|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

O

pium has unleashed serious addiction havoc in Afghanistan, which also happens to be the world’s biggest opium producer.

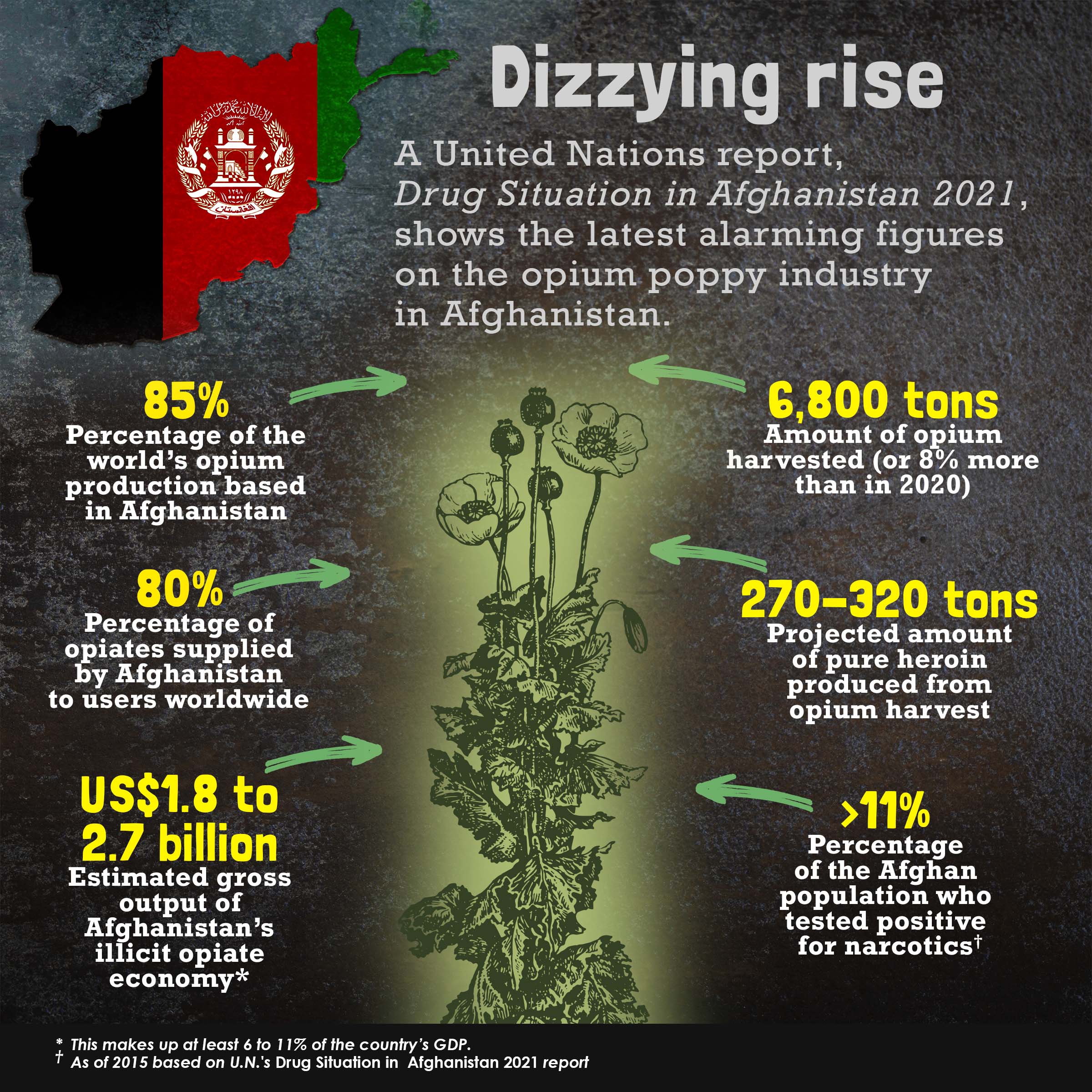

Before the Taliban’s recent ban on growing opium poppy plants, Afghanistan accounted for 85 percent of the world’s opium production and supplied 80 percent of the opiates to users worldwide. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that in 2021, the gross output of Afghanistan’s illicit opiate economy to be at least US$1.8 billion, with the total value of opiates making up a minimum of nine percent of the country’s GDP. Many farmers and day laborers have also been relying on the opium poppy industry for their livelihood, especially after the Taliban takeover last year.

But opiate use has posed a challenge for Afghanistan’s own people as scores of them get addicted, even as drug treatment facilities remain limited amid Western sanctions and suspended funding.

