|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Economist Anushka Wijesinha has one simple piece of advice for countries looking at Sri Lanka right now and praying they don’t end up like it: Don’t act juvenile with your borrowings.

According to Wijesinha, who has worked in both the public and private sectors, Sri Lanka’s current financial woes can be traced to poor money management. “It is not the borrowings that ruined Sri Lanka. It is what we did with the loans that ruined us,” Wijesinha says. “We started doing adult things while having reckless teenage behavior.”

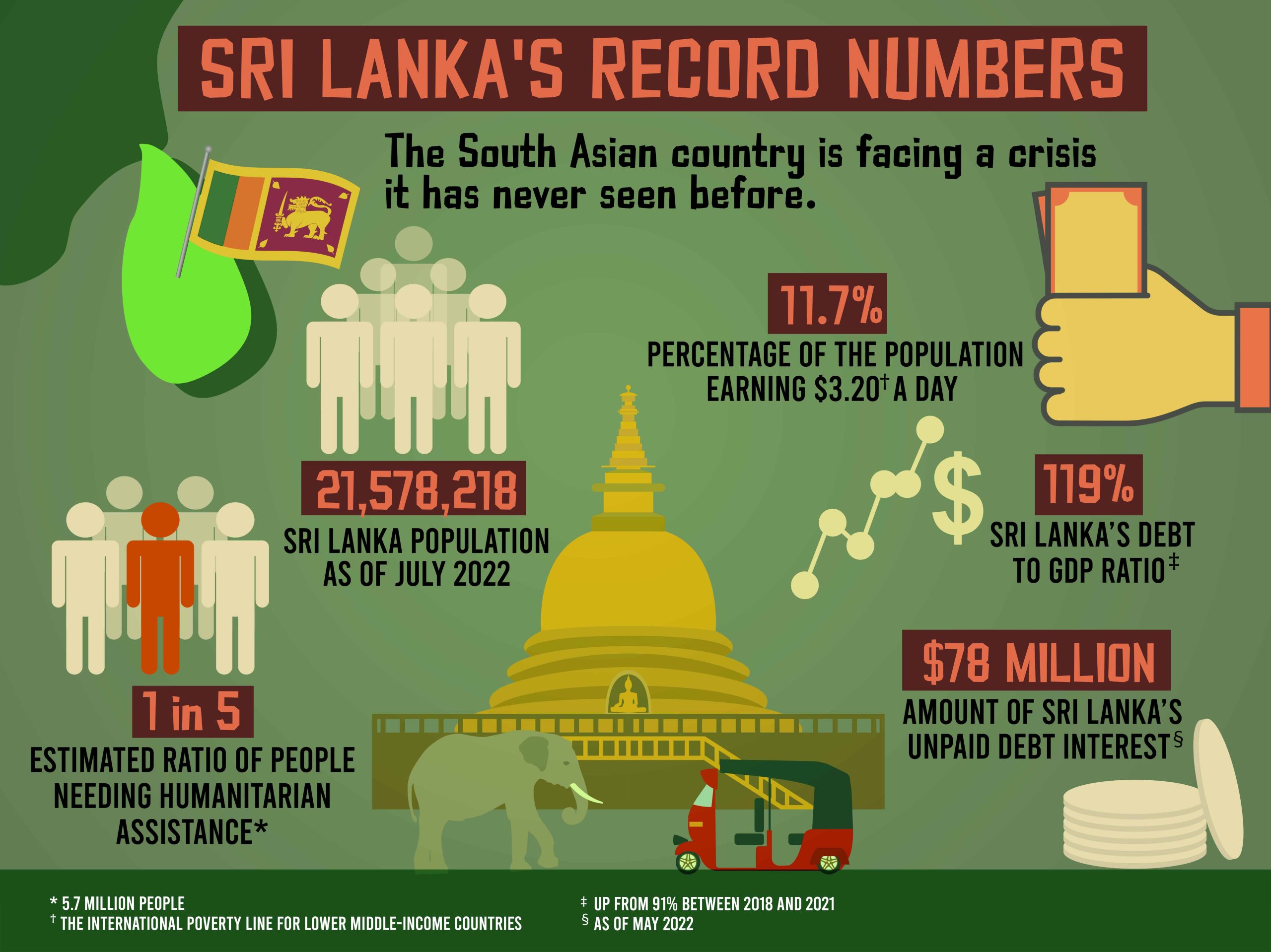

In May this year, Sri Lanka defaulted on a debt repayment of US$78 million. Soon after, the Central Bank indicated that the country had run out of foreign currency to pay its loans. “Until there is debt restructure, we cannot repay,” said Central Bank Governor Nandalal Weerasinghe.

