|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

n a region where autocrats take power far too easily and frequently, Mongolia has been a curious outlier. Since 1990, when it made a peaceful transition from communism to democracy, Mongolia has embraced and upheld the democratic values of free elections and media freedom while protecting other human rights. And while the country is sandwiched between two autocratic superpowers, its democracy has withstood the test of time. During an official visit there in 2016, then U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry even praised Mongolia as an “oasis of democracy.”

Mongolia’s strong constitution has been said to be a large factor in democratic values flourishing in the Central Asian country. Yet that may soon change as the people who are supposed to uphold the charter are now seen as attempting to demolish it.

Legal experts and rights advocates alike have been up in arms over moves to amend the country’s constitution. They say that the timing is suspect, as the moves are being made when those in power are experiencing an all-time low in popularity. Moreover, they point out, the public has been left mostly in the dark about what precisely the amendments are.

On 2 February, Parliament issued a statement saying that, at the moment, there is no proceeding to amend the constitution — even as charter-change proponents say this is needed to stabilize Mongolia’s democracy. But there is a government-formed working group to draft amendments to the charter.

In a press conference last 26 January, former President Enkhbayar Nambar, who is part of that working group, said, “The Constitution adopted in 1992 was very important. We transitioned from a party-centered to a state-centered social agreement.”

“We’ve had this system for 32 years,” he continued. “Unfortunately, the government is now out of control as a result of this system. People are irritated by this type of government. As a result, there is now a call for a people-centered constitution in which citizens have control over the government. This is mirrored in the recently drafted new Constitution.”

Enkhbayar then said that he had distributed the draft to all foreign embassies in order to demonstrate to foreigners that Mongolia is not a communist society, but is guided by a constitution that respects human rights. Interestingly, Foreign Affairs Minister Battsetseg Batmunkh notified embassies shortly thereafter that the document from Enkhbayar did not officially reflect the position of the Mongolian government. To some observers, however, all that public bustle may have been aimed at floating the idea of charter change in the public sphere, and not for good reasons.

Legislative express train

For sure, no draft of any sort has been made available to Mongolians themselves. The only clue that they have on what the changes could be is the ruling of the constitutional court in August 2022 that said the 2019 constitutional amendments limiting parliamentarians and cabinet members to four seats were unconstitutional. This, say legal experts, essentially reverted the charter to controversial changes made in 2000 by the then Mongolian Parliament and which had been deemed corrected by the 2019 amendments.

National University of Mongolia law professor Gankhurel Damba says that the only reason the court would revert to the unpopular amendments of 2000 is political. Or as he put it, “The recent decision was one that politicians needed.”

Indeed, many Mongolian scholars and legal experts regard the court’s decision as a step back in Mongolian democracy. They argue that the court has no right to make recommendations to change the constitution; its job, they say, is to interpret the law, not to make recommendations on whether the constitution is right or wrong.

After the court released its ruling in August, Parliament quickly convened an extraordinary session to amend the constitution. Just two weeks later, on 25 August, the legislature approved new constitutional amendments to allow more MPs to hold cabinet positions. On 30 August, it also appointed 10 new Cabinet members, and then three more last 5 January.

Lawyers such as Galbaatar Lkhagvasuren say that this only proves that the constitutional court’s 15 August 2022 decision had simply brought back the 2000 constitutional amendments. Among other things, Parliament had decided in 2000 that MPs could also serve as ministers, giving rise to the term “davkhar deel,” referring to officials taking on positions in both the executive and legislative branches.

Davkhar deel was unpopular during the years it was in practice and now it is back. Explains Galbaatar: “When you have MPs serving as cabinet members, and when certain decisions are made in parliament or cabinet, we can’t tell if the decision is coming from the government, or is it on the agenda of parliament?”

