|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

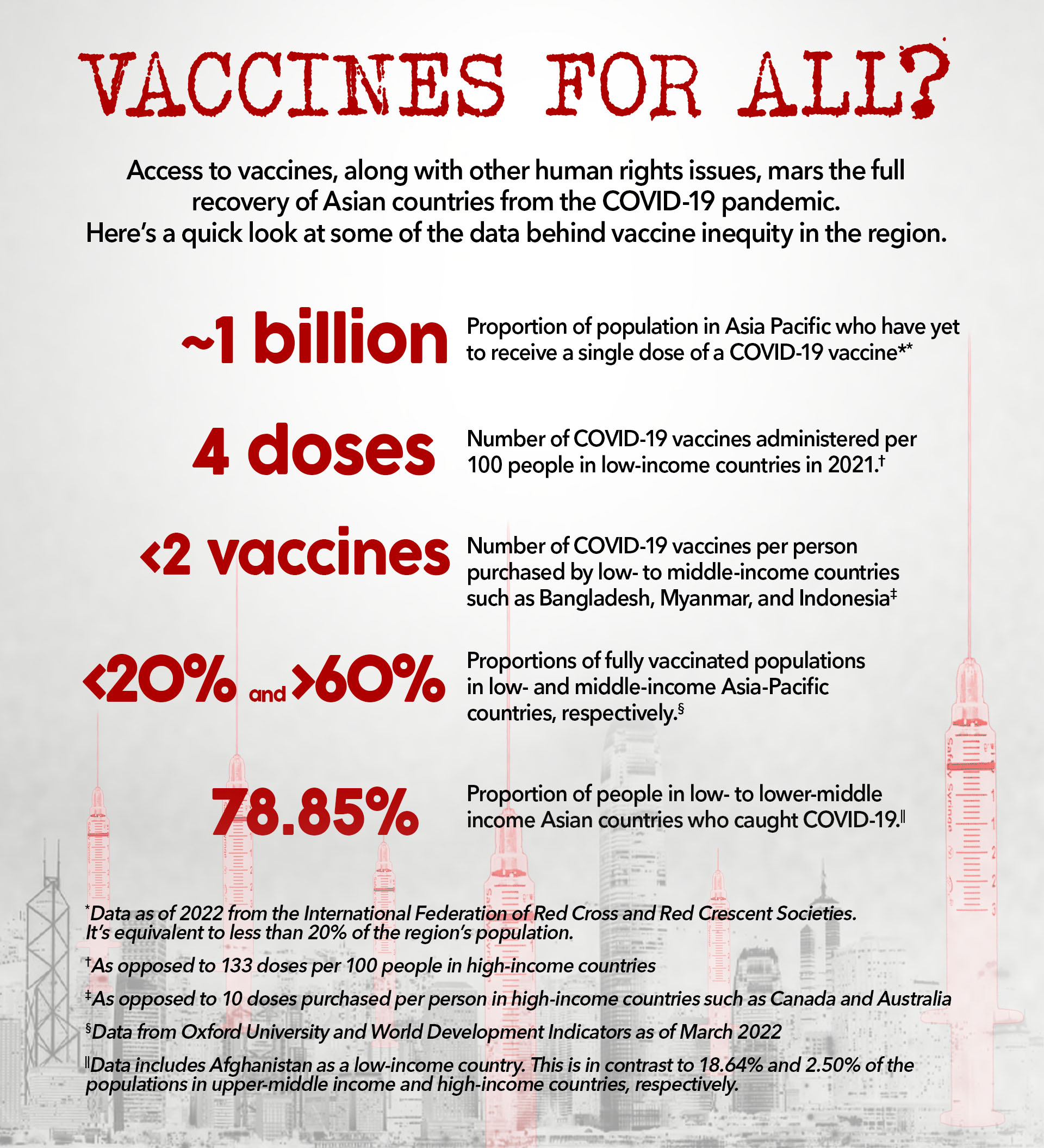

While the COVID-19 pandemic affected everybody, it laid bare country-specific socioeconomic and political challenges. Beyond existing inequalities, social stratification is magnified through differences in access to pandemic-related protection, services, and information. It created a crisis where public health infrastructure struggled with high demand for healthcare, leading to a gap in vaccine equity. The severity of this crisis is even more alarming in the most vulnerable and least developed countries.

