|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

When a second wave of COVID-19 hit India in the summer of 2021, tens of thousands of people across the country scrambled to secure oxygen tanks, medicines, and ultimately, beds in hospitals. At Anganwa Camp, a settlement of Pakistani Hindu refugees in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, residents were scrambling as well. Then again, they did that every day, and for more basic things.

The camp in the Thar Desert had no piped drinking water, few common toilets, and no solid waste management. The small shanties, all built of locally available mud, stone, and thatch, were like furnaces during the day, compounded by the open-hearth stoves.

“Many people fell ill with dengue fever, diarrhea, and malaria,” recalls camp resident Ram Chandra Solanki. “My sons would get up at four a.m. every day to trudge one kilometer away to fetch drinking water.”

Solanki says that in their makeshift camp, summer heat and its attendant woes eclipsed their fear of COVID. “We had little access to government health facilities — there are about 1,200 people in the camp, and half of us don’t have any ID proof [which is needed for treatment there],” he says. “Many people simply endured fever, cough, and other COVID-like symptoms without getting tested or treated.”

The temporary nature of the camps also means the refugees live in makeshift dwellings, though many stay for much longer than expected. Rohingyas in this camp in Haryana make do with plastic sheets as walls to protect their shanties from rain, but the shanties lack ventilation during the hot, summer months. (Photo by Geetanjali Krishna)

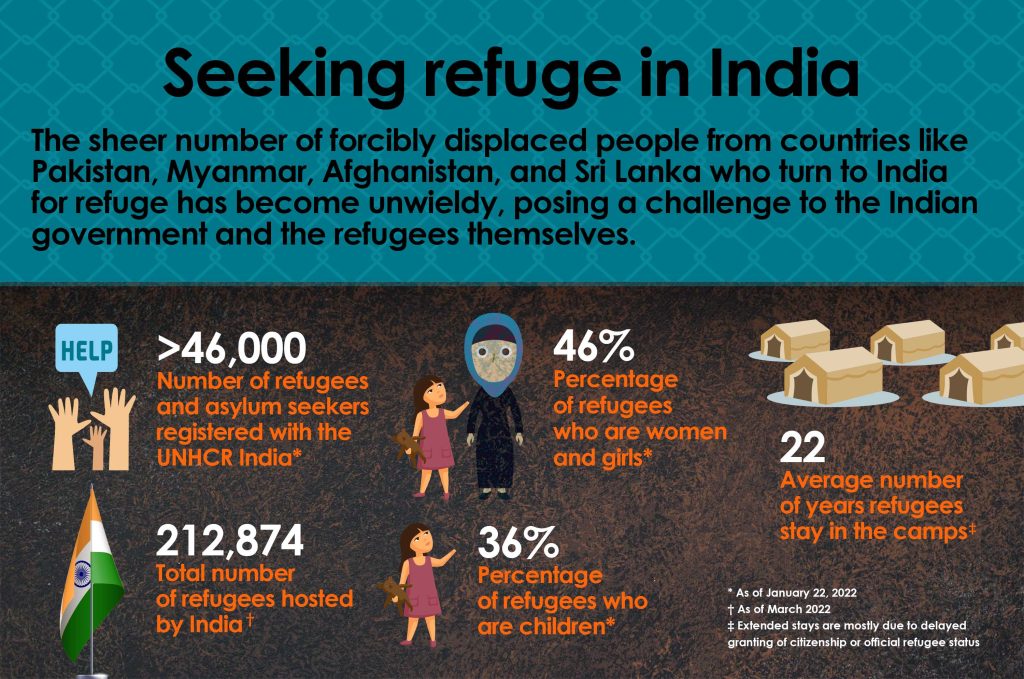

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that there were 89.3 million forcibly displaced people worldwide at the end of 2021. By May 2022, that number had climbed to more than 100 million. UNHCR says that of the 2021 total, 83 percent were being hosted in low- and middle-income countries like India.

Host governments house refugees in temporary camps, where state-supplied health care, water, sewage systems, electricity, and other services are hard to access. Moreover, because the refugees are meant to be in the camps for only a short time, their shelters are not built with the sturdiest of materials or designed for all kinