|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

M

ost of the world has now come out of lockdowns prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, but Iffu is not about to venture out of her home anytime soon. In fact, since she identified herself as transgender five years ago, Iffu has been confined to her house by her own family. She hasn’t been allowed to wear clothes of her choice, spend time with transgender friends, and express her gender. The pressure from her family sometimes leads to verbal abuse and even beatings.

“I am living a solitary life,” says the 20-year-old, who likes being called “Iffu” instead of her given name. A resident of Indian-administered Kashmir, she says, “I sometimes feel I don’t belong to this society.”

In her teenage years, the abuse became so unbearable that Iffu contemplated suicide several times. But in many ways, her story is not rare, lonelier, or more desperate than those of many other transgender people in the valley. Being a hetero-patriarchal society, the Himalayan region has been a difficult place for transgender people who are being abused and stigmatized.

The unending cycle of disparity and inequality has forced members of India’s transgender community to live from hand to mouth. The community sustains itself by relying on a few occupations like matchmaking, dancing, and singing at weddings, as well as working as makeup artists.

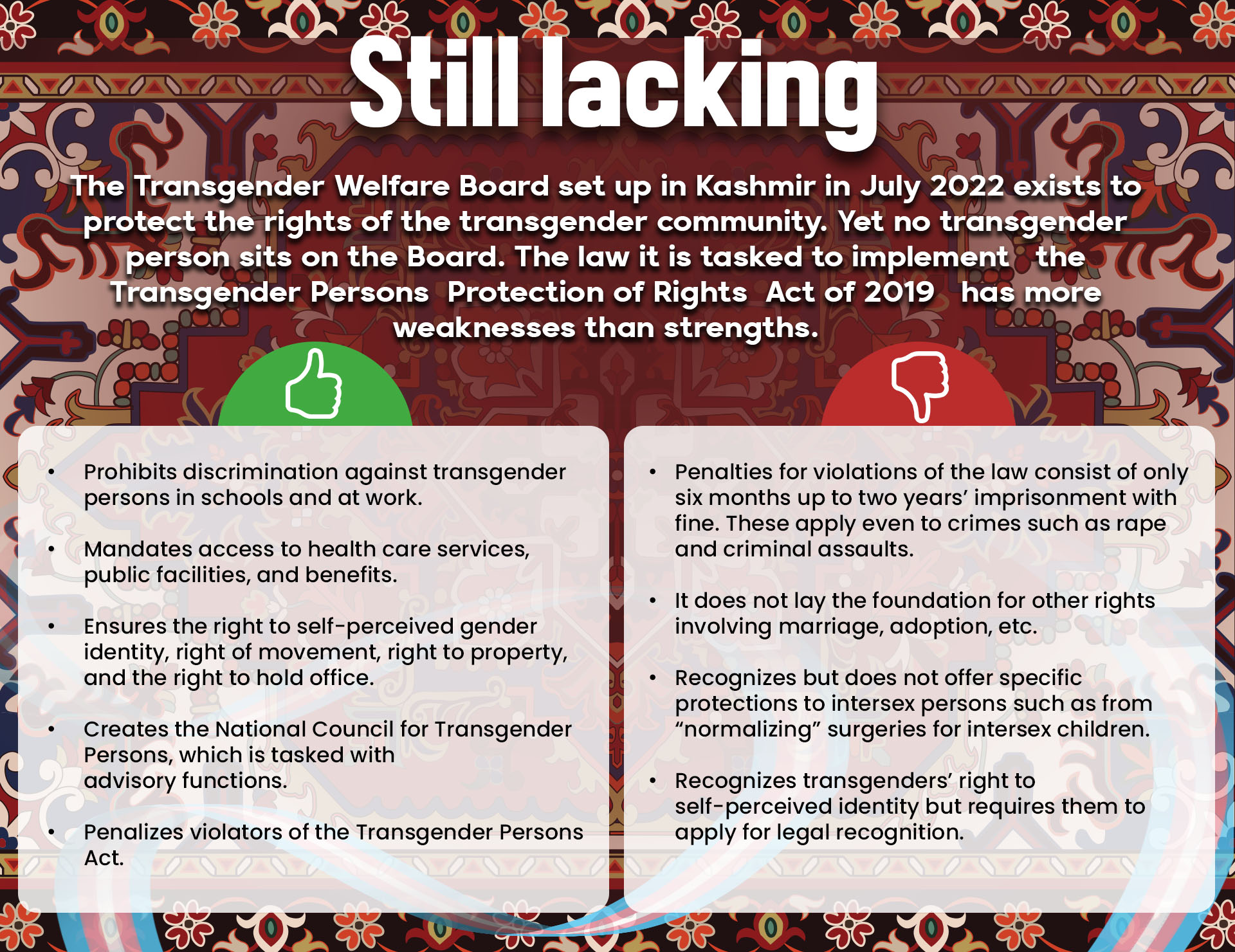

And yet, over the last decade, Indian courts have handed down many landmark decisions that ensure and protect transgender rights. In 2019, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act was also passed. Activists even say that while the implementation of the rules and the law has been far from perfect, trans people in India are arguably in a better place than before.

