|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

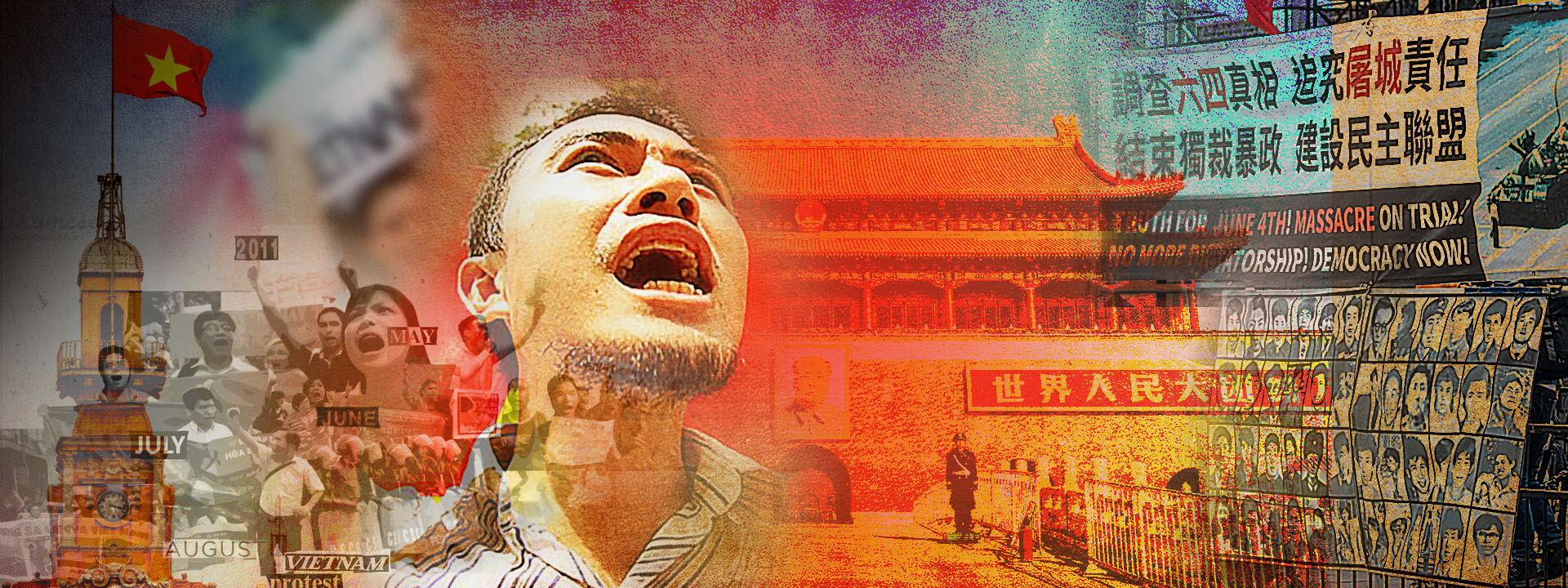

My colleague Trinh Huu Long’s story of how he became a human rights activist has been a source of inspiration for me. That turning point in his life all began on June 5, 2011 when he decided to join a protest against China’s aggression on the East Sea (or the South China Sea as China calls it) in Hanoi.

Joining a demonstration in Vietnam in 2011 was courageous because Vietnam never passed laws guaranteeing the right to form an assembly and join a protest. These laws were so vague and arbitrary that many foreigners mistook them to mean that protests and public demonstrations were outlawed.

The night before June 4, 2011 Long asked himself what the Tiananmen students would do if they were in his situation? Would they join a protest, or simply stay home in fear of being arrested? Long concluded that the Tiananmen students would go to the protest, and so he did.

As a result, Long was arrested and detained for three days. This marked a turning point in his life as he decided to become a human rights defender in Vietnam. When I met him nine years ago, we agreed to form our first publication as an independent newspaper focusing on Vietnam. Later I met a few Tiananmen students who dreamed of seeing China as well as Vietnam become democratic countries.

This shared dream would later inspire me to focus my thesis at Columbia University on the Tiananmen students who inspired many people from different parts of the world, including those of my own country, Vietnam, to fight for democracy and human rights. Here are excerpts.

***

I

n late November last year, a political event in China surprised many people worldwide. University students in China began public protests, starting at Tsinghua University in Beijing and spreading later to different provinces in the country. The students demanded that the Chinese Communist Party and its leader, Xi Jinping, cease their zero-COVID policies – or step down from power.

Protests broke out four days after a fire gutted a high-rise apartment in Urumqi, Xinjiang, killing ten people, including children. The local authorities could not stop the fire from spreading as China’s COVID policies prevented firefighters from coming close enough to put the fire out.

During the protests, each rallying student held up blank sheets white A4 paper. The movement was quickly dubbed the “A4 Movement” by the foreign press.

For over 30 years, the world thought that no one in China would dare do such a thing because it was dangerous, recalling the violent incident that unfolded in Tiananmen Square many years ago.

Back in the late spring and early summer of 1989, university students in China rose and protested peacefully for more than two months. The final moments of those protests occurred on June 4, 1989. Outside of China, this historic moment came to be known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, so-named because hundreds, perhaps thousands, of students were killed by military troops in the middle of that vast open plaza in the center of Beijing after a series of protests.

