|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A

gambit, under any circumstance, is a problematic move. Between nations, players locked in a gambit would have to know what exactly, and what separately, they are giving and getting.

By all accounts, the gambit now playing between China and the governments of Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Fiji has become a cost-benefit equation.

Nearly all the benefits go to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), China’s state-owned enterprises and business entities, and their political allies and partner corporations in the four countries.

In contrast, nearly all the cost is borne by the people, the economy, democratic institutions, and the rights and welfare of workers and citizens, in the same four countries.

To claim and assert its role as a global superpower, China plays this gambit. And where it does, the most tragic cost has been a palpable decline in the scope and state of democracy, human rights, and transparency and accountability of its national government allies.

China has tossed tons of aid, loans, grants, project funds for any and all imaginable purposes and sectors; unveiled aggressive exchange programs and content-sharing agreements with academe, media, and Chinese diaspora entities; poured funds and supplies for “vaccine diplomacy” during the COVID-19 pandemic; and pushed trade, training, and contracts with Chinese corporates in security, defense, telecommunications, and information and communication technology – in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Fiji – where democracy remains fragile, state agencies are weak and compromised, and economies in dire need of funds to expand and grow.

The results are invariably so corrosive to democracy, accentuated by corruption, patronage, repression of freedoms, among others.

In hot pursuit of dynamic economies

Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Fiji are among Asia-Pacific’s most dynamic economies, and hold significant geopolitical sway in the region.

Indonesia and Thailand (with Malaysia and Singapore) control the Malacca Strait, where up to two-thirds of China’s maritime trade volume and around 60 percent of its entire oil supply pass through.

The Philippines controls parts of the South China Sea where around US$1.5 trillion worth of Chinese trade happens, as well as several chokepoints such as the Bashi Channel, which serves as an access to the Pacific.

Fiji, on the other hand, serves as a regional diplomatic hub in the Pacific, which the Chinese government has eyed constantly amid the decision of several Pacific Island nations to recognize Taiwan.

The Belt and Road Initiative or BRI, together with loans, development aid, and other economic and diplomatic measures, have become China’s tools to incentivize, coerce, and co-opt actors in these countries.