That is, except for those in places like Kashmir. Here in the northernmost region of the subcontinent, trans people are less visible compared to the rest of India, and there is almost no one fighting legal battles for them in court.

Observers and rights advocates alike believe a lack of awareness among Kashmiris about the court decisions and the law, as well as the government’s lackadaisical approach toward transgender problems, is among the main reasons why the valley’s trans people still suffer abuse and discrimination.

“There might be a lack of awareness that causes trouble for the transgender community in Kashmir,” says Ankan Biswas, India’s first transgender lawyer. “Since the transgender law came into existence in 2019, many cases have been filed in different courts of India, seeking rights of transgender people.”

Based in West Bengal, Biswas has fought many cases for transgender rights. He says that the Supreme Court’s historic decision in 2014 and the enactment of transgender law in 2019 had given hope to this marginalized community. Remarks Biswas: “If the transgender community isn’t receiving support from people in Kashmir, they should make a community and approach the State Legal Service Authority or even the National Legal Service Authority of India (NALSA).”

Based in West Bengal, Biswas has fought many cases for transgender rights. He says that the Supreme Court’s historic decision in 2014 and the enactment of transgender law in 2019 had given hope to this marginalized community. Remarks Biswas: “If the transgender community isn’t receiving support from people in Kashmir, they should make a community and approach the State Legal Service Authority or even the National Legal Service Authority of India (NALSA).”

NALSA provides free legal services to the weaker sections of Indian society. It was NALSA that had filed a petition in Supreme Court, paving the way for the historic 2014 decision that identified transgender as the third gender in India.

Deviyani Chaturvedi, the co-founder of the child and trans-rights-focused Dehat Organization, echoes Biswas. She says, “I can give advice to transgender people in Kashmir to demand the local authority to properly implement the transgender laws in the valley.”

“It is true that transgender cases aren’t being taken seriously either by police or lawyers or any other government officials,” Chaturvedi adds, “but we are fighting tooth and nail for transgender rights.”

Putting rules into practice

On April 14, 2014, India’s Supreme Court handed down its landmark ruling on transgender rights. Besides giving trans people the identity of the third gender, the court extended all fundamental rights to the country’s transgender community. It said that every state and Union Territory must follow the ruling and bring trans people into public spheres and out of marginalization.

In 2018, in response to several Public Interest Litigations (PIL) filed by various groups, the Supreme Court of India struck down Section 377 of the Indian Constitution that criminalized homosexuality. The court said that irrespective of gender and sexual orientation, every individual has a right to live with dignity and autonomy and to make personal and private decisions without state interference.

Then came the transgender bill that was enacted into law in late 2019. Besides prohibiting discrimination against transgender people in education, health, employment, housing, and other spheres of life, the law allows transgender people to have a self-perceived gender identity. By September 2020, the act had implementing rules and regulations so that it could be enforced across India.

Trans rights advocates themselves say that the rules’ implementation has been slow-going, hence the need for cases to be filed in court. In Kashmir, however, there has been little or no movement at all when it comes to transgender rights. Indeed, it seems to boil down to sheer perseverance and a lot of luck for a trans person to live with respect in the valley.

In the case of Reshma, there was a third ingredient for her success: support from relatives who were not necessarily among her immediate family.

“In my teenage days, I was harassed by my family whenever I would express my gender,” she recalls. “Had some of my relatives not supported me, I would have left my family in my youth.”

Like Iffu, the 57-year-old Reshma prefers to go by a name she chose instead of that given by her parents. She says that her story had been much like those of other trans people in Kashmir. It was only much later that she began overcoming the barriers of gender discrimination.

Like many other transwomen in India, Reshma sings and dances at weddings for a living. With the advent of high-speed internet, videos of Reshma’s performances started going viral on social media. She says, “Since people came to know me through my singing, they started respecting me. Everywhere I go people love me and show affection toward me.”

“But,” Reshma admits, “that doesn’t mean transgender people like me have been accepted by society.”

Shreen Hamadani, a scholar working on the representation of the transgender community in local media, says that the extremely hostile and intimidating social settings in Kashmir do not allow transgender people to even speak about their daily problems in public.

