|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A

ruling by the Fukuoka Supreme Court last March that exonerated a 24-year-old Vietnamese woman from the crime of abandoning the bodies of her stillborn twins has become a landmark verdict for activists fighting for better conditions for migrant workers in Japan.

Workers` rights groups say the case is a major step forward in their long campaign to respect the rights of foreign labor in Japan. The case of Le Thi Thuy Linh in particular has highlighted the isolation and lack of medical care especially for female migrants who work long hours, receive low pay, and are under the rigid control of their Japanese bosses.

Rights activists, however, have been unimpressed by an announced move to abolish the scandal-ridden Technical Intern Training Program (TITP), which brings foreign workers into Japan, and replace it with a fresh, new system. Linh, in fact, had been employed under the program.

The plans have yet to be finalized, but the proposals include allowing trainees to transfer from one employer to another so long as it is within the same business category, as well as giving workers a chance to upgrade their skills so they can move on to the Specified Skilled Workers (SSW) Program, which offers better pay and a longer stay in the country.

The draft proposal that was drawn up by a panel of experts called for the “prevention of human rights abuses,” but did not specify how this is going to be done. A final report is due in the fall.

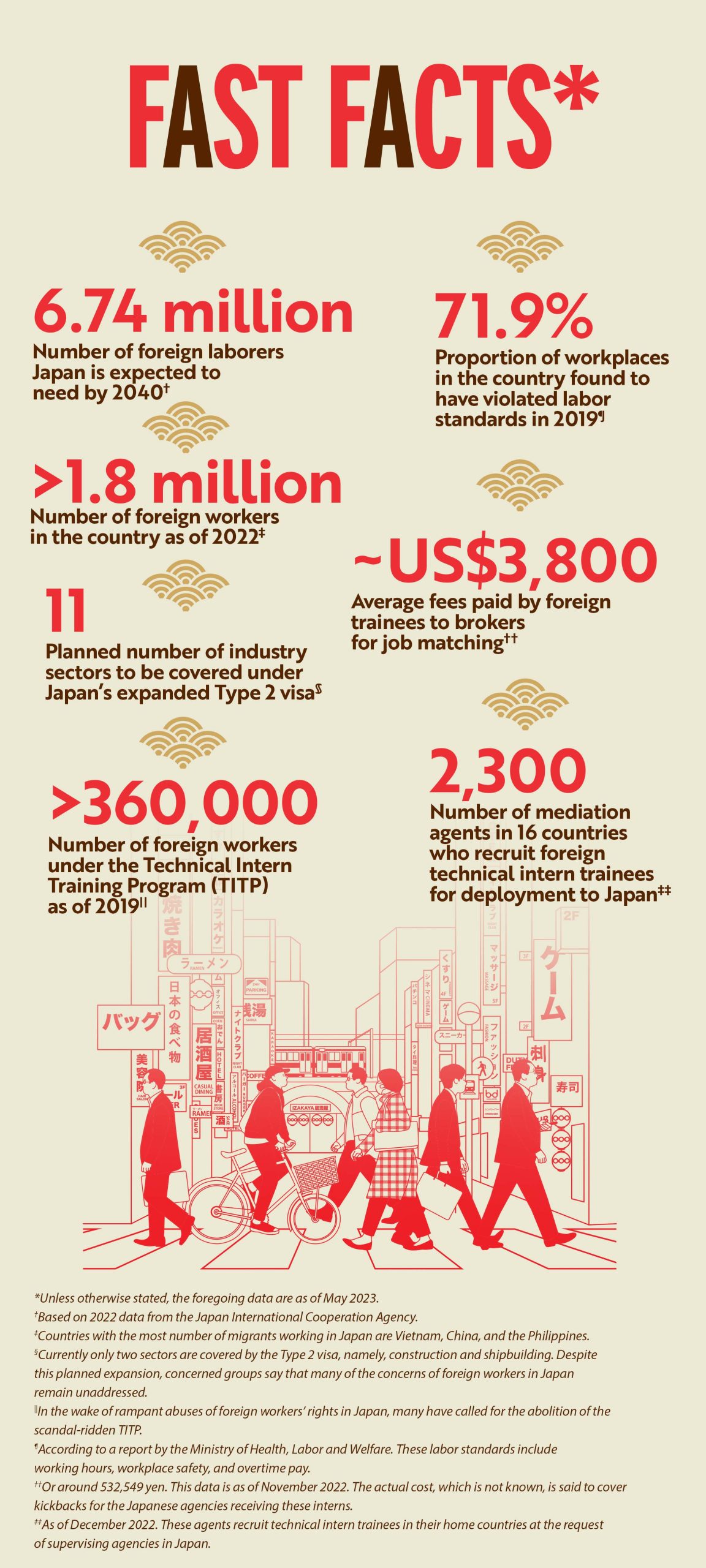

There have also been talks for sectors covered by Type 2 working visas to be increased from two to 11. Type 2 visa holders can stay in Japan indefinitely and bring their families to the country. Currently, Type 2 sectors are limited to construction and shipbuilding.

