|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

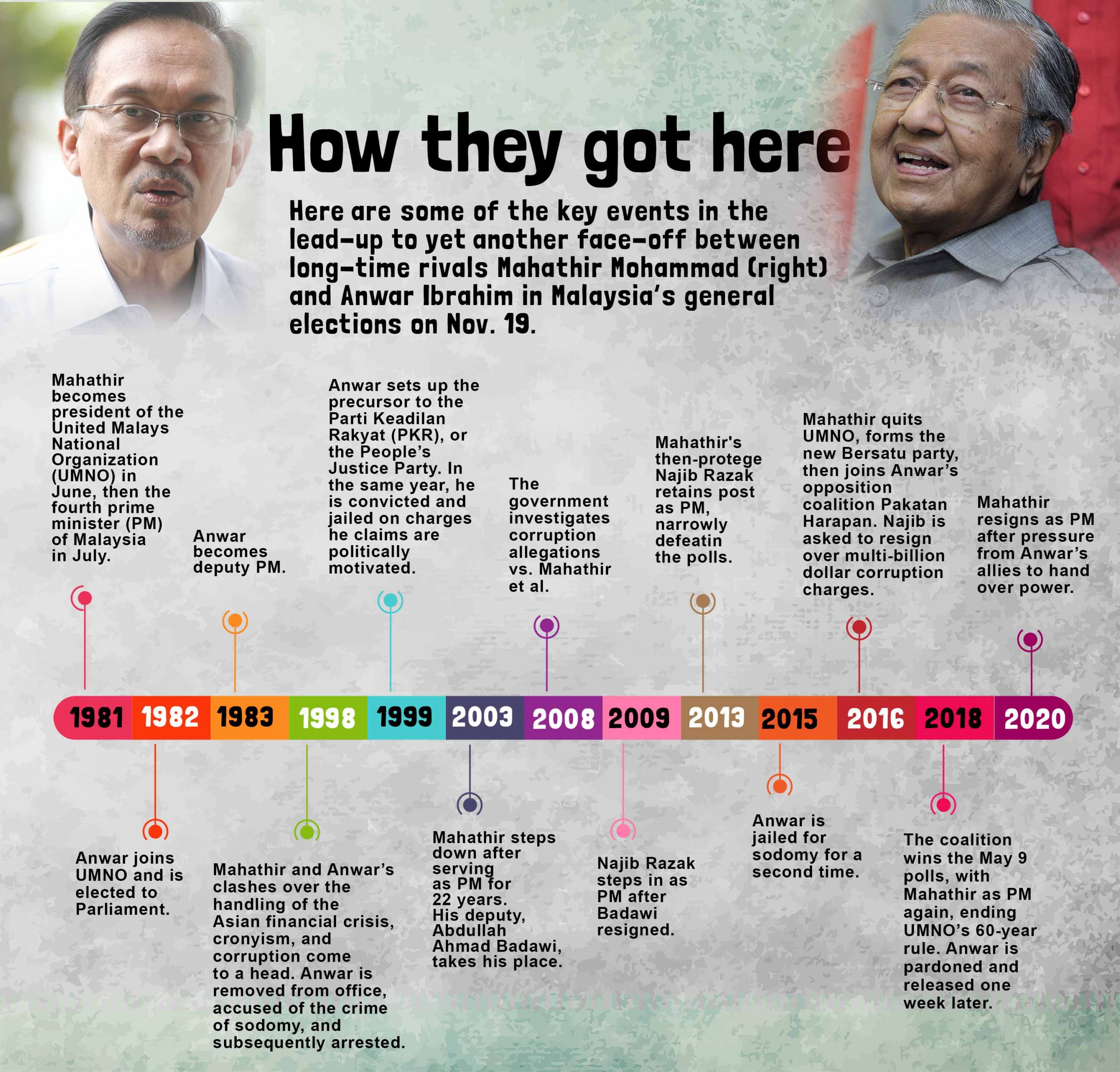

magine the longest-ruling and most-respected leader of a country running again for an election seat at the ripe old age of 97. And he is doing this just four years after he had teamed up with a former deputy in order to take down said leader’s chosen successor, who had been accused of embezzling state funds to the tune of MYR 2 billion (US$1 billion). They won and the corrupt leader is now in jail.

But the alliance between the long-time leader and his ex-deputy, Anwar Ibrahim — who had been imprisoned by the former for over a decade on trumped-up charges of sodomy — turned sour first, and soon broke up. Up next, leader and ex-deputy became heads of different coalitions that will be pitted against each other in a snap poll.

This might sound like the newest political television drama coming to you on Netflix. But it’s not. It is the unfortunate reality of the 33 million people living in Malaysia for whom truth is often stranger than fiction.

Since the 2018 Malaysian election when Mahathir Mohammad — the nonagenarian leader referred to earlier — came back to the fore, there have been three prime ministers (PM) in the space of two years in the Southeast Asian state. And on Oct. 10, the latest of these PMs, Ismail Sabri bin Yaakob, dissolved the Malaysian parliament a year ahead of the deadline, paving the way for a general election, and possibly another PM.

Sabri needed the consent of the King of Malaysia, or the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, before dissolving parliament. He got it, but a mere two hours after Sabri announced parliament’s dissolution, the king issued his own statement, where he expressed “disappointment at the political developments” and insinuated that the current legislature’s instability left him with “no choice but to consent” to its dissolution.