On a global scale, there was a stark difference in access to vaccines between the Global North and Global South. With vaccines initially developed by a handful of countries, the rest of the world had to rely on existing diplomatic ties, purchasing power, and donations to access vaccines. Meanwhile, inequities between populations at the subnational level, exacerbated by socioeconomic, geographic, and citizenship status, resulted in further uneven access to COVID-19 vaccines. Different countries have implemented different strategies for distribution. Some have kept vulnerable and marginalized populations in mind, whereas others have implemented generalized distribution and inoculation strategies without considering them.

COVID-19 and human rights

There were human rights issues that went unaddressed during the pandemic. In Mongolia, the National Human Rights Commission of Mongolia (NHRCM) and civil society reported that human rights violations led to the resignation of some government officials.

Some common issues and trends emerged across the 11 countries during COVID-19:

- Governments responded with stringent lockdown, especially as subsequent variants hit. Countries, including Mongolia, Thailand, Kazakhstan, and Timor-Leste, have declared emergencies. The use of an Emergency Decree in Thailand gives a wide range of powers to the state with limited liability, which creates a decisive centralized decision-making apparatus that makes it difficult to hold the government accountable.

- Notwithstanding differences in economic status, all countries face constraints on their local capacities to recover from the pandemic.

- The pandemic has severely affected already marginalized groups that lack access to resources in most countries, including India, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Afghanistan. For example, the disabled population in Afghanistan was initially excluded from groups prioritized for vaccination.

As the world adjusts to the COVID-19 pandemic, most COVID-19 dashboards have stopped updating. This created challenges for the researchers to obtain updated data on the fully vaccinated rate for the eligible population. Not all data found by the researchers are disaggregated and updated. Hence, some countries have unconfirmed data, while others have to rely on the limited information provided by alternative sources. For instance, Kazakhstan has no particular figure for its vaccinated eligible population. Moreover, while full vaccination generally refers to two doses, in the Philippines, it also covers those who got the single-dose vaccines like Janssen (J&J) and Sputnik Light.

Vaccines: Strategic commodity or public good?

The research focus countries except India have received Chinese-made vaccines. India attempted to fill the vaccine gap with the hope of changing geopolitical tides in its favor but was unable to deliver. China met this vaccine access gap in South, Central, and Southeast Asia. This dilemma of vaccine equity reveals how geopolitical contestation has impacted international vaccine equity: vaccination has become a strategic commodity rather than a global public good, as countries that can afford to produce vaccines use vaccine diplomacy to pursue national interests and geopolitical gains.

China has emerged as the largest vaccine supplier to most countries covered by this research, including Indonesia, Bangladesh, Timor-Leste, Cambodia, and Afghanistan. Owing in part to India’s inability to provide vaccines to Bangladesh and Afghanistan as promised, China has become the largest vaccine supplier in South Asia.

China has emerged as the largest vaccine supplier to most countries covered by this research, including Indonesia, Bangladesh, Timor-Leste, Cambodia, and Afghanistan. Owing in part to India’s inability to provide vaccines to Bangladesh and Afghanistan as promised, China has become the largest vaccine supplier in South Asia.

After the U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021, leading to the return of the Taliban, China grabbed the opportunity to fill the vaccine gap. It is also noteworthy that although China has made major donations to most countries featured in this research, there have been adverse reactions to this endeavor in countries such as Cambodia, Timor-Leste, and Kazakhstan.

Information accessibility

No country has comprehensively reported good practices for obtaining information about procured or received COVID-19 vaccines.

In Timor-Leste, it remains a challenge to access updated information about the number of people who have received vaccines and the type of vaccine used. In Bangladesh, neither the Surokkha app nor the national dashboard includes vaccine price, batch number, expiration date, or waste information; this information is confidential and only accessible by filing a right to information (RTI) application under the Right to Information Act of 2009, which can take months or years to process. In Thailand, the government has never publicly disclosed vaccine delivery records, distribution data, existing vaccine stock, vaccine expiration or wastage information, or expenses incurred during vaccine procurement. Local media outlets have submitted requests but received no responses.

In Indonesia, policies targeted at the vaccine procurement process do not oblige responsible government agencies to disclose public information. For instance, the responsibility of government institutions to disclose information on vaccines is not specified.

In Mongolia, detailed information, including about vaccine procurement, distribution, availability, expiration, and wastage, was not available in government portals. In Nepal, for months, there was little information on the vaccines being provided and no breakdown of how many people had received each vaccine, along with details about the vaccines, doses of each administered, manufacturers, and expiry dates. In Cambodia, there is no detailed breakdown of procurement, donations, and related incurred costs, such as storage and maintenance. Moreover, sources of the total figures of vaccines received, doses remaining, wastage, expiry dates of vaccines, and medical waste management are not publicly available in one portal or location.

