|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

he latest story on drug use among young people in Myanmar seemed more fantastic than the previous one, so journalist Ko Aung (not his real name) decided to see for himself what was going on. For several days and nights, he visited nightclubs, karaoke bars, and schools that were said to be drug buying-and-selling hot spots in the business capital Yangon. His bad news: Buying illegal drugs has indeed become “as easy as buying candy” in Myanmar.

“You will look out of touch if you don’t use drugs,” says Ko Aung. “It is nothing strange to use drugs at parties and clubs. Youths go to parties and use drugs. This is trending.”

Nearly two years after the military seized power in February 2021, drug use is on a steep rise in Myanmar, especially in Yangon. But while that seems to indicate a breakdown in law and order under the junta, some observers on the ground and analysts abroad see it more as a deliberate development instigated by the country’s military leaders.

They say that the junta profits financially from the drug trade in which state actors are both directly and indirectly involved and also benefits politically from having Myanmar’s youths so caught up in narcotics that they no longer have the energy to stage protests.

According to political analyst U Than Soe Naing, among the junta’s tactics for staying in power are propaganda movies, entertainment, and drugs. He says that leaders of the military use the drug business systematically for their political gains.

“They [military authorities] make it easier for drug sellers and drug users,” says U Than Soe Naing. “The prices of drugs have decreased. They don’t crack down on drug trafficking effectively. They intentionally ignore it.”

U Pe Than, a veteran Rakhine politician and former member of parliament, agrees. “Drug usage among youths is big news,” he says. “So, they [military authorities] should be able to control it. It is their responsibility to manage and crack down on drug usage.”

He notes that the youth, especially those of university and college age, were targeted in particular by previous military governments, such as those under the late General Ne Win and ex-junta chief U Than Shwe. Authorities then even relocated and built universities and colleges outside cities to control students effectively and prevent any attempts to organize protests.

Powerful ties

The implication is that the military can limit, if not stop, the spread of drugs among the youth — if it wanted to. One reason why the junta is barely lifting a finger against the disturbing trend these days, says U Pe Than, is that “children or family members of the junta” are in the drug trade.

“They use it openly in bars and clubs,” he also says of the children and other relatives of members of the military. “Nobody can stop them. Even law enforcement can’t stop them. When they say they are children of a military official, nobody wants to mess with them.”

Just this September, Thai authorities detained, under suspicion of drug trafficking, a Myanmar businessman described in media reports as the son of a retired lieutenant colonel. The businessman, in his 50s, is also allegedly a “close associate” of Myanmar junta leader Min Aung Hlaing.

Meanwhile, in an article published last January by the online publication GRID, Daniel Combs, author of the book Until the World Shatters: Truth, Lies, and the Looting of Myanmar, said that aside from gems and rare-earth minerals, drugs are also among the sources of income of Myanmar’s military.

Combs, who works for the U.S. State Department, wrote: “Privately, drug enforcement officials, international advocacy groups, and local researchers say that the (methamphetamine) trade — historically and in the past year — is one more significant source of off-book revenue for the regime, in the form of kickback payments and bribes paid to military figures.”

