|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

t was the 30th anniversary of the official start of diplomatic relations between South Korea and Vietnam, and a special tournament for businessmen from both countries was being held to mark the occasion at Hanoi’s Long Biên Golf Course. In attendance at the extravagant opening for the event last May 2022 were politicians and business leaders, as well as some members of the media.

About 20 Vietnamese enterprises based in Hanoi and neighboring cities were invited to showcase their merchandise at the luxurious gathering. Thanks to her connections, a 60-year-old businesswoman who wants to be identified only as “Nguyễn” was also able to attend and network with wealthy and well-connected people who could help market her brand. According to Nguyễn, many businessmen had paid the event’s organizers to be given slots. But she was lucky to be there at no expense from her end — at least, not in the form of a fee.

In fact, when one of the official guests — a high-level party leader from Hải Phòng, one of the five centrally governed cities in Vietnam — visited her booth, she showered him with several of her latest products.

Nguyễn declines to divulge just how much those gifts were worth. She does say, however, that she considered them as an “investment,” and that she had given a journalist covering the event a “generous gift” to help her sniff out who would be “big fishes” in the room and who would, based on his judgment, elevate her business to a higher level. It was actually no accident that the high-level party official approached her booth.

Befriending and bribing journalists to access information to her own advantage is among her business tactics, Nguyễn says. Paying media people is part of her business costs, or what she calls “diplomacy fees.”

According to Nguyễn, she was not the only entrepreneur at the event who benefited from the insight of the journalist she befriended “via money” that night. More often than not, she says, media workers would know the ins and outs of each event. On that day, the journalist she connected with also introduced her to a family member of another powerful person. Nguyễn quips, “Journalists excel at multitasking.”

Another power of the pen

While many Vietnamese journalists have been attacked or jailed for speaking inconvenient truths or exposing corruption, several of their colleagues are often catalysts for such wrongdoings. With meager salaries at state-owned outlets and faced with tight restrictions on what to cover, more and more Vietnamese journalists are choosing to use their pens and keyboards to “help” businesses and state agencies and officials in exchange for money and other benefits.

“You can bribe them in different ways, and not necessarily with envelopes,” says Thành Công, who runs a small business in Hanoi. “Treating them to an expensive meal can be a great start.”

“You can bribe them in different ways, and not necessarily with envelopes,” says Thành Công, who runs a small business in Hanoi. “Treating them to an expensive meal can be a great start.”

A state media-affiliated junior staff writer in Hanoi admits as much. Requesting to be referred to only as “Quang,” he says that with their low salaries, Vietnamese journalists like him need other sources of income, including bribes from businesses, just to survive. Quang says that among his income sources is from attending events, where journalists are paid “attendance fees.”

These include events organized by state agencies. A retired civil servant who wants to be called “Thuỷ” says that envelopes for journalists are part of “guest-receiving fees” in her former workplace.

“If you do not ‘gift’ them, they will not write an impressive article about your activity,” says Thuỷ. “Gifts preempt them from writing (anything) against you.”

According to Thuỷ, journalists don’t need to paint any negative picture to put an organization’s reputation at risk. She says, “Writing simple and straightforward articles might be enough to ruin careers of many civil servants.”

Like other journalists interviewed by Asia Democracy Chronicles, Quang says that he knows what he is doing is unethical. But even those who choose to keep clean say they turn a blind eye on what their colleagues are doing because they understand that it could be a matter of not having enough to live on.

“If I did not moonlight, I would not be able to make ends meet,” says Quang, who also works as copy editor for several companies.

