|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

he seven-year-old girl won’t let go of my hand. She wants me to take her along back to the la-la land that she fancies exists beyond the grim water world around us. She lost two siblings out of three to the floods, but it seems she has forgotten that, or has chosen not to remember, and is now concentrating on dashing back and forth between her mother’s lap and mine.

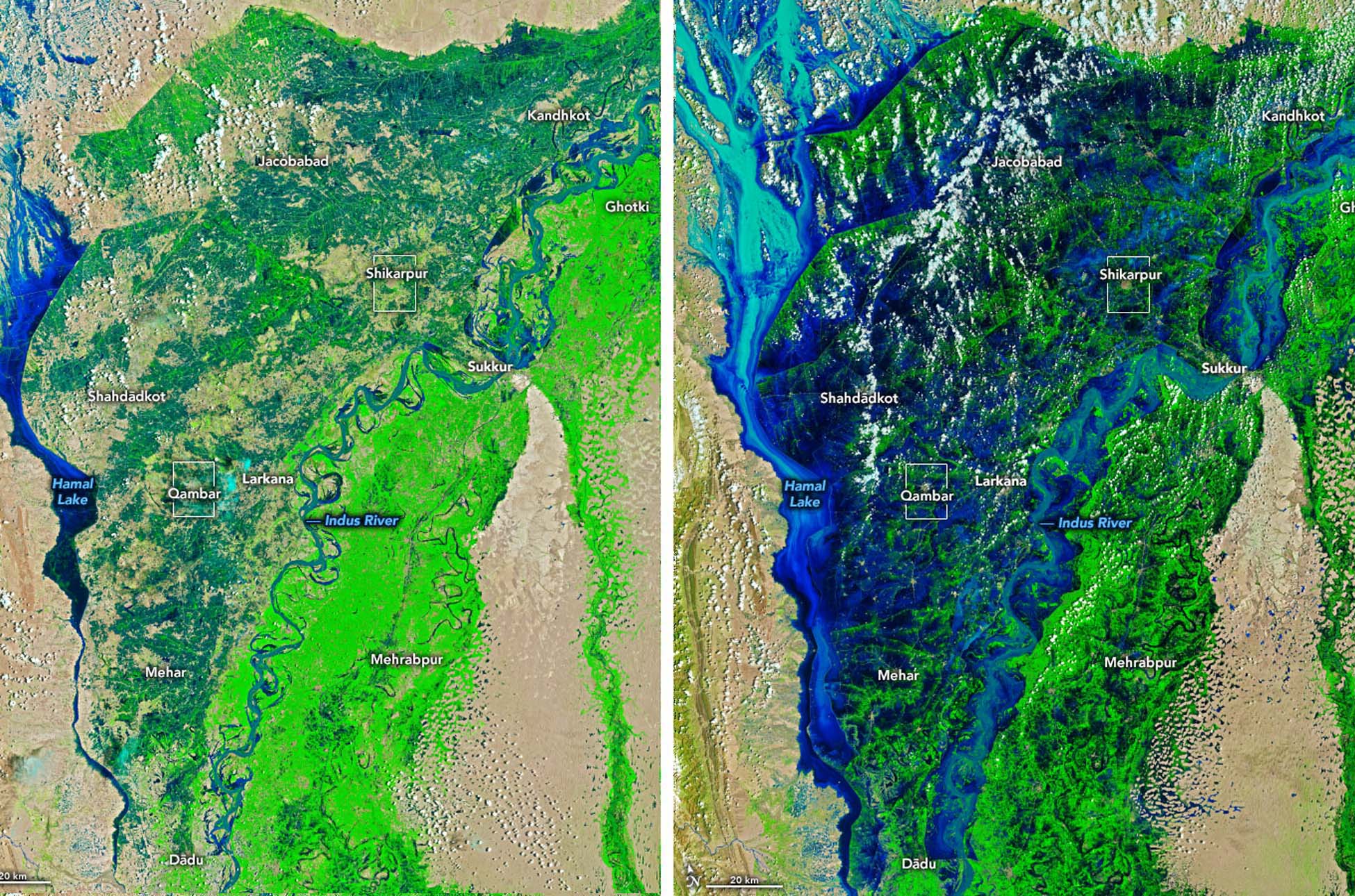

The little girl and her reduced family of four are among the marooned residents of Rojhan Mazari, a town in Rajanpur district in southern Punjab. Like other swathes of areas across Pakistan, the town has remained underwater even months after monsoon rains on steroids that began sometime in June resulted in floods that were more than three meters deep in some places. While the waters have receded somewhat, experts say that much of the floodwaters will still be around for months to come. This means the millions of people trapped by the floodwaters will have to find the will to endure their mounting miseries for a bit more.

In Rojhan Mazari, humans and animals alike shelter on the sides of the Indus Highway, their eyes glued on passing vehicles. Should a car slow down for some reason, every community member, young and old, starts slapping on the windows, seeking water and food, and begging for help of any kind.