According to the 2015 Afghanistan National Drug Use Survey, more than 11 percent of the country’s population, including women and children, had tested positive for narcotics. Indications are that figure has risen since, particularly after the Taliban took control of the country last year, and the general situation across the country went from bad to worse. In fact, Afghanistan is now estimated to have the highest number of opium addicts in the world.

But Dr. Javid Hajir, spokesperson of the Ministry of Public Health, denies that the number of Afghan addicts has increased. He concedes, though, that the ministry has not conducted any recent survey to confirm figures.

“We have 2.9 million regular addicts — men, women, and children,” says Hajir. “Additionally, about 3.5 million people have been diagnosed with positive addiction in their blood. If we count both sides, we have more than six million addicts.”

This April, the Taliban issued a decree prohibiting the growth of opium poppy, used for the production of drugs like heroin, as well as the use and trading of other narcotics. Aside from getting hooked on heroin, however, an increasing number of Afghans are now using crystal meth, a substance much cheaper and easier to produce.

Homeless Afghans addicted to drugs usually gather under bridges to score a hit. In Kabul, thousands sit huddled together under the Pul-e-Sukhta (Burnt Bridge), infamously known for sheltering drug addicts long before the Taliban returned to power in August 2021.

In their efforts to solve the country’s lingering drug problem, the de facto Taliban authorities have been rounding up addicts and forcing them into rehabilitation centers across the country — causing overcrowding and violence.

Ibn Sina Drug Addiction Treatment Hospital, a 1,000-bed facility, is one of the last remaining facilities in the capital that is struggling to manage the surge in patients with limited resources.

“Before the coming of [the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan], there was a procedure to bring addicts into the facility,” says Dr. Anas Soltani, head of Ibn Sina’s psychological counseling department. “However, the Taliban soldiers have brought up to 4,000 patients till now, which is way above its 1,000-bed capacity.” He notes that while the facility used to treat 10,000 patients in a year, they have already reached this number in the last few months.

Soltani adds, “As the international funding has stopped and the West has frozen our capital assets, we do not have enough budget to implement our treatment plans.” Western governments and international aid agencies suspended funding for Afghanistan after the Taliban took over last year; Afghan assets held overseas worth more than US$9 billion were also frozen.

To date, the international community has yet to recognize the Taliban as the legitimate authority in Afghanistan. This has crippled the Afghan economy and healthcare facilities, including drug rehabilitation centers, are among those now starved for funds.

At rehabilitation centers, patients barely get enough food and medicines and complain about being beaten by the nurses.

Thirty-year-old Murtaza, who got addicted to crystal meth two years ago due to financial woes, is currently undergoing treatment for addiction at Ibn Sina. He says, “The workers behave badly with us. I cannot explain because I fear retribution. They just hit people without any reason. I have been hit many times.”

“The food is also very bad,” Murtaza says. “We only have rice and one piece of bread for dinner.”

Almost all the addicts being treated at Ibn Sina say they are addicted to either heroin or methamphetamine, colloquially known as ice or sheesha. Some of them got addicted while doing hard labor in Iran. Among them is Sadu Khan, 55, who says he has been an addict for more than half of his life.

“I first started using opium in Iran,” says Khan, who came to Ibn Sina voluntarily. Echoing other addicts who say they take drugs to increase their productivity and earn more money for their families, he adds, “I was doing very hard work at the time. When you take opium, you no longer feel tired and are able to work longer.”

Now on his sixteenth day at the center, Khan is having withdrawal symptoms.

“I used to make AFN 100 (US$1.13) from pushing a cart,” he says. “But I would spend all of that to buy heroin. Once that money was gone, I worked more to make money for my family. I was working for 19 to 20 hours a day.”

There are also patients who were brought in for treatment by their families. One such patient recently had a visit from his mother, who came all the way from Laghman province, some 153 km of road travel east of Kabul.

“Our family and friends taunt us that our son is addicted,” says the 30-year-old patient’s mother. “We face so much humiliation. I have lost my mind because of him and had a heart attack three times. I brought him here so that he can be healthy again for his daughters.”

But Dr. Hajir says that weaning addicts off drugs at treatment centers is not the only solution to the country’s drug problem. He says that it would take coordinated efforts of three ministries to achieve any significant result.

“To reduce the problem of addicts, the Ministry of Interior must first eliminate the cultivation of opium, Ministry of Labor should provide job opportunities to people, and if all else fails, then they must come to the Ministry of Public Health for treatment or de-addiction,” says Hajir.

Ibn Sina’s Soltani, meanwhile, says that a ban on opium alone is insufficient. He says, “There are enough people addicted in this country. To decrease their numbers will take resources and consistent efforts.” ●

Kanika Gupta is a journalist based in New Delhi, India, and works out of Kashmir and Afghanistan. She reports on human rights from conflict regions.