“There is so much prejudice against transgender people in our society,” she says. “Even days will be less to explain the harassment and social stigma transgender people have been subjected to in Kashmir.”

Hamadani believes some socially constructed concepts that have become an entrenched part of Kashmiri society play a major role in pushing the transgender community to the margins. Among these are that trans people are immoral and that most faiths have disowned them.

Aijaz Ahmad Bund, another academic and the valley’s only trans rights activist, says, “In Kashmir, almost everyone is of the opinion that transgender people are an abomination. When transgender people are still in the process of identifying their gender, negative messages against them start creeping in.”

A lonely and uphill battle

Bund has been fighting for trans rights in Kashmir since 2011. He authored Hijras of Kashmir — A Marginalized Form of Personhood, the first ethnographic study of trans people in the valley. Released in book form in 2017, the study found that intense harassment has caused mental health issues in trans people, including depression, suicidal tendencies, panic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

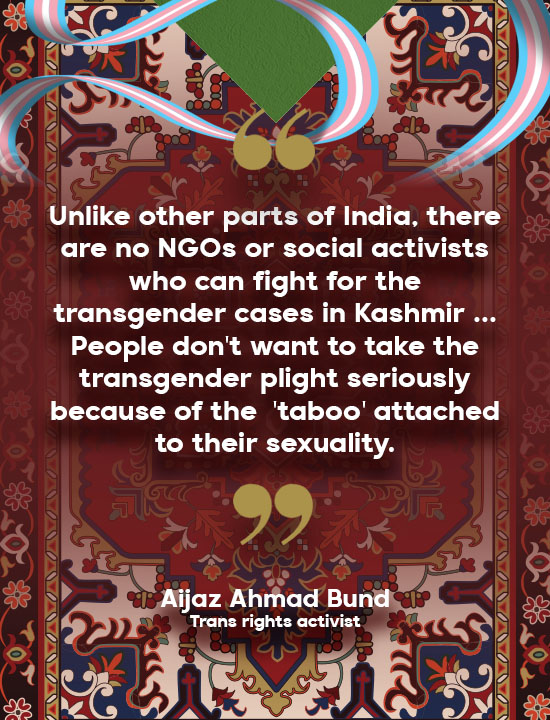

Bund rues the lack of organizations or social activists fighting for transgender rights in Kashmir. He believes this is partly why the Court rulings and the transgender law have not been properly implemented in the valley.

“Unlike other parts of India, there are no NGOs or social activists who can fight for the transgender cases,” Bund tells Asia Democracy Chronicles. “People don’t want to take the transgender plight seriously because of the ‘taboo’ attached to their sexuality.”

Sometime in 2017, Bund filed a PIL, asking the high court to direct the state authority to implement the Supreme Court order in Kashmir. The PIL seeks social, economic, and political inclusion, as well as rehabilitation of the transgender community and recognition of trans people as a marginalized and vulnerable section of society.

“We are still fighting the case, but nothing good has come out yet,” says Bund, who has also run different campaigns and awareness programs about trans people.

Still, in 2017, for the first time in Kashmir, the valley’s assembly discussed the transgender plight. The government then decided to include in the annual budget welfare measures for trans people and categorized them as people below the poverty line. It promised free life and medical insurance as well as a monthly sustenance pension for those aged 60 and above and registered with the Social Welfare Department.

These have yet to happen, though. And even if the program does get going, many trans people may not benefit from it because they lack the required documents.

According to the 2011 census, which remains the country’s most recent, Kashmir had 4,137 trans people, including 487 between 0 and six years. Presumably, that figure has risen since. Yet data from the Department of Social Justice and Welfare show that only 110 people so far have applied for transgender certificates and ID cards. Of this number, 89 have received transgender certificates and cards, while 21 are pending.

In 2020, the administration in Kashmir launched an integrated social security scheme to provide monthly financial assistance to trans people alongside those who have minimal to no income. But Bund says that most transgender people were unable to avail of the scheme.

“The administration had asked the transgender people to submit a certificate as proof of their transgender status,” he says. “Most of them didn’t have it.”

Bund says that education is key to changing the lives of trans people in Kashmir because it would enable them to have better job opportunities. But trans people can barely stay in school because of bullying and abuse.

“I believe only education can bring out the transgender community from this cycle of violence,” Bund repeats, “but the harsh reality is almost every transgender drops out at the school level.”

Iffu has a somewhat different take. She says, “People should educate themselves so that they can understand being transgender is a natural phenomenon that can’t be changed by force. Those who know about transgenderism should sensitize others to be trans-friendly and allow us to live a normal life.”

Says Iffu: “That is all we need.”◉