Activists say that while the proposals so far address the need for workers of a growing number of sectors in Japan, much of the concerns of foreign laborers have been left by the wayside. They also note that the current TITP has measures to prevent abuse, but most of these have failed to protect the foreign workers.

“The government is trying hard to be an attractive destination for foreign workers,” says Shinichiro Nakashima, spokesperson of the Kumustaka Association for Living Together with Migrants, a non-profit based in Kumamoto city in Kyushu, Japan’s southern main island. “There is a lot of work to be done before that.”

Running out of workers

For decades now, Japan has been grappling with a graying population and a shrinking birthrate that have combined to create an ever-worsening labor shortage. This has led to Japan grudgingly opening up to workers from abroad.

But Japan could be sprucing up its incentives for foreign workers since it is now up against stiff competition. According to a report from the state think tank Japan Center for Economic Research, nearby South Korea and Taiwan, as well as nations in the Middle East, are also looking to beef up their respective labor forces with migrant workers. Chinese technical interns in Japan have already fallen in number since 2012, it said, because they want higher pay.

As of end-October 2022, Japan had more than 1.8 million foreign workers, among whom more than 60 percent came from just three countries: Vietnam (462,384), China (385,848), and the Philippines (206,050). More than a quarter of the workers were in manufacturing, while 13 percent were in wholesale/retail, and 11.5 percent in hospitality and food services.

The total number of foreign workers as of end-October 2022 was 5.5 percent higher than the comparative figure a year prior. Foreign workers under the TITP also made up 18.8 percent of the total, or more than 340,000.

Introduced in 1993, the TITP is supposed to be one of Japan’s ways of transferring technology to developing countries through the employment of their citizens. But the program’s critics say it is actually meant to provide cheap labor for Japanese companies facing a shortage of workers.

“The Japanese government is not actively protecting the young trainees,” says Reiko Aoki, executive director of the Center for Health and Rights of Migrants or CHARM, based in Osaka, Japan’s second largest city. “The TITP represents modern slavery.”

Indeed, while the program includes supervising organizations that placed the trainees in companies and were supposed to monitor how they were being treated, abuses including unpaid overtime work and maltreatment have been rampant. Japanese law also stipulates equal treatment of Japanese and foreign workers, yet work-related injuries, lack of holidays, and conditions such as not being able to change work places and being laid off for being pregnant — are rife among the latter.

Surveys carried out by the Immigration Agency between 2017 and 2020 revealed that only 11 out of the 637 women who stopped work after getting pregnant were able to return to their jobs. The same survey also recorded that almost 28 percent of trainees were told by the mediating organizations that they should quit if they got pregnant; some had signed papers in which they agreed not to get pregnant before leaving their homeland.

Citing a 2019 report by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW), an East Asia Forum article posted in July 2021 also said that “71.9 percent of workplaces (had) violated the country’s labor standards regarding working hours, workplace safety, and overtime pay.” This was despite the government establishing in 2017 the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT) as another body that would oversee how the trainees are doing and prevent abuse.

Remarks Kumustaka’s Nakashima: “Migrants do not speak Japanese fluently and are unaware of the local laws, putting them at the mercy of their Japanese employers who view them as cheap labor.”

Left fending for themselves

As it is, OTIT itself has come under fire for being unresponsive or refusing to help foreign workers in crisis. According to a 2022 Kyodo News report, a Cambodian trainee who had gone unpaid by his employer sought but failed to get OTIT’s help in finding temporary shelter. A trio of Vietnamese female workers, meanwhile, were told to quit the labor union they had joined before OTIT would consider their request for help in dealing with their employer.

CHARM’s Aoki says that more often than not, TITP conditions are not followed by the employers while supervisory organizations and the TITP are understaffed and do not have much of what is necessary to check on the trainees. But she concedes that the problems of many TITP workers begin even before they leave their home countries, where they incur huge debts just to get employed in Japan.

Linh, for instance, took out a loan equivalent to JPY 1.5 million (around US$11,000) from an organization back in Vietnam so that she could be part of TITP. She sent 75 percent of her monthly wage of JPY 120,000 (US$883) back home to pay for it in installments and also help out her parents. She had already been working at an orange farm for two years when she learned that she was pregnant. Still in debt and fearing she would be sent back to Vietnam if she told her employer, she kept her pregnancy a secret.

Court documents say that she was all alone when she delivered her stillborn twin boys. Authorities found them the next day wrapped in a towel and inside a cardboard box that also contained a note saying, “I am sorry, my twin babies. May you soon find a peaceful resting place.” The box, which was inside another sealed cardboard box, had been placed on a shelf.

Linh was arrested for allegedly abandoning the corpses. But defense lawyers argued she had stayed at home with them all night and had even given them names. She ventured out the day after only to see a doctor, who she told about the stillbirth. A three-month prison sentence, suspended for two years, had been hanging over her head when the Fukuoka Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s ruling.

While her appeal was being heard last February, Linh had said at a press conference, “I hope I will be acquitted for the sake of foreign trainees who, like me, are suffering because they are unable to tell anyone about their pregnancies.”◉