This is a scene repeated in many parts of Pakistan, several of which have been cut off from the rest of the country because the floods had washed away roads and bridges and destroyed communication lines. Aid has been slow in coming — if at all — in many areas, leaving people desperate, if not defeated.

“I have no physical energy or will to build my life again,” says 40-year-old Qasim, who lost everything he possessed to the waters that rushed in and rose in Taunsa Sharif, among the worst-hit cities of Punjab. He says: “I don’t even know where to start to gain the strength to rebuild whatever I’ve lost. I wish I was dead, too.”

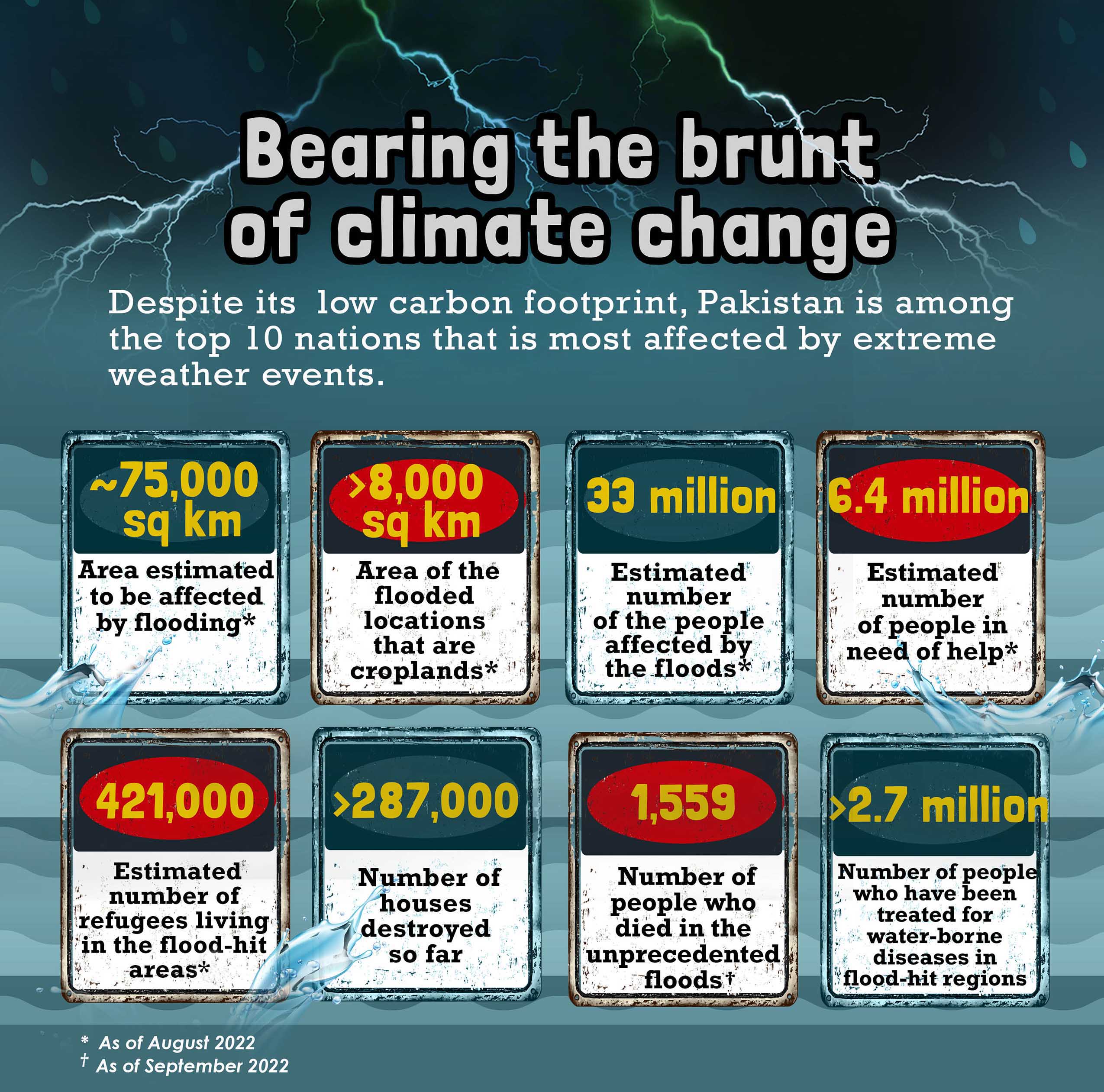

As of the latest count, the floods — the worst in Pakistan’s history yet — have claimed more than 1,500 lives, including those of 552 children, and displaced nearly eight million people. Some 33 million people, or one in seven Pakistanis, have been affected by the calamity. Innumerable buildings have been swept off their foundations, bridges and roads were ruined, and at least 45 percent of the country’s farmland has been destroyed.