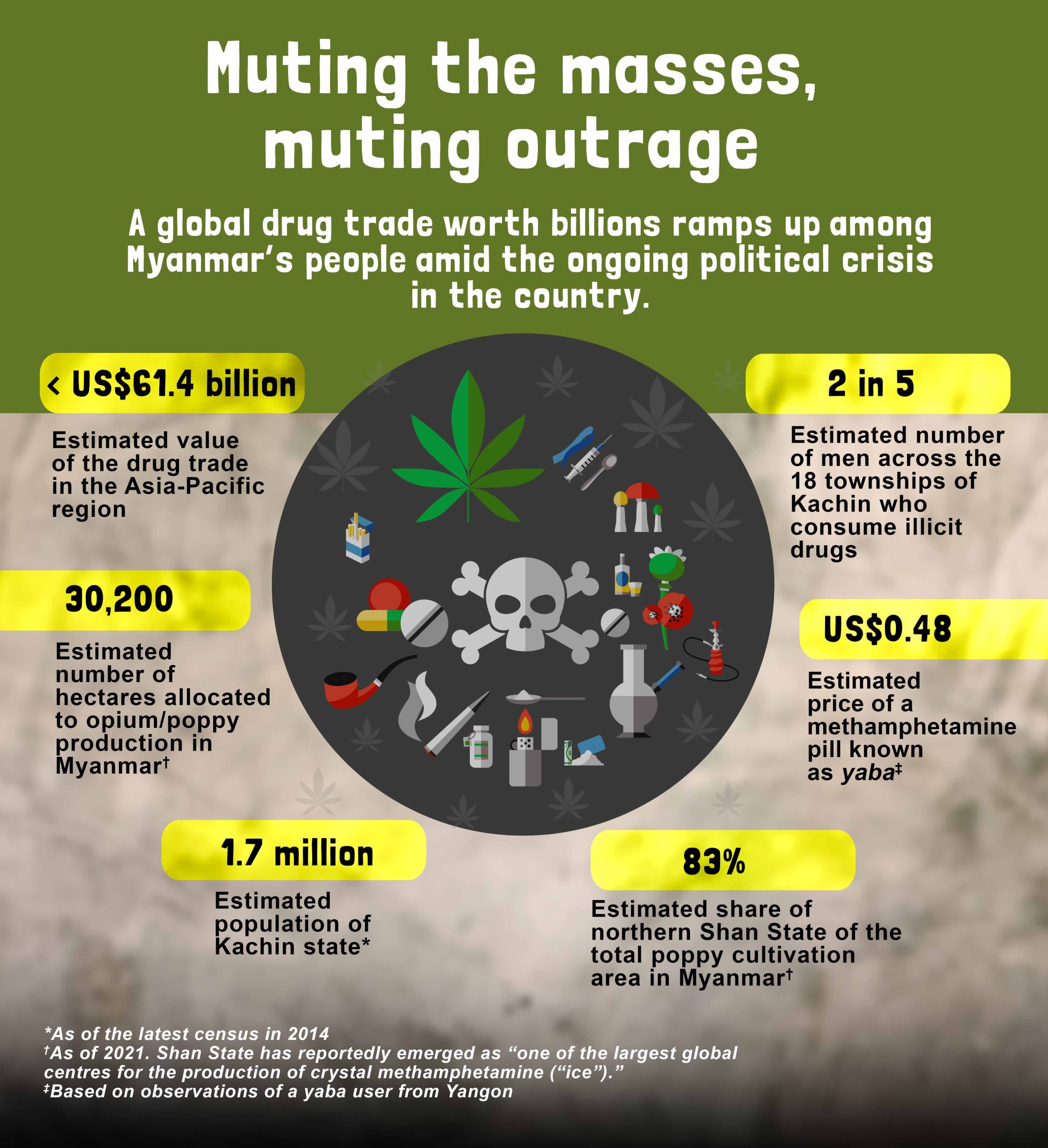

The majority of the drugs come from Shan State in the east and Kachin State in the north. Some of the drugs manufactured within Myanmar are allegedly controlled by the United Wa State Army based in Shan State bordering China. Other drug producers include Myanmar military-backed paramilitary groups in Kachin and Shan States that make stimulant pills, crystal meth, and heroin, among others.

The drugs are also exported to other countries, such as Thailand, Malaysia, China, Bangladesh, and elsewhere across the Asia-Pacific. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has estimated the drug trade in the region to be worth between US$30.3 billion and US$61.4 billion, with the bulk of the illegal substances coming from Myanmar.

As cheap as street snacks

Drug use is nothing new in Myanmar. But many point out that in the past, people did not dare to sell or use drugs openly or in public. Today some Yangon residents say that they see young people — even the preteens selling plastic bags near the Shwedagon Pagoda — taking yaba or caffeine-laced meth tablets on the streets.

