|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

B

omb attacks are taking place more frequently across Afghanistan these days, belying the ruling Taliban’s claims upon taking over power more than a year ago that it will provide security to all Afghans. But one ethnic and religious minority group, in particular, is watching such violent incidents with growing concern: the Hazara.

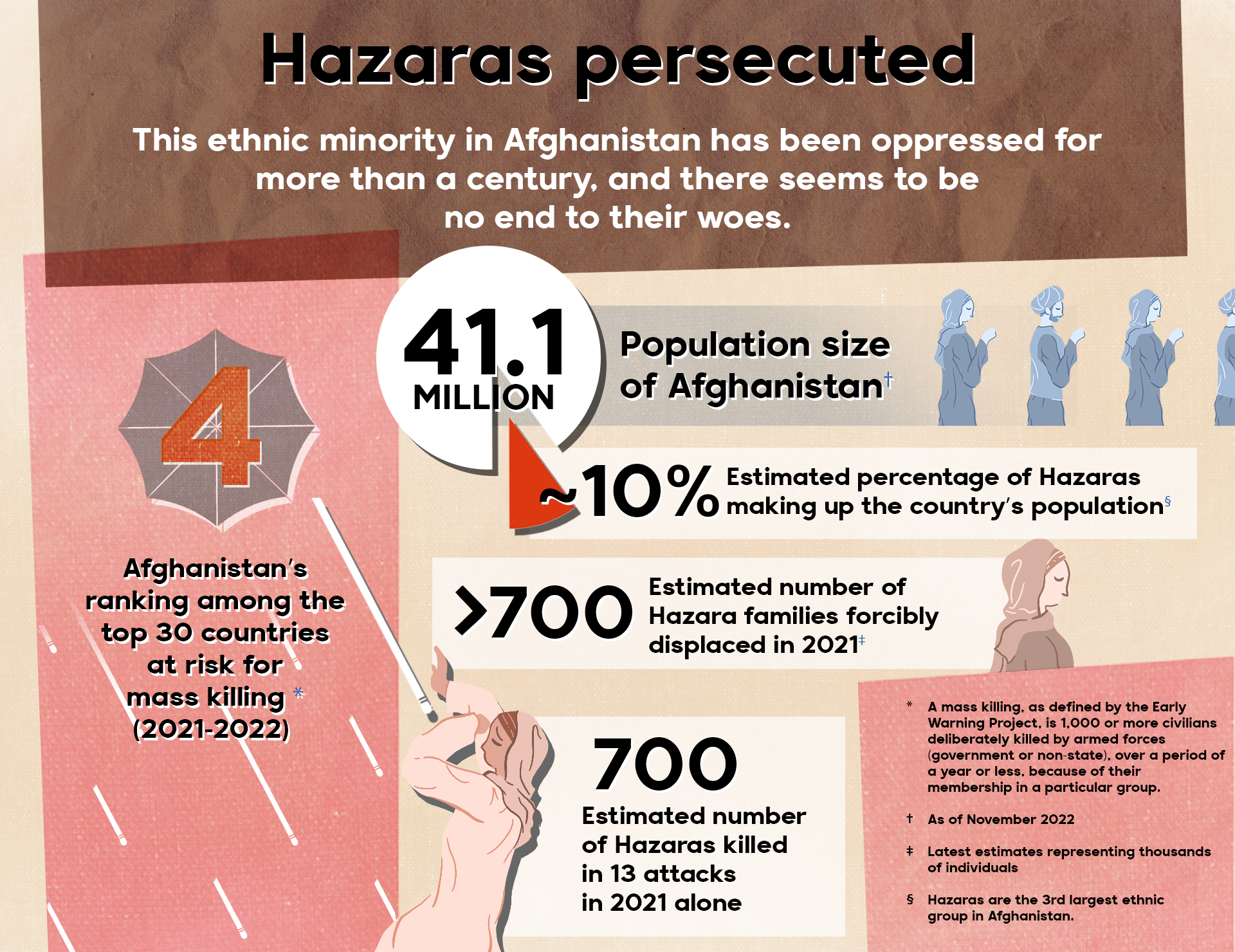

Native to central Afghanistan, Hazaras currently make up at least nine to 10% of the country’s population of nearly 40 million. They are the third largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, following the Pashtun (42%) and Tajik (27%). Other ethnic groups include the Uzbek, Turkmen, and Baluchi.

For generations, the predominantly Shi’a Muslim Hazaras have been among the targets of violent attacks in Afghanistan, where Shiite Islam is practiced by the majority. In 1998, Taliban forces looking to avenge the death of some of their members killed at least 2,000 Hazara civilians in Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan. Even when the country came under U.S. occupation beginning in the early 2000s, Hazaras still suffered discrimination, abuse, and physical attacks.

And so when the Taliban pledged to bring back peace and stability in the country after it took control of the government in mid-August 2021, the Hazaras were wary. Recent events have only confirmed their worst fears.

A recent report by Human Rights Watch said that after “the Taliban took over Afghanistan in August 2021, the Islamic State [ISIL or ISIS] affiliate has claimed responsibility for 13 attacks against Hazaras and has been linked to at least three more, killing and injuring at least 700 people.”

The report added: “The Taliban authorities have done little to protect these communities from suicide bombings and other unlawful attacks or to provide medical care and other assistance to victims and their families.”

However, Abdul Salam Hanafi, the Taliban’s deputy prime minister, has refuted these claims, calling reports of human rights violations in Afghanistan “Facebook rumors.” In a meeting with UN special rapporteur Richard Bennett in October 2022, Hanafi said that the Central Asian country is completely secure and that the “Islamic Emirate is committed to protecting the lives, property, and dignity of all citizens without discrimination.”