Vaccine equity

All 11 countries had priority sequences that used a phased approach in their vaccination strategies. In all of them, supply constraints informed the vaccination policy.

In Mongolia, information about such prioritization was unclear from the start; the ministerial order of vaccination listed target groups without a precise priority sequence. The vaccination drives in most countries prioritized high-risk groups, including healthcare and frontline workers.

Differing safety approaches meant that children were vaccinated in some countries and not others. In some countries, children under 12 years were also included in the vaccination groups. In India, the priority sequence is only until the age of 12. Bangladesh started its COVID-19 vaccination campaign for children ages 5–11 in August 2022. In Indonesia, vaccination targets include children ages 6–11.

Apart from local governments, private sector companies have been involved. Such practices allow for greater coverage, but they also put vaccines out of reach due to rent-seeking by private actors.

The decentralized approach raises questions about who should be responsible for ensuring the equitable distribution of vaccines.

Vaccine hesitancy has been another issue in all 11 countries. Distrust in the effectiveness of Chinese vaccines was significant in Mongolia, Cambodia, Timor-Leste, and Nepal. In Bangladesh, distrust of Chinese vaccines is also among the reasons for this, including based on misinformation. In Mongolia, due to a lack of substantial knowledge and information on various types of COVID-19 vaccines, people were hesitant to be vaccinated during the early stages of the vaccination program.

In Thailand, geographical distribution of vaccine coverage showed a clear pattern of inequality. As of December 2022, 54 of 77 provinces recorded more than 70% two- dose coverage, including 112% coverage in Bangkok (suggesting that a considerable number of non-residents travelled to Bangkok to get jabs).

There has been significant inequity in vaccine distribution across gender lines and marginalized groups — especially refugees and migrant workers. This has led to debates regarding discrimination.

Research suggests three factors have led to gender inequity in vaccination in India: a patriarchal structure that discriminates against women’s right to access healthcare services, limited digital access for women, and misinformation about how vaccines can affect menstrual and women’s sexual health. In neighboring Bangladesh, a glaring disparity could be seen as sanitation workers, garbage collectors, cleaners, and other informal workers exposed to the virus were left behind in vaccination. This has also been the case for vulnerable groups such as indigenous peoples, people who live in slums, and the transgender community in Bangladesh.

Chinese vaccine diplomacy

Chinese vaccines have become the primary avenue for some countries to increase vaccine equity. In Timor-Leste, the government formally asked the Chinese government to increase the supply of vaccines to support existing vaccine stocks. In Nepal, civil society likewise asked the Chinese government to do so. At the same time, resistance to Chinese vaccines has also been high.

Many countries have had debates about whether to use Chinese or non-Chinese vaccines, with implications for how much of their population gets vaccinated.

Agreements between China and Bangladesh on the purchase of Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines in massive quantities illustrated how one country’s dependency can be leveraged by another country for strategic or political gains. Around the same time that China sent Bangladesh 500,000 vaccine doses, it warned Bangladesh against joining the “Quad Alliance” (with Australia, India, Japan, and the US) or risking its bilateral relations with China.

Transparency and accountability

The 11 country reports show similarities in their findings on vaccine transparency and accountability. Research indicated the lack of a mechanism to verify government data and disclosures related to COVID-19 vaccines, as well as a lack of subnational data on vaccination and the pandemic situation. In Bangladesh, procurement irregularities and a lack of transparency have repeatedly been raised as causes of concern. No details regarding the procurement process for any brand were made public in Thailand, and Kazakhstan lacked clear procedures or publications on vaccine procurement or spending contracts.

In all 11 countries, research indicated the lack of a mechanism to verify government data and disclosures related to COVID-19 vaccines, as well as a lack of subnational data on vaccination and the pandemic situation.

Without sufficient checks and balances in place, all of these countries faced the possibility of corruption.

While all 11 countries have somehow managed to contain the spread of COVID-19 through their respective vaccination strategies, the pandemic has revealed the structural inefficiencies they must address in the long term to improve their preparedness for providing healthcare services and capacity to cope with further health emergencies. ◉

This article is a condensed version of Innovation for Change (I4C) – East Asia’s report, titled Vaccination Equity, Transparency and Accountability: Realities and Dilemmas.

I4C-East Asia collaborated with I4C-South Asia and I4C-Central Asia, and worked with 11 researchers from these three Asian subregions, in undertaking this co-created research project.