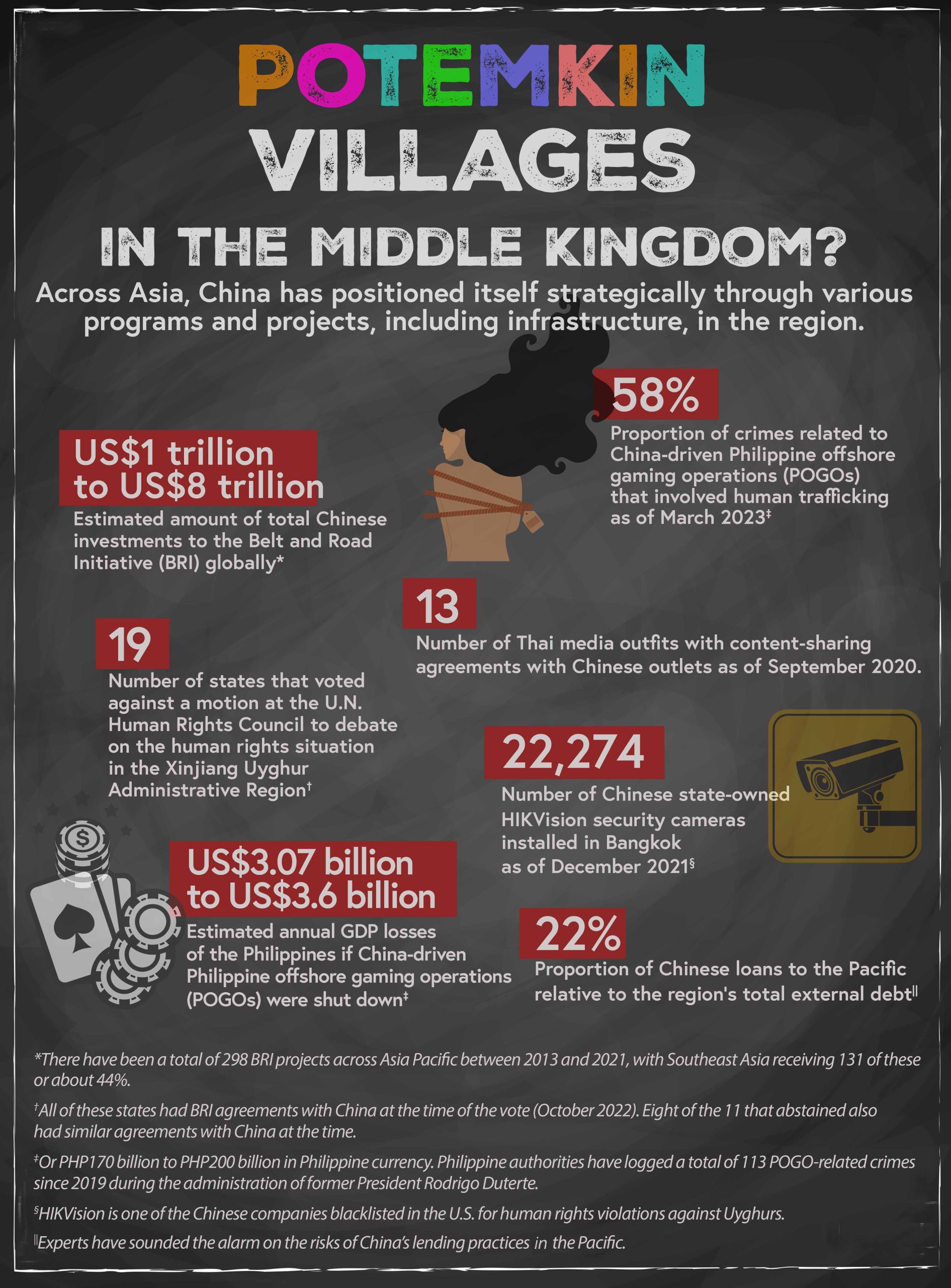

Estimated to have US$1 trillion to US$8 trillion worth of investments, BRI alone is seen by many countries as an attractive source of developmental resources. The four countries have been eager to access BRI resources to augment and complement their own domestic development plans – Global Maritime Fulcrum in Indonesia launched in 2014; Build, Build, Build in the Philippines launched in 2017; Thailand 4.0 launched in 2016 and its centerpiece Eastern Economic Corridor program; and Transforming Fiji 5-Year and 20-Year National Development Plan launched in 2017.

When these developmental plans were launched, the governments of the same four countries were facing heavy scrutiny of their democratic records.

Indonesia’s Joko Widodo was turning more anti-secular and nationalistic; the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte was on a murder spree with his “War on Drugs”; Thailand’s Prayuth Chan-o-Cha was filing strategic litigation against public participation cases (SLAPPs) against critics years after the 2014 military coup that he led; and Fiji’s Frank Bainimarama was comfortably continuing his authoritarian ways following the 2006 military takeover that had him at the helm.

Years of illiberal rule in the case of Fiji and Thailand, or the stagnation of democracy in Indonesia and the Philippines, left regulatory agencies compromised, inefficient, and failing.

To be sure, China’s actors get what they want, and their domestic partners get what they need. Little or no transparency marks the conduct of these deals, however. And when China-funded projects run into delay, controversy, corruption, or altogether fail, not much outcry has been heard from national agencies and the controlled or captured media in China and the four countries.

Worse, the adverse impact of Chinese projects on the environment, the harassment and violation of workers’ rights, and bad business practices by Chinese corporations have fallen on deaf ears.

Human rights in the back seat

Freedom, human rights, and the people’s economic well-being and welfare have often played second fiddle in the altar of Indonesia’s state philosophy of Pancasila. Authored by the nation’s founding leader Soekarno in 1945 at the preparatory committee for Indonesia’s independence, Pancasila stands for the Five Principles of “Indonesian nationalism, internationalism or humanism, consent or democracy, social prosperity, and belief in one God.”

In the last half-century, however, Pancasila has rendered Indonesia vulnerable to illiberal actors, notably China, which has vigorously sought to fashion and impose its own notions of democracy outside its borders.

Under President Joko Widodo’s watch, China’s BRIs and bilateral agreements with Indonesia have triggered profound negative economic and fiscal impacts rather than the claimed positive results. Investment ventures backed by the Chinese government have been accorded National Strategic Project status, despite adverse results on the socio-economic conditions of their host communities, environmental damage, and restraints on the rights of workers and press freedom.

