Vietnamese. Reprinted with permission.