The king was accurate about the volatility of the current Malaysian government. The Barisan National (BN) or the National Front is a coalition of three major and numerous minor parties and has ruled Malaysia nearly without interruption since its independence. The coalition’s largest and most influential party is the United National Malay Organisation (UMNO), from which the PM is usually drawn. Mahathir himself was part of UMNO for most of his political career.

In 2018, BN’s decades-long hegemony was shattered when Pakatan Harapan, the opposition alliance, won a majority of seats in the election, coming to power in a wave of hope and optimism. But this was short-lived; the government was unable to push through any of the progressive promises it made during the election, eventually leading to BN’s comeback in 2021.

Power see-saw

The Malaysian state is inert for many reasons. One is that the old BN politicians are still very much in power, working behind the scenes to cripple the democratic government. During his tenure as U.S. president, Donald Trump’s ramblings about “deep state actors” who are actively working to topple him were dismissed as a conspiracy theory. In Malaysia, however, these older politicians and civil servants from the strongman-Mahathir era still exist within the state, making the move toward a more progressive government that much harder.

Dobby Chew, executive coordinator of the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network that is based in Kuala Lumpur, points to this as being a problem deep within the workings of the Malaysian state. “Malaysia has been an authoritarian state for 60 years,” he says. “And the old guard is still around. They are threatened (by democratic movements) and fear that they will be sidelined or imprisoned. Most of all, they are terrified of a progressive government that will bring reform to Malaysia.”

Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch Asia, agrees that the remaining UMNO civil servants are part of the problem. He notes, “Ever since the Pakatan Harapan coalition took power in General Election 14 in 2018, the long-time ruling party UMNO and its coalition partners never really accepted being the opposition, and they looked for every possible way to bring down the PH government.”

He continues by pointing the finger squarely at UMNO: “It’s like UMNO and its leaders could not really imagine that anyone but themselves should have the right to rule Malaysia, and they have been continually more interested in seizing back power, regardless of how much damage they cause to Malaysian democracy in the process.”

Several UMNO officials have faced or are facing corruption charges. The former PM who was charged with corruption, Najib Razak, is now serving a 12-year prison sentence, and his allies left in government are worried they will be next.

Malaysia also faces a see-saw power balance between a nationalist-conservative bloc and new progressives with a human-rights agenda. Malaysia has a large and vocal conservative religious community. These are not just Muslims but also Chinese Christians who are united in their opposition to LGBTQIA rights. The government elected in 2018 was forced to pander to the conservative right in order to stay in power, which led to the undermining of its own base.

To Chew, this inability to balance or mediate between these antithetical forces is one of the most fundamental reasons why Malaysia has not been able to keep a stable government since the 2018 election. The constant tension between the political spectrums has led to a debilitating stalemate in government, inevitably bringing up the question of legitimacy. The new PM might have legal legitimacy, but without political or moral legitimacy, ruling has been impossible. This in turn necessitated the calling for an election earlier than the scheduled 2023 poll.

Monsoon polls

Still, there seemed to have been a sense of desperation with the Malaysian government’s speed and sudden urgency with which it dissolved Parliament. And it put the Malaysian Election Commission in a tight spot. If it called for elections early within the 60-day mandatory period, it would be denying the opposition time to campaign. This is also a tactic used by the People’s Action Party in Singapore, hence making it difficult for opposition politicians to gain a foothold in politics.

Yet if the commission called for the election later, Malaysia will head into its monsoon season, which means people are less likely to vote and the number of places where they can cast their ballot will also be drastically reduced, as election avenues such as schools and community centers would be turned into emergency shelters. This would lead to a form of voter suppression.

For now, the election commission has elected to have it on Nov. 19, as close to monsoon season as it possibly could without putting voters in severe danger, while keeping with the democratic requirements of an election. Robertson comments, though, “PM Sabri’s decision to hold elections in November, when parts of Malaysia are regularly hit with heavy rains and floods, is also a big risk. And we will have to watch what happens on election day to see whether these factors limit turnout in some areas.”

Youth vote?

One group being closely watched during Malaysia’s 15th General Elections is the country’s youth. Much has been said about the youth vote in the country. There is a belief that younger people are progressive, and tend to vote democratic and against incumbents. In Malaysia, they are considered a serious voting bloc, “kingmakers” who are a “political game changer.”

It is true that the youth demographic is a growing market, especially after the voting age in Malaysia was lowered to 18. A closer look at the data, however, shows a slightly different picture. There are just three seats dominated by the youth, and they are all in rural Sabah. These votes will tend to be consequential, but, as a voting bloc, not enough to make a change in government. In the urban centers where the youth vote is both plentiful and leans progressive, democratic candidates already have a stronghold; in this case, youth votes won’t make much of a difference either.

There is a new group of young voters who have come of age in time for the 2022 election, which translates into a staggering five million new votes. But the optimism of 2018 seems to have faded, and the current apathy of the youth makes it uncertain as to whether they will even vote, let alone swing the Malaysian government to the left.

Ismail Sabri is pitching himself as the right man to continue in the position of PM. The utter incompetency of the Malaysian government, however, suggests that there needs to be a whole new leadership if the Malaysian state is to have any hopes of moving toward being a true democracy in the 21st century. Whoever comes to power in November this year will have a difficult job. Uncertainty dominates Malaysian politics and old tensions will almost definitely create another stalemate situation.

This new PM might again be just the first of many.◉