According to AidData, a research and innovation lab in the United States, between 2009 and 2019, Indonesia received a total of 264 various loans, grants, “buyers’ credit,” and technical assistance that were worth innumerable billions of dollars from the Chinese central government, state agencies, and state-owned companies and conglomerates, along with the Export-Import Bank of China, Bank of China, and China Development Bank.

In the Philippines under former president Rodrigo Duterte, Manila’s foreign policy marked a pivot from decades-long dependence on the United States to tight bonding with China. Cases of extrajudicial killings drew no criticism or rebuke from China. Instead, China gave grants to build drug rehabilitation facilities for Duterte’s bloody ‘war on drugs,’ and promised multi-billion dollars of loans to build bridges across the nation.

Until Duterte’s term ended on 30 June 2022, most of the pledges remained pledges, and multiple ‘flagship projects’ that China was supposed to bankroll remained plans, while the few that pushed through still face resistance by affected communities.

Instead of genuine development projects funded with China money, what actually became real under Duterte was the bolder claim and bigger presence of Chinese naval militia, weaponry, and troops in the West Philippine Sea.

The conflict has hit home among Filipino fisherfolk, who together with farmers make up the poorest sector of Philippine society.

China’s BRI became one of the focal points of the Duterte government’s cordial relations with China, despite ongoing territorial issues, low public opinion of China, and the Philippines’ security partnerships with major powers defending the current international order.

The signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on BRI Cooperation during Xi Jinping’s November 2018 visit formalized the era of greater cooperation between the two countries.

Many scholars and analysts have raised numerous concerns about the BRI projects including BRI as the source of a new debt trap, particularly after revelations that Sri Lanka was forced to cede control of its Hambantota port to China for 99 years, following the island nation’s failure to repay its debt.

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, Thailand has tried to maintain a foreign policy that would enable it to be open to relations with both China and the West. However, the latest power grab (2014) by the military has pushed it closer to Beijing.

In recent years, Thailand has secured record values of Chinese investments, aid, loans, and bilateral agreements from China, across major sectors of the economy, defense and security, state and private media, and education.

Of at least 12 military-led coups that have been successfully staged in Thailand since 1932, General Prayuth Chan-o-Cha’s 2014 coup came at a transitional period, and after the death of King Bhumibol. Prayuth set up military officers as Cabinet members and ushered in more favors for Thai conglomerates; with it have been more human-rights violations, and the arrest of civil-society leaders and critics. Statements of condemnation were released by the United States, the European Union, and some members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). China, in contrast, voiced support for the putschists.

Thailand’s military government expressed appreciation for China’s understanding, launched its ‘Thailand 4.0’ economic policy, which emphasizes research and development, and leaned more and more toward Beijing for aid, trade, and support.

Chinese direct investment to Thailand has progressively grown from 2015, when it ranked fifth place among foreign direct investment (FDI) sources. In 2019, China soared to first place as Thailand’s FDI source, surpassing Japan for the first time. China slipped to second place after Japan in 2020, but over the next five to 10 years, Bangkok is projecting that China will once again be No. 1, according to a Bangkok Post interview with the Board of Investment deputy secretary general.

Strategic inroads into the Pacific

China has had a wide range of strategic political, economic, cultural and diplomatic interests in the Pacific, with Fiji playing the role of a pivotal partner, given its status as the hub of the Pacific, and the base for most of the multilateral and regional organizations.

China is now the second largest donor in the Pacific, and the largest bilateral donor of Fiji.

Chinese aid to Fiji in the seven years to 2013 actually exceeded its traditional aid donor, Australia’s contribution by more than US$110 million. A good number of Chinese firms and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) now have large-scale operations in Fiji, concentrated in construction, mining, logging, and fishing.

Economist Pryke opined that in the last two decades, China’s Pacific expansion has occurred at a much faster rate than what could be considered a natural reflection of China’s growing economic and geopolitical clout, raising major questions about China’s ambition in the South Pacific, and what risks this creates for countries in the region.

Considering their present trajectory, Fiji-Chinese ties and contacts look set to increase. But while the Fiji government is adamant about the benefits of the partnership, there are persistent concerns about the influence and impact of the world’s most populous country – and second largest economy – on a small Pacific Island country. The more China becomes embedded in Fijian state and society, economically, politically, socially, the more the concerns, especially given the trend observed in some other countries and regions.

By multiple mode and manner, the China gambit unfolds largely unchecked in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Fiji. This has given rise to real, urgent concerns that deserve further and sustained inquiry and action by all stakeholders, and national and global democracy advocates. ◉