Yet just several days before Hanafi met with Bennett, a suicide bomber had blown himself up at a Kabul study hall where hundreds of students were taking a mock test in preparation for university entrance exams.

Targeting the young

The study hall is in Dasht-e-Barchi, in the western part of the city that is inhabited mainly by Hazaras. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan put the number of fatalities in the Sept. 30 bomb blast as more than 50 and the wounded over 100 people — figures that were far more than what the authorities released to the media. Most of those who were killed were young women who were determined to continue with their studies despite the Taliban’s refusal to let girls receive education beyond the sixth grade.

According to survivors of the blast, the suicide bomber began the attack by shooting repeatedly. Then he positioned himself in a classroom of female students before he blew himself up. The study hall had both male and female students.

“I was in class when I heard a loud shooting noise,” recalls 18-year-old Sabera from Daynkundi Province, who sustained injuries from the blast. “I hid under the desk. There was a lot of commotion in the classroom so I couldn’t see who was shooting or where the noise was coming from. I just closed my eyes and ears because I didn’t want to see what was happening.”

Nazneen, also 18, says, “I was in another classroom when the shooting started. Just as our principal ran to close the door, the suicide bomber fired at him. Then he entered the classroom, started shooting at the girls, and then blew himself up.”

“I lost many of my friends that day,” she says.

It wasn’t the first time Dasht-e-Barchi had suffered such an attack. On April 19, 2022, explosions rocked the all-male Abdul Rahim Shahid high school and Mumtaz Education Centre nearby. According to some estimates, more than 100 students were killed.

In an interview with Right Livelihood, an organization promoting sustainability, peace, and justice, former Afghan Women’s Affairs Minister Sima Samar, said of Kaaj Education Centre, the site of the Sept. 30 blast, “This specific center was part of the center which has been attacked twice before. So, it’s not new. And the other problem is that every time before, ISIS, or Daesh, was taking responsibility. This time, nobody took responsibility.”

Sources tapped by a UK parliamentary inquiry on the Afghan Hazaras said that the targeting of young Hazaras aims to “disable and destroy the vital pillar within a community and put the whole group in a resistless and vulnerable position.”

Released in August 2022, the “Hazara Inquiry” report also quoted sources as saying, “(The) intention behind these attacks is not only to kill its youth and disable the future of a community but, by forced displacement, a vulnerable condition is created where the Hazara community will not thrive and prosper in the long term.”

“New patterns of violence”

The bombing at Kaaj Educational Centre sparked some of the biggest protests against Taliban rule. Women took to the streets across the country — in Kabul, Herat, Ghazni, Mazar-i-Sharif, and Bamyan — protesting against the Taliban’s restrictions on their education and its failure to protect minorities.

Aside from bombings, there have been other forms of attack against the Hazara in Taliban-governed Afghanistan, among them land-grabbing. Another source told the UK parliamentary inquiry of “new patterns of violence against the community, including detainment, torture, shooting, summary execution, killing without taking responsibility.”

The report quoted Dr. Gregory Stanton, founding president and chairman of Genocide Watch, who said, “A very slow genocide is occurring against the Hazaras … what we are worried about is that it will eventually ramp up and become a full-scale genocide that we saw in Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998.”

Yet Mohammad Jawad, who lost his 18-year-old daughter Aneesa on that fateful day, confesses that, at first, he had been hopeful about the return to power of the Taliban last year because, he says, the security situation improved significantly.

Jawad no longer thinks that. He says, “My daughter only wanted to study and fulfill her dreams of becoming a doctor. But now she is no more.”

“When I heard a loud blast, I ran outside to ask people what it was,” Jawad recounts. “Soon I learned that it came from where my daughter was studying. My son and I went to hospitals to check for injured patients. But then they showed me a dead body whose face could not be identified. I didn’t believe it to be my daughter and continued looking. But it was Aneesa.”

“I was devastated,” Jawad says. “The situation in Afghanistan is not in anyone’s control anymore.”

A helping hand

However, a more precise description of the situation could be that the Taliban simply does not care what happens to the Hazara, whom it considers infidels and heretics. There is little indication that Taliban authorities have investigated the Sept. 30 blast, and no one has been brought to justice for other similar attacks against Hazaras. Some rights groups even claim that aid meant for Hazara communities usually gets diverted to other people.

Fortunately, though, the families affected by the Kaaj Educational Centre attack have received help from Aseel, a local nongovernmental aid organization. Founded in 2019, Aseel first developed a mobile app to sell local handicrafts to global markets. But after the U.S.-backed government fell and Western sanctions were imposed on Afghanistan under Taliban rule, Aseel used its donor network of Afghan diaspora and non-Afghans to help families in need of emergency relief.

“Transferring money into Afghanistan is a big issue,” explains Ahsan Hassan, who leads the emergency response and funding for Aseel in the country. “But we managed to sign on the vendors, who we pay on a monthly basis. Sometimes we paid them using cryptocurrencies. But now we transfer money from the United States into Dubai and manage funds from there.”

Sabera and her family were among Aseel’s first beneficiaries, receiving cash assistance that is still helping pay for the treatment of her injuries.

“My father is the only earning member (of the family),” says Sabera, who moved to Kabul with her parents so that she and her seven sisters could continue their studies. “The cash we received was helpful. But I always dreamed of supporting my family.”

Even though she still has nightmares from that day, she says that there is no stopping her from completing her education. “I will not quit my studies,” says Sabera. “I will go back to the classroom as soon as I recover. I will study harder than ever.”◉