|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

S

ana Tanveera says that she has recovered, but she still looks weak and her skin has a yellowish tinge. Just a few days ago, she had a high temperature and diarrhea, which the doctors said was due to typhoid fever. She should have been attending classes at her university, but her illness has had the 22-year-old going repeatedly to the hospital instead. Worse, Tanveera says that it isn’t only her, but the rest of her family also suffer from typhoid fever and other waterborne illnesses from time to time.

Tanveera and her family live in the Mengri area that is near Shakar Garh, some 161 kms northeast of Lahore, the capital of Pakistan’s Punjab province. The Tanveeras suspect that their frequent bouts of fever and diarrhea are due to the tap water that they drink. Unfortunately, they are probably right.

Dr. Muhammad Riaz, who works in a government hospital in the area, says that in the last few years, cases of those falling ill due to drinking dirty water have been increasing day by day in Pakistan. The most common waterborne diseases, he says, are typhoid, cholera, and stomach problems.

Clean water is the right of every citizen, Riaz says, but people in Pakistan’s impoverished areas in particular are deprived of it. “Due to unsafe water,” he says, “lives of children are at more risk because they develop parasites, worms, cholera and stomach bugs more quickly.”

For decades, Pakistan’s national government and local authorities have been launching one program after another aimed at providing clean water to the people. In 2018, the central government even made water as its top priority in its list of issues to be addressed. Yet that declaration was never really acted on, while policies and programs regarding water and sanitation across Pakistan have either remained on paper or been abandoned after a few years or so, with detrimental consequences.

In the area where the Tanveeras live, for example, the local government began a program in 2005 to provide safe drinking water to the 800,000 people there. It spent thousands of dollars to build 36 water-filtration plants (WFPs) for which monitoring committees were set up. But the plants remained functional only for so long and the committees supposed to be responsible to keep them working are now nowhere in sight. Local officials also admit in private that about the only water they check in the area would be the contents of bottles of what are supposed to be purified water from Nestle. (Some traders reuse empty bottles of the popular brand and fill them with tap water.)

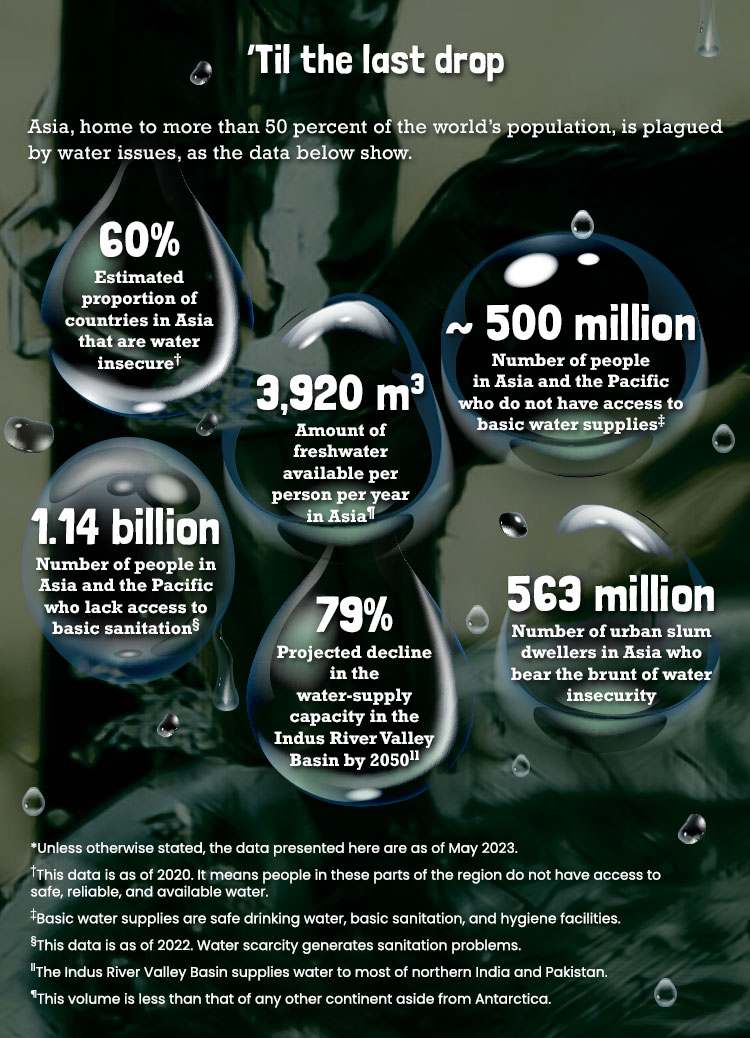

Today GlobalWaters of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) says that only 36 percent of Pakistan’s population of 238 million have access to “safely managed water.” An October 2022 study by Pakistani researchers on the country’s water sanitation problem meanwhile said that only 20 percent of Pakistanis have access to “quality water.”