Running on empty

For sure, food shortage, lack of shelter, disease, and lost livelihoods in a country where half the population depends on agriculture, selling livestock, or farming, are concerns that top the list of government and non-government rescue and relief efforts. Whenever a mobile truck pulls over in a devastated area, hundreds immediately run toward it; barefoot children carrying babies and younger children rush to join the long queue. But shelters run out of food quickly, and the rations are quickly depleted. While government agencies have set up camps and tent cities with the help of private relief organizations working to help relocate families, authorities admit that relief efforts have been slow. The lack of resources and inaccessibility to flood-ravaged areas are among the most-cited reasons for the delay.

Fast-approaching winter season is a cause for grave concern for those lying stranded under the open sky; those who barely have enough to cover their bodies or burn their furnaces will require warm clothing, bedding, and firewood. Local journalist accounts tell us that an overwhelming number of affected people are angry; they claim that the landlords in their areas are seizing and hoarding whatever flood relief goods they are being provided, a claim denied by the latter.

A boat trip around some areas showed the colossal losses that farmers have incurred. Most have lost a year’s worth of harvest to the deluge, with fields badly swamped and dikes having given in. Fodder for the surviving livestock has dried up or been washed away by the waters. Mud homes have completely sunk underwater, and all that can be seen for miles are treetops or a few isolated rooftops where some people can be seen waving frantically for help.

In the Punjabi town of Isa Khel, where roads have all disappeared and boats are the only way out, a woman’s cries pierce the air; she had lost all her four children to the deluge. In the small city of Dera Ghazi Khan, also in Punjab, a woman tries frantically to take her life by jumping into the rushing floodwaters, while some members of her family struggle to hold her back. Nearby, a jackass overladen with men, women, children, and their meager belongings struggles to wade through murky waters rising up to its chest. But it collapses and sinks before it is hauled afloat by the cart harnessing it.

A man with no money to procure treatment for his 15-year-old son dying from jaundice follows whosoever with folded hands, seeking alms. With most having little or no access to clean drinking water, the flood survivors are forced to drink the fetid floodwater. Over 30 percent of water systems are estimated to have been damaged in the affected areas, increasing disease outbreak manifold. Children and adults are contracting water- and vector-borne diseases, with cases of dengue, malaria, gastrointestinal illnesses, and skin infections rising at an alarming rate.

A pregnant woman who has not eaten for two days is in a state of shock. I am told that she got separated from her family after her mud home was destroyed by the floods. She sits on a boulder by the completely drowned fields, staring into space and not uttering a word or blinking an eye. As we try to give her some water to drink, she starts to scream. Before we know it, there are clicks from mobile phone cameras, making her race away, yelling and howling hysterically.

“Climate carnage”

The psychological toll the disaster and its aftermath have had on people is overwhelming. Fear and anxiety hang thick in the air whenever there are dark, heavy, and gloomy clouds and the skies rumble and roar. Says Umair Latif, a relief worker from a local rescue organization, “The survivors of this grave calamity need to be talked out of hopelessness and built up themselves before they can rebuild theirs and others’ lives.”

But, he admits, “We can’t have therapists or psychiatrists here any time soon, since there are a lot of other goods and medical services that are much above in priority. Mental health needs are not taken very seriously, anyway, even as part of rehab efforts.”

Seeing the devastation up close recently, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres described it as “climate carnage.” He also said that the world owes Pakistan “massive” help in recovering from the catastrophic floods because the developed world is responsible for climate change, which has contributed to the floods. Any assistance from the rich countries is, hence, a reparative measure, not aid.

Indeed, researchers have attributed the disaster to climate change, saying that the intense heatwave that preceded this year’s monsoon season had been a warning of what was about to happen. In a scathing piece in the Guardian titled “Why should we in Pakistan pay for catastrophic floods we had no part in causing?”, Pakistan’s Climate Change Minister Sherry Rehman pointed out, “The G20 alone accounts for 75% of global emissions, many times more than those of the club of climate-vulnerable countries, which includes Pakistan, who emit less than 1% of greenhouse gases but end up paying over the odds in human, social and economic costs for the carbon profligacy of others.”

And yet, this was a disaster that Pakistan saw coming. In May this year, the Pakistan Meteorological Department issued warnings of unusual monsoon rains and flash floods. But while the first deluge of floods started the devastation around mid-June, the formation of a National Flood Response and Coordination Centre was announced only at the end of August.

Many argue that the agency focuses merely on a broad framework, employing general meteorological data, which has limited use in proper flood planning. It also lacks the technical expertise and experience to mitigate acute climate disasters. The National Disaster Management Authority and its provincial counterparts working on the ground meanwhile require the use of more scientific methodologies so that up-to-date weather models can be employed to support effective disaster preparedness and management.

While the G20 countries are responsible for cleaning up the mess they have created, Pakistan has its own house cleaning to do.◉