Sri Lankans queue for hours under the hot sun to have their LPG tanks refilled. The situation is the same at petrol stations nationwide, where newspapers have reported at least three deaths due to the heat.

Sri Lanka is currently seeking to restructure around US$50 billion in loan debt. China holds about 10 percent of those loans behind Japan and the Asian Development Bank. China, however, has financed projects that others have stayed away from due to the high risk involved with these.

For several months now, Sri Lanka’s economy has been on a downward spiral, and that trend is unlikely to go in reverse anytime soon. In fact, while Sri Lankans — who have been putting up with gas shortages and soaring food prices, among other things — recently managed to push their leaders out of power, they will not be seeing any immediate economic relief.

A sharp increase in inflation beginning in January 2022 has significantly reduced household purchasing power for food, fuel, and services. According to Sri Lanka’s Central Bank, underlying the 54.6 percent increase in headline inflation in Sri Lanka in June 2022 is an 80.1 percent increase in food inflation and a 128 percent increase in transportation prices.

Sources: Sri Lanka Central Bank, Trading Economics

This, after all, is a problem that began decades ago. It was exacerbated by decisions taken later by the administration of recently exiled and newly resigned President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

In 2009, as a 30-year-old bloody civil war also came to an end in the South Asian island nation, Sri Lanka was elevated to a middle-income country. The flip side of this “promotion” was that international borrowings now had to be negotiated under commercial rates and terms instead of Sri Lanka being able to enjoy concessionary agreements.

The end of the war also affected Sri Lanka’s ability to attract concessionary funding. The United States and European nations leveled charges that government forces had committed serious human rights violations and were pressing for wider international scrutiny of the then Mahinda Rajapaksa government. The latter was able to stave off such an inquiry with the help of Russia and China. Constant Western pressure, however, meant its borrowing options were severely limited.

Debts and tax cuts

But that did not stop the Mahinda Rajapaksa government from going on a borrowing spree to fund its megaprojects and tapping one of its “defenders” — China — for several loans in the process. The billions of dollars in loans did not go into astute investments, though. Points out Wijesinha: “One thing that regional nations can take a lesson from the Sri Lanka situation is not to take on debt that you do not invest wisely.”

For example, while Sri Lanka now has thousands of kilometers of highway, many of these do not provide links to or are catalysts for industrial zones. Economists say as well that commission-taking and bribery became rife in such highway projects.

Sri Lanka also built a US$1-billion port that it has since leased to China Merchants Port Holdings Company to manage losses that were estimated to have reached around US$300 million before the Chinese firm took over. Then there is the US$200-million airport that has been mostly empty and has become a financial bleeder. For a while, it was used as a massive storage unit for paddy. Former aviation minister Nimal Siripala de Silva estimated that the airport could be draining the economy of as much as US$500,000 every year.

While borrowing heavily for projects that would later turn out to be non-performing, Sri Lankan governments from 2009 onward also spent lavishly on public subsidies and handouts. At the same time, they granted generous tax cuts. In 2019, in keeping with election promises, then newly elected President Gotabaya Rajapaksa initiated sweeping tax cuts, including the reduction of the value-added tax rate from 15 percent to eight percent.

Sri Lanka’s dollar reserves have been declining since the end of 2019, following the re-election of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. By November 2021, the country’s dollar supply had fallen to a 13-year low. With food and gasoline import expenses expected to rise by the beginning of 2022, the Central Bank devalued the rupee in March. The domestic currency has since lost more than half of its value against the dollar.

Sources: Sri Lanka Central Bank, World Bank, Knoema

Ali Sabry, who was finance minister for a brief period in April, told parliament in May that in the ensuing two years, tax revenues had halved. Sabry also called the tax cuts a “historic mistake,” with the reduction in government revenues being felt even more as the pandemic wore on. Indeed, with fewer tax revenues and the pandemic putting a squeeze on the previously high-earning tourist sector and remittances from Sri Lankans working overseas, the government became more and more cash-strapped. It then began to pay old debts with new borrowings, as well as embarked on desperate measures to save what little foreign currency reserves it had left. Among these was an ill-advised order to stop fertilizer imports, which triggered a food crisis.