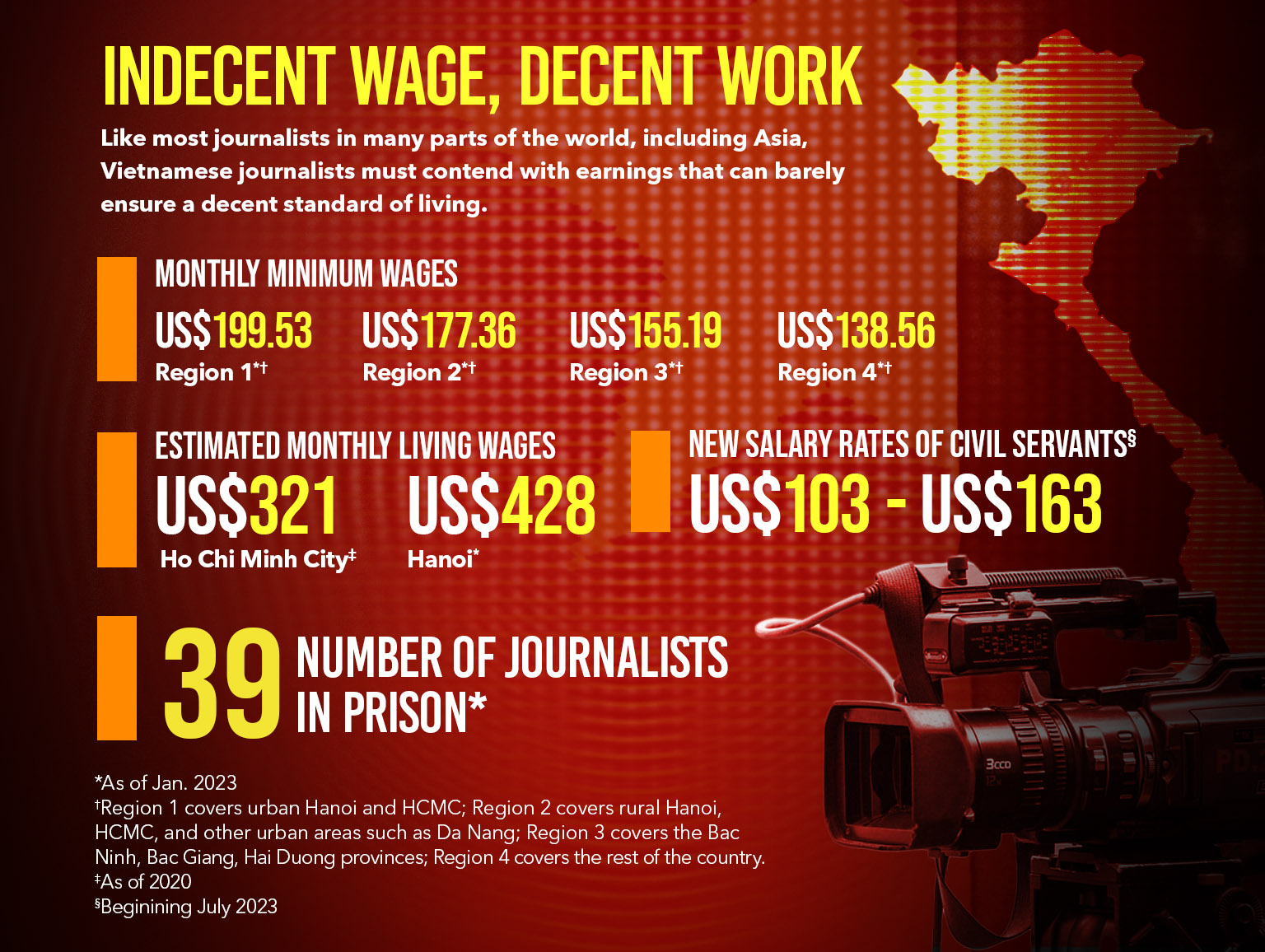

Quang’s monthly salary is VND 8 million or US$340 before tax. And that’s only if he is able to meet a monthly quota of at least 20 articles with a minimum of 1,000 words — which means he barely has a day off.

Quang’s wage is equal to the standard monthly salary for mid-career civil servants, many of whom live with their families. On average, though, one would need at least VND 10 million (US$428) a month to survive in Hanoi. Quang, who lives alone, shells out VND 2 million (or around US$85) a month just for the rent of his small apartment. He is not reimbursed for expenses he incurs while doing his stories.

Discouraging do-gooders

But it isn’t only financial need that seems to be driving Vietnamese journalists toward the dark side. It may also be due to the fact that doing their jobs right either gets them nowhere at all or in trouble with authorities.