In China, you cannot discuss the Tiananmen Square massacre, or search for it online. In Hong Kong censorship of any reference to the June 4, 1989 violent crackdown was intensified when pro-democracy Hongkongers held their last annual commemoration of the incident three years ago with a candlelight vigil. In 2020, such an activity was banned by the government citing COVID-19 restrictions. The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China defied the rule, leading to the arrest and conviction of a dozen activists, recounted Johnson Yeoung, a young democracy advocate in Hong Kong. By 2021 the annual commemoration of the Tiananmen Massacre had become “illegal” in Hong Kong, he said.

After the Tiananmen Square Massacre in June 1989, the protesters were scattered far and wide. Many were arrested and jailed, while others fled Beijing. Some remained in China and stayed silent; others were allowed to travel abroad, and continued their activism and fight for democracy in China.

For Tim, who declined to disclose his real name, the Tiananmen protests should be called “the 1989 Democracy Movement.” By calling it the Tiananmen Massacre, he said, the foreign press had put the focus only on the night of June 3 and the early hours of June 4, 1989, when tanks rolled in and killed many of the protesters. The last episode of that event did not fully convey the importance of the larger democratic developments taking place at the time in China.

“The 1989 Democracy Movement challenged [the] legitimacy of the ruling Communist Party in China,” Tim said. “This is the reason for the Chinese government’s efforts to erase it from the country’s collective memories since [then].” In his view, the A4 Movement of 2022 brought back memories of the 1989 Democracy Movement in China.

The opportunity for democratization in China was lost in 1989 when military tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square, he said. Yet, the Tiananmen incident remains one of the most important historical events over the last century in China. The peaceful protests and lectures in the lead-up to the June 4th incident about democracy, which were conducted by students and university professors, inspired many different groups, including workers, and saw the emergence of reformists from the Chinese Communist Party.

“I believe the people have to fight for a democracy,” Fengzuo Zhou, 55, said just weeks before the A4 Movement broke out. “[They] should not wait for it to be given to them by those who are in power.”

Zhou was a student-activist at Tsinghua University in Beijing in 1989 and was number five on the most-wanted list of the government before he was forced into exile in the United States. In 2007, he established Humanitarian China in the U.S. to assist human rights activists within China.

To Tim, Zhou, and other pro-democracy Chinese activists in the U.S., China got very close to achieving “liberty” in 1989 – until violence unfolded, killing many of the protesters, alongside their hopes of achieving democracy.

All is not lost, however.

A new democracy movement

During the A4 Movement protests last fall, rallies in solidarity with the protesters in Beijing were held in other cities worldwide. Shawn S., a Chinese undergraduate at Columbia University in New York who also asked that her last name be withheld for security reasons, joined one such rally last December at New York’s Washington Square Park. Dressed like one of the students in the fictional Hogwarts School in the Harry Potter series, Shawn wore a short beige peacoat over her white, long-sleeved shirt. She said she believed that the protesting Chinese university students wanted to show the world that they had no specific demands when they held up blank A4 papers and that the documents represented them.

“We are the generation who had nothing,” Shawn said. More than that, blank A4 paper was convenient for the protesters because it was readily available, and everyone could simply grab a sheet of paper and go.

But would holding up a blank piece of paper during protests shield the Chinese students from government suppression?

Shawn covered her face with a mask and wore oversized sunglasses at Washington Square Park. The risk was much greater for the university students in China who did not cover their faces.

In January 2023, just two months after the A4 protests began, the Chinese government relaxed its zero-COVID policies and seemed poised to eliminate them completely. While it might seem that the government had conceded defeat during the A4 Movement, the loosening of COVID restrictions also forced the students, now that their demands had been met, to end their protests while many of them were arrested. Nonetheless, their protests remain a remarkable – and an inspiring – display of bravery.

The swiftness of the Chinese government’s reaction was critical. The fact that the protests started after the deadly fire in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, showed that ordinary Chinese citizens would take action when they saw the government’s wrongdoings toward other ethnic minorities – such as the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Han Chinese students in the A4 Movement rose in solidarity with the people in Urumqi because they knew that the zero-COVID policies could also affect their lives. They did not wait to act only if the government committed misdeeds against their own ethnic group. Their empathy for another ethnic minority could be an early sign of mobilization among different groups in China.

When the Chinese diaspora students learned about the protests in their country, they tried to link themselves with the movement as a demonstration of their support. Such solidarity showed that not everyone in China had been brainwashed by the state. Another positive sign among the diaspora students from China was their expression of support for other ethnic groups like the Tibetans and Uyghurs.

Seeing what happened at the fire in Urumqi, the Han Chinese also realized that their government could treat them as harshly as it did the people in Xinjiang. This understanding strengthened the solidarity among different ethnic groups in China.

That is a good thing for China, or, better still, its citizens who refuse to forget the hopes and dreams of the brave men and women who fought at Tiananmen Square. ◉

This article is a condensed version of a master thesis submitted by Vi Tran, editor-in-chief of The Vietnamese Magazine, to Columbia University in April 2023. Republished with permission.