Today Sri Lanka’s situation is dire, unlike ever before. This month the United Nations assessed that one in every five Sri Lankans is in need of humanitarian assistance. There was never poverty at these levels even at the height of the country’s three-decade war.

Fueling protests

The World Food Programme has called Sri Lanka a “bellwether” for other countries. It says that 85 percent out of a population of 22 million have been affected by the crisis, but in reality, no one has been spared. The impact of the country’s economic turmoil on its people has been harsh and is spread across the entire island.

A few days before hordes of angry protesters stormed the official residences of the president and the prime minister in early July, Nimesh Dias was stuck with tens of other Sri Lankans in one of the now-ubiquitous lines at petrol stations. Said Dias: “It is normal now, waiting for over 15 hours for a tank of fuel, daily power cuts, rising prices, lack of medicine, people protesting, and elected officials oblivious to all that.”

Some have actually waited in fuel queues for as long as 10 days without getting anywhere near the pump. As Dias and the others stood there in the unrelenting Sri Lankan summer heat, a distressing video began to circulate on social media: A son had discovered the lifeless body of his father who had been waiting in a fuel line.

The papers would later report on at least three deaths linked to queuing for fuel. By the week that President Gotabaya and his family fled Sri Lanka, at least 14 deaths had been reported either at fuel queues or related to them.

To date, the Treasury still does not have enough foreign currency for fuel imports; the release of foreign currency for each shipment of fuel or gas now makes national news in Sri Lanka. The country’s desperation for fuel has been such that in mid-June, the government even seriously considered imposing a nationwide lockdown to stem demand for it. Authorities later urged people to work from home and shut down schools instead.

Economist Wijesinha takes the foreign currency crunch as an example of poor planning and lack of financial maturity. He says that instead of assessing the unprecedented financial pressure on the country because of the pandemic, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government carried on like most other administrations before it, assuming that fresh loans could stave off a freefall. It failed to note that when pandemic-related foreign exchange pressures hit in mid to late-2020, the country was just starting to recover from the 2019 Easter Sunday Bombings that had severely hit the tourism sector.

Sri Lanka’s foreign debt has been steadily increasing since 2005, but it has already overtaken its GDP. Furthermore, as commercial borrowings have increased in recent years, the maturity of its debts has become more short-term and less flexible, tightening the squeeze on consumers.

Sources: Sri Lanka Central Bank, World Bank

“Sri Lanka worked on the attitude that it was okay as long as it could keep borrowing,” says Wijesinha. “The government had decided that they could manage the situation and not seek help. It was spending precious foreign reserves to pay loan installments.”

Yet even as Sri Lanka was unable to borrow as much as it did before the pandemic took hold, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government actively resisted seeking bail-out options that would have meant spending cuts.

Sri Lanka is currently in negotiations for a financial redress package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). But Wijesinha says that Sri Lanka should have sought that help much earlier.

Realistically, he also says, funds from the IMF are unlikely to start flowing in Sri Lanka’s direction until the end of 2022, at the earliest. “Sri Lanka has to not only come to an agreement with the IMF on macroeconomic adjustment measures and debt sustainability but also negotiate with creditors on debt restructuring,” he says. “And this is the process that is likely to take time.”

It cost Sri Lanka US$104.3 million to build the 350-meter tall Lotus Tower in the background, with 80% funded by China. After the tower opened to the public in 2019, it failed to generate significant revenue, becoming yet another white elephant for the country.

Meanwhile, things will probably get worse before they get better. Observed the United Nations in a detailed report on Sri Lanka’s food crisis: “Prices of most commodities have increased considerably since the end of 2021, with food prices as measured by the Colombo Consumer Price Index increasing 57.4 percent over the year to May 2022, up from 10 percent for the equivalent period in September 2021. As a result, families have started to resort to eating less preferred or less expensive foods daily and limiting the portion sizes of meals.”

Political uncertainty will foreshadow any austerity measures. As this article is being written, President Rajakapsa finally sent in his letter of resignation from Singapore, where he fled after landing first in the Maldives. Sri Lanka is still under a state of emergency, which was declared by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe as acting president. Parts of the country have also been placed under curfew. Protesters, however, want Wickremasinghe to resign as well. ●

Amantha Perera is a Sri Lankan Ph.D. researcher at the School of Education and the Arts of the Central Queensland University, Australia.