In Vietnam, all mass media organizations are under the direct control of the Central Propaganda and Training Commission, which in turn is under the Communist Party and the Ministry of Information and Communication. Officially, there is no such thing as a private media outfit in the country. Websites run by private organizations and have journalistic characteristics are referred to as “information-conveying channels” and are not authorized to produce original content.

Journalism in Vietnam serves primarily as the mouthpiece for the Party and State by advocating positivity, success, and stability. Then again, publishing negative reports on government officials — much more private firms — is supposed to be officially accepted. After all, to serve the Communist Party’s anti-corruption cause after the sweeping socio-economic renovation known as Đổi mới in 1986, state-owned media outlets were given the green light to report corrupt activities.

It is an open secret that corruption is rampant across the state sector. Many state authorities are rumored to be corrupt, and are categorized as either “the exposed” or “the-not-yet-to-be-exposed.” Many private businesses meanwhile commit wrongdoings and resort to bribery, among other things, to get away with these.

Yet even if a journalist were to write about the breaking of laws of public officials and private businesses, there is no guarantee that such stories would make it past the editorial gatekeepers. Or if these do get published, they would not get deleted quickly.

Retired civil servant Thuỷ recalls the time when a state media outlet ran a story about the chief at her agency. The article had noted how two months before he retired, the chief had begun appointing people to a number of positions at the agency. Says Thuỷ: “Those familiar with the state sector would understand immediately why an outgoing leader has to appoint many positions on the double: Because each appointment is accompanied by bribes. As the person was going to retire, it would be his last chance to pocket bribes.”

Upon solicitation and gifts from the state agency, however, the journalist in charge agreed to have the article deleted.

Sentenced for Facebook posts

Some journalists have turned to Facebook to tell their stories about corruption that would otherwise not see the light of day. Jail time can be among the consequences they would have to face for such Facebook posts, however. In April 2022, former Bao Phap Luat TPHCM journalist Nguyen Hoia Nam was meted a prison sentence of three and a half years for Facebook posts in which he wondered why only three minor bureaucrats were charged in a corruption case at a state utility agency when he had clearly identified 15 people as having allegedly taken bribes.

Reporters Without Borders also says that during the same month, Phan Bui Bao Thy of the state-owned magazine Giao Duc va Thoi Dai was meted a sentence — albeit a lighter one — as well. For several Facebook posts alleging that the culture, tourism, and sports deputy minister was involved in corruption, Thy was ordered to receive a year of “non-custodial re-education.”

It’s no wonder then that there are Vietnamese journalists who just throw up their hands and let themselves get swept by the tide of corruption. Businessman Thành Công, however, says that one still needs to tap personal connections to be sure a journalist would cooperate and not turn around and report to authorities later.

He recounts how he sought out and paid a journalist from a state media outlet to write a story that would help boost his business. According to Công, he secured the reporter’s contact through his circle of friends.

“When she came, I told her what to write because she did not ask any questions,” says Công. He adds that he chose a not-so-well-known outfit in order not to spend a huge amount.

Journalist Quang, for his part, says that one does not need to search high and low for scandalous stories involving private businesses. His medium-sized media employer, for example, receives a lot of emails and phone calls from readers informing it of business violations, the most common of which are the misappropriation of public space and misuse of residential land.

When journalists go out on field to fact-check these reports, he says, businesses would often offer “hush money” so that the media outfit would go soft on them or be totally silent on the issue. But journalists and their media employers would consider accepting such offers only if they are familiar with the benefactor or if they fear turning the money down could become a mark against them.

In truth, media outlets can benefit financially from publishing stories about corrupt companies. While media outfits refrain from running stories about wrongdoings of big firms that are politically well-connected, those committed by small and medium-sized businesses are fair game. A junior reporter in Hanoi says that her editor encourages them to look for negative stories or those about wrongdoings because these can attract readers. Says the reporter: “If we attract more views, we will receive more state funds and advertising contracts.”

But Quang says that journalists themselves might also reach out to errant businesses and offer to gloss over negative issues involving them in exchange for fees.

“Unfortunately,” he says, “pens can be bent by money.”◉