|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Geopolitical tensions continue to rise in the Asia Pacific, and China is at front and center of it all. And with Beijing increasingly belligerent, China watchers are closely following its moves, including its efforts to put pressure on Asia-Pacific countries.

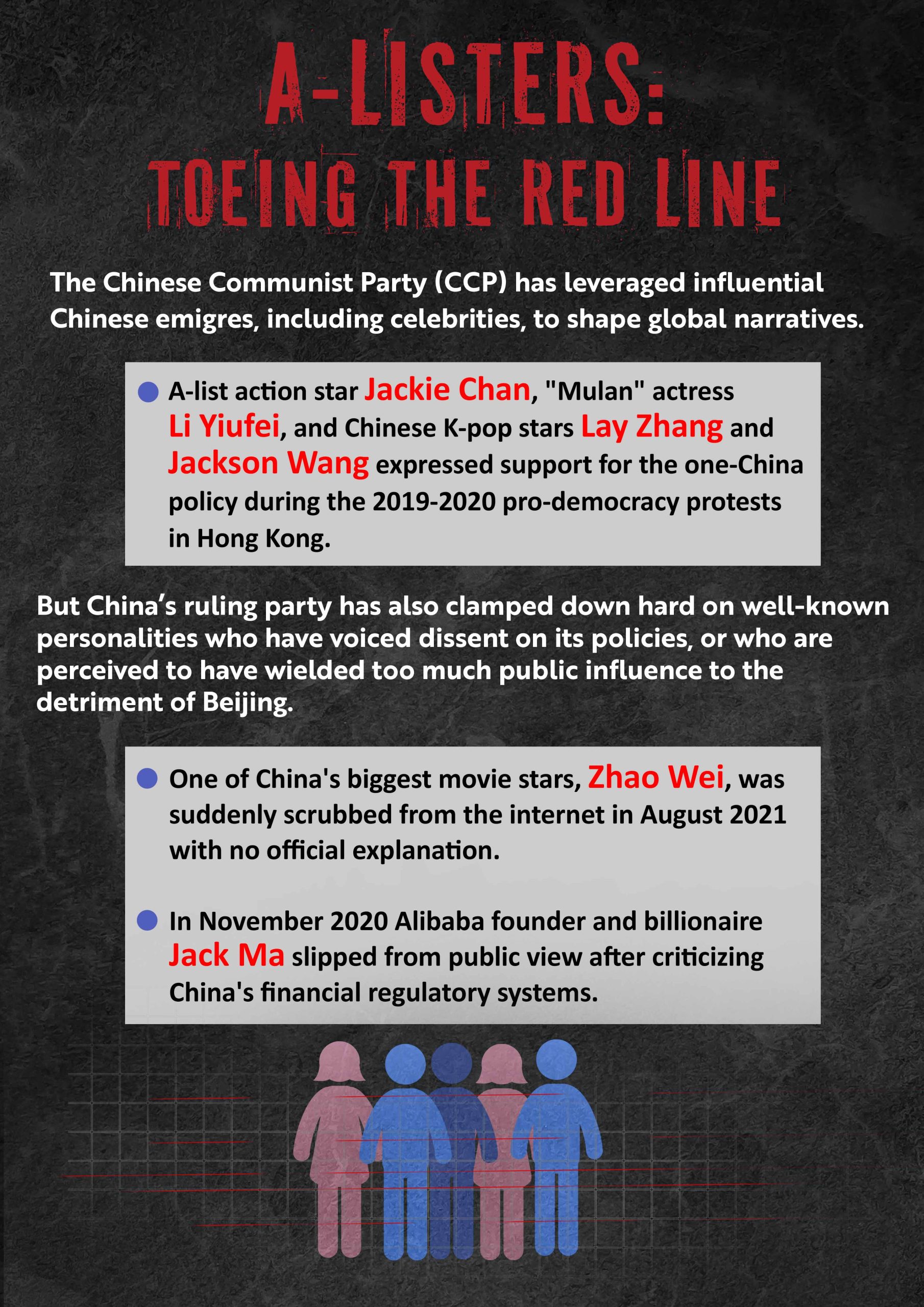

Indeed, Beijing has been doing this not only by using economic, political, and military tactics, but also through the Chinese diaspora communities across the region. As things stand, the Chinese government’s propagation of disinformation and its own political narratives in Western countries are already extensive, with Chinese state-run media such as the Xinhua News, China Daily, and CGTN now operating English-language media arms.