“As a result,” said the researchers in their paper that was published in the Annals of Medicine and Surgery, “the remaining population is left with substandard quality water to fulfil daily requirements, undoubtedly exposing them to many diseases and other toxic effects of contaminated water, aggravated by anthropogenic activities.”

The situation has led to the loss of millions of lives. Noted the researchers: “In 2017, 2.5 million deaths due to diarrhea were reported in Pakistan; 50 percent of the country’s diseases and 40 percent of deaths occur due to consumption of contaminated water.”

In complete denial?

Corruption, poor planning and management, and what appears to be utter disinterest by both national and local authorities in the matter have been blamed for the dismal state of Pakistan’s water supply. An engineer who works on public projects in the Tanveeras’ community, for instance, tells ADC that the “government has failed to provide budget for the reconstruction of these filter plants as providing safe water and it’s still not its first priority.” He says that they have asked local officials “again and again (for a budget for it) but nobody is interested in taking the request seriously.”

Queried about the contaminated water in the area, a district municipal council official says that municipal committees all over Pakistan have high bills and that has meant that they do not have enough money to address every concern. The official also declares that they “try to fix everything but people should have responsibility also.”

He is unclear about what that personal responsibility should be, but trying to make contaminated water safe when one is left to one’s own devices isn’t exactly easy. Comments general practitioner Dr. Sadiq Maihi on one of the usual ways that people try to sterilize water for drinking: “Boiling tap water in Pakistan is not practical to remove all the germs. Sometimes it removes only a small fragment or works on micro level. Moreover, if tap water contains sewage, bacteria, sand, and arsenic, boiling it doesn’t purify it at all levels. It is like drinking warm, dead germs. For drinking water to be safe and healthy, you need to purify it at all levels. And that is why filtered water is more healthy than home-boiled water.”

For sure, boiling the water supplied to one of Lahore’s industrial neighborhood would not make it free from lead. Doctors conducting a medical mission in Shadipura in late 2021 had noticed that many people there had common complaints of chest and abdominal pain, as well as fatigue. A report on the case by The News online publication a year later also described the patients as having blackened gums and teeth, and experiencing difficulties in coordination and balance.

Tests conducted on some children from the community confirmed that they had lead poisoning, which was traced to the water they had been drinking. According to The News, “it was determined that industrial waste” from the iron foundries nearby had contaminated the water and soil in Shadipura. Yet the media outfit quoted Dr. Nausheen Zaidi, whose team had collected samples from the community’s drinking water as well as the soil in Shadipura, as saying: “The water regulatory bodies are in complete denial of the crisis. They claim they have inspected their water reservoirs and not detected any contaminants. They doubt our test results.”

A wet mess

Water piped into homes is usually provided by the government. In the case of Shadipura, it was and is the Water and Sanitation Agency providing the community its tap water. In other areas, some households have resorted to deep-well pumps for their water supply. But that has not meant they are getting water that is any safer from the rest of that of the community. At the very least, the researchers of the October 2022 study pointed out that untreated groundwater in Pakistan is high in saline content.

The practice of open defecation that is still prevalent in many communities across the country is among the more common causes of contamination of water sources in Pakistan. The increased instances of flooding have also contributed to water pollution, with floodwaters causing sewage and poisonous chemicals from damaged structures spilling into water sources. In addition, there is the improper handling and disposal of industrial and agricultural wastes that include highly toxic substances such as arsenic and, yes, lead.

Dr. Zaidi said that they are considering litigation to right some of the wrongs done to the people in Shadipura. The residents themselves have indicated that they want the local government to put up water-filtration plants. Should their request be granted, though, the Shadipura residents may have to consider volunteering to see to the upkeep of such plants.

Just eight years ago, the Punjab government had participated in the Clean Drinking Water for All (CDWA) project of the national government. It built 307 water-filtration plants in all in Lahore, Kasur, Okara, and Bahawalpur, with the equipment imported all the way from Germany. But after only a few years, many of the plants had already fallen into disrepair. Apparently, they were not maintained regularly, and there has been little indication that water quality in these areas came under inspection even periodically.

These were echoed in the 2018 evaluation report on the CDWA that had been implemented in Balochistan at the same time as the one in Punjab. According to the report, only 40 percent of water-filtration plants in Balochistan remained operational just three years after they were put up. The rest were “out of order or non-functional.”

The report also said that of the 19 (out of 47) plants that were operational, users of 15 of these facilities complained of “insufficient plant operation time, resulting in unmet demand for clean water.”

“In cases where the plants operate flawlessly, the users considered the intervention vital to improving the health of the community, a positive outcome of the initiative,” the report observed. “However, a weak success rate with many non-functional WFPs undermines the notion of beneficial impact.”◉