One Yangon resident who declines to be named said that the drugs have become surprisingly inexpensive. He says that one yaba pill cost between MMK 8,000 (US$4) and MMK 10,000 (US$5) in 2010. The price went down to MMK 5,000 (around US$2.38) in 2015. But after the 2021 coup, a yaba tablet can be had for just MMK 1,000 (US$0.48).

Says the Yangon resident: “While commodities have seen extreme price increases, the price of yaba pills is unbelievably cheap. The price of the pills is just like that of snacks and betel nuts.”

“There were drug business deals made at bars and entertainment industries in the past,” journalist Ko Aung also says. “But it has gotten worse after the coup. At some bars, waiters openly sell yaba pills to customers. I witnessed it.”

A drug dealer in Yangon who requests anonymity says that military and police officers, as well as local administration officials, are often spotted in night clubs using drugs. They also show up as “protection” for the club owners and patrons. According to the drug dealer, these officials make money just for showing up at the clubs.

“A police officer makes MMK 1.5 million (US$476) per visit,” he says. “A club owner pays for the police officer just to visit and stay at the club because there is no crackdown or arrest if a police officer is stationed at the club. It is like he is on duty so nobody would mess with them.”

He says that some military officers in plain clothes and with pistols on their waists provide security for nightclubs such as Woodland Bar and Honey Nest in Yangon. The fact that such establishments close at two a.m. despite Yangon’s curfew of midnight to four a.m. only shows that they do not expect to be fined or punished even if they violate official rules.

Myanmar’s drug law also penalizes persons found guilty of drug possession with jail terms between five to 10 years and a fine. Government newspapers regularly report arrests of people for drug trafficking, asserting that those violating laws are prosecuted in accordance with the law.

Yet those who are privy to such matters say that while security forces have sometimes arrested drug users at nightclubs and bars, they release them the next morning. Club owners also “negotiate” for the release of their clients who are arrested.

The drug dealer even says that there are now places called “Hi” that specifically offer “drug services.” He says that these are mushrooming in Yangon, along with new KTV karaoke houses that have opened with the intention to offer similar services.

Lure and crush

According to the drug dealer, ecstasy or E and ketamine or K are bestsellers. There is also Item, which mixes E and K, to which is added Eric E, a drug in liquid form. One serving of Eric E costs MMK 50,000 (US$43); it is normally drunk.

K, by contrast, “is absorbed through the nose,” explains the dealer. “They [drug users] use ATM cards or plastic ID cards to crush K and make a line of the powder. They then use a straw or a new currency note to snort and absorb the drug through the nose.”

The Yangon resident who requested not to be named says that Woodland Bar has become notorious as the distribution hub of illegal drugs, but mainly yaba. He says the drugs from Woodland make their way to the other bars and entertainment places.

He also says that some young people have become drug brokers and sellers for their daily survival. They are no longer interested in politics and activism, the Yangon resident says. He believes that the current proliferation of drugs is a trap set up by the junta to lure the youth away from political activities.

“I strongly believe that the junta intentionally let the drug trade grow because they know that young people will not be interested in politics if they are addicted to drugs,” says the Yangon resident. “They don’t want young people to get involved in politics. Drug addicts become slaves of drugs. It is (the junta’s) strategy. They have been using this tactic in the past.”

An English-language teacher in Yangon also believes that the use of yaba in particular would not be as widespread as it is now without the authorities’ involvement. At the very least, the teacher says, the junta has intentionally turned a blind eye to the rising drug use among youths.

“The young don’t see a bright future and they feel lost, so they would go for drugs,” says the teacher. “The drugs will make them happy and relieved. They [authorities] know this. This is a good time to lure young people into drugs as many youths feel lost and frustrated.”

“Burmese military regimes don’t want youths to pay attention to politics,” continues the scholar. “So they destroy youths with drugs. Under the rule of military dictators U Ne Win and U Than Shwe, many youths ruined their lives by using drugs and becoming addicts.”◉