What has been distinctly different in the Chinese approach in the last several years, however, is that while Beijing-instigated disinformation had historically sought to promote positive views of China abroad, now it is trying to sow doubt about Western democracies. Moreover, Beijing seems to be counting on the Chinese diaspora to spread its views.

Just how big a population the Chinese diaspora has worldwide is hard to measure, since this is influenced by self-identification, and even some ethnic Chinese may not identify themselves as still part of the diaspora as generations of them have been living abroad.

Meanwhile, the Chinese state does not help to paint a nuanced picture of overseas Chinese at all. Rather, it likes to frame overseas Chinese as having a patriotic duty to the motherland, and attempting to expand influence among them by propagating this narrative. This is even though, as Dr. Khoo Ying Hooi, head of the Department of International and Strategic Studies at the Universiti Malaya, points out, “many Chinese communities might no longer feel the association with China and are assimilated somehow in the countries where they reside.”

Based on news reports and studies by academics and NGOs in recent years, Beijing has been ramping up its activities in relation to Chinese diaspora communities. But Ai-men Lau, research analyst at the Taiwan-based Doublethink Lab, says, “It is well documented that there have been substantial efforts to influence the overseas Chinese communities. However, it is crucial to remember that just because influence operations are occurring, it does not mean they are effective or impactful on the community.”

Lau was Team Leader of Doublethink Lab’s recently released pilot study, “Unpacking the Power of Propaganda: The Factors in Shaping Overseas Chinese Communities’ Attitudes Toward Pro-CCP Narratives.” Its aim was “to provide a comparative context to allow readers to … map out an overview of the factors relating to propaganda inclinations, and to provide insight as to how different local contexts can mediate local responses to propaganda.”

To have better basis of comparison, non-ethnic Chinese were also among the respondents along with ethnic Chinese, who were further subdivided into ‘Chinese (mainlanders),’ Hong Kongers, Taiwanese, and so on, based on how they identified or saw themselves.

The importance of belonging

In general, the survey results turned out to be a mixed bag; according to the Doublethink researchers themselves, the results were “surprising” and “failed to prove some of our hypotheses for this project.” Their choice of New Zealand and Malaysia as the two sources for their survey’s respondents, however, may have helped lead to one of the study’s clearer findings: among those more likely to agree with narratives that are pro-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are people – and not necessarily ethnic Chinese – who had no sense of belonging or lacked identification with their current country of residence.

The governments of both Malaysia and New Zealand counterbalance between Western powers and China while officially maintaining overtures of friendship to both. Both countries also follow the ‘one China’ policy, which means they do not have official diplomatic relations with Taiwan. New Zealand is closer to Western countries, though, while Malaysia has friendlier relations with China.

Political scientist Dr. Francis Loh says that in Malaysia, views regarding the United States have been shifting through the years. “The (Malaysian) public generally had a positive attitude toward the U.S. and a negative one toward China” during the Cold War, he says. But then U.S. intervention in other countries had been a major factor in Malaysians, particularly the Muslims, seeing the United States more negatively as years passed. This became especially so during the Trump presidency, which “revealed how ridiculous American society can be,” he adds.

Individuals of Chinese descent are close to a quarter of Malaysia’s 34 million people and make up the country’s second largest ethnic group; in New Zealand, they total around four percent of the country’s population of 5.1 million. Most of the ethnic Chinese families in Malaysia have been there for generations while the bulk of those in New Zealand are relatively new migrants, having arrived in that country after it relaxed its once pro-European immigrant rules in the late 1980s.