Charter changes

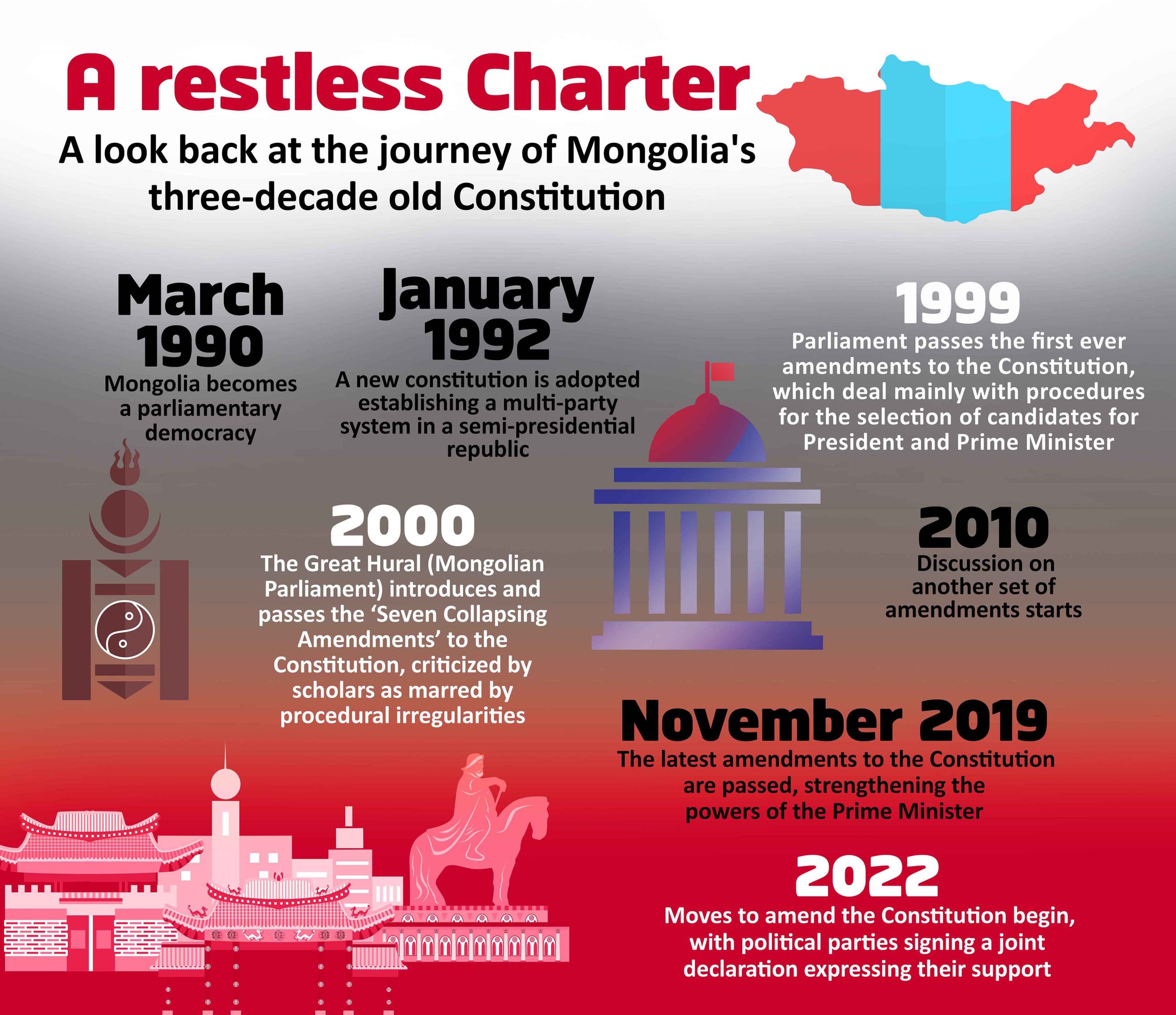

The Mongolian Constitution was drafted between 1990 and 1992 by a 20-member multi-party Constitutional Drafting Commission chaired by then President Ochirbat Punsalmaa, with prominent lawyer Chimed Bayaraa serving as Secretary. The draft was tackled four times by the Baga Hural (now defunct lower parliament), discussed in public for three months, debated for 70 days by the Great Hural (Parliament) at the end of 1991, and finally promulgated on 13 January 1992. According to the 2016 UNDP Assessment of the Performance of Mongolia’s Constitution, the charter is one of the most stable in the world.