Today ethnic Chinese are the largest non-European and non-Polynesian group in New Zealand. But New Zealand society remains Eurocentric, while racism, subtle and otherwise, toward non-whites persists. In Malaysia, ethnic Chinese have made major inroads in the country’s commerce, but still have to contend with government policies that are skewed to favor ethnic Malays.

It would not be surprising then if the ethnic Chinese and other minorities in these countries felt less than welcome despite being longtime residents there. Notably, too, Beijing’s increased efforts to expand its influence globally have been taking place at a time of heightened backlash against members of the Chinese diaspora.

Given the Chinese origins of the coronavirus that spread worldwide beginning in 2020, individuals of Chinese descent outside of China have experienced even more discrimination and violent attacks than usual, probably weakening their sense of belonging all the more, which in turn makes them more susceptible to the claims of a nation that is all too happy to say they are part of it.

That the respondents who identified as Chinese were more inclined to agree with Chinese propaganda may practically be a given. But respondents with mixed identities or who viewed themselves as Chinese Malaysians or Chinese New Zealanders, rather than seeing their Chinese identity as taking precedence, were also more likely to take stances in line with the Chinese government. They therefore were more prone to accept that the Uyghurs in camps in Xinjiang were not being detained but instead were receiving vocational training, and that COVID-19 originated in the United States rather than China. Generally, though, there was still less belief in Chinese propaganda about Uyghurs compared to other issues.

Such individuals were also found to be more prone to accepting an overall worldview more skeptical of domestic governments and having less faith in domestic government institutions. This dovetailed with agreement with the viewpoints of countries geopolitically aligned with China – such as those of Russia, among which is the notion that Ukraine provoked the invasion through becoming too close with NATO.

Put another way, the Doublethink study suggests that the propaganda narratives increasingly lead to domestic polarization in which agreement with Chinese propaganda correlates to belief in Russian propaganda. But, as this correlates with disapproval of domestic governments, this could potentially be leveraged by Beijing to expand China’s influence among diaspora populations and beyond.

Multi-pronged campaign

As it is, Beijing’s efforts to influence local politics can already be extensive. A report released this year by Alliance Canada Hong Kong, a campaign led by pro-democracy Hongkongers in Canada, found that Chinese attempts to influence Canadian politics, alongside efforts to spy on or threaten dissidents, have been wide-ranging. Yet those outside of diaspora communities often did not recognize such influence. The report also mentioned in particular the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) United Front Work Department (UFWD), which it said uses proxy actors as it goes about garnering “public support for the CCP, including silencing dissidence, swaying public opinion, and establishing networks of influencers.”

Just last year, the pan-Asian rights group Safeguard Defenders released a report that revealed China had been operating at least 102 police stations outside of its borders. These overseas police stations – usually masquerading as local community organizations or Chinese hometown associations – are apparently being used to threaten, harass, and monitor members of the Chinese diaspora, especially dissidents living abroad, or otherwise seeking to keep such communities in line. The same outposts are also being used for mobilizing around specific political events, with the aim of pressuring local politicians.

China is thus using a multi-pronged approach to spread – and even force on others – its narratives. Propaganda may be one of its more benign methods, but that doesn’t make it less effective or less dangerous.

Yet part of the danger is that overseas Chinese are viewed in homogeneous terms by western policymakers, who may not understand the complicated nuances of identity among diaspora groups.

Observes Lau: “The overseas Chinese community is caught between a rock and a hard place. The Chinese Communist Party has intertwined ethnicity and culture to loyalty to the party and does not view overseas ethnic Chinese communities as separate from the state. Whereas the West does not have a nuanced understanding of the community either and has the danger of slipping into racist tropes and stereotypes of the community.”◉