The constitution is not without flaws, however. Some Mongolian lawyers say that parts of it are among the reasons why Mongolia has created a clientist political system in which legislators and government officials have been able to enrich themselves, their cronies, and favored businesses. Mongolia’s wealthiest people, in fact, are now in government or have previously held legislative power.

Then again, unlike other former Soviet republics that became independent and democratic but failed and have become autocratic, such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, Mongolia appears to have kept its young democracy intact because its constitution ensured some form of rule of law, as well as an independent judiciary that interpreted the charter as it was written and was unswayed by political powers. That is, before the constitutional court’s recent ruling became known to the public.

When the charter was first amended in 2000, legal scholar Gunbileg Boldbaatar said in a 2017 paper, the changes “were not made in accordance with the proper constitutional procedure and were not based on the fundamental principles of the Constitution of Mongolia.” Notably, too, the 2000 amendments had been adopted behind closed doors without public debate.

Many said later that the changes weakened the separation of legislative and executive powers. Gunbileg himself observed: “These 2000 amendments caused instability of government in Mongolia and misbalanced control of governance authority. The amendments led to the condition that irresponsible decisions of (the) Government of Mongolia could not be easily controlled or restricted.”

In contrast, the 2019 amendments were arrived at via the participation of scholars and a broad selection of citizens. The draft also took three years to complete before being voted on in November 2019. The second set of amendments included a slew of provisions that not only separated legislative and executive powers, but also strengthened the government cabinet, as the country had previously suffered from administrations that lasted an average of two years each. It weakened presidential executive powers, which had been gaining more sway over judicial governance; this brought the charter back to its 1992 incarnation, which had reflected its authors’ belief that a single executive power would be detrimental for a country like Mongolia.

From talks to quick action

Talks of amending the constitution again, however, began swirling in June 2022. The main objective seemed to be to increase the number of members of parliament from 76 to at least 140, as well as to create a lower chamber of parliament. A few weeks later, Prime Minister Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai issued an order establishing a working group under the government to draft constitutional amendments. After only one month, Parliament, with the assistance of the constitutional court, amended the charter, including provisions not mentioned in the June talks.

The court ruling is reminiscent of what political scientist Javier Corrales calls “autocratic legalism,” a version of which has been seen in Venezuela: a body that was supposed to protect the constitution is now the entity that would dismantle it for the benefit of the ruling party and not the people.

Yet while the ruling Mongolian People’s Party (MPP) may not be facing any challenges from all three branches of government over its plans for charter changes, it may have a harder time convincing the public about the move. Just last December, Mongolia saw the second largest protest movement yet in the country over the coal-theft scandal that had many youths demanding accountability from those in power.

Still, it could well be that the MPP is feeling very confident it can pull it off, with or without public approval. A few days after the protests ended, the party held its conference online. There, it gave Prime Minister and MPP Chairman Oyun-Erdene authority to change the current parliamentary system and amend the Constitution.

Some observers suspect that the new Protection of Human Rights on Social Media law would be used to silence critics during elections and possibly during the processing of new constitutional amendments. Rights groups say that the social-media law actually undermines freedom of expression in Mongolia while masquerading as a measure to protect children online. The bill had been rushed through parliament and passed within two days of its introduction. It was supposed to go into effect on 1 February, but a full presidential veto on 30 January has now forced it to be debated in Parliament during its spring session, which will take place after Mongolian Lunar New Year (21-23 February).

One institution can stop its implementation: the constitutional court. But so far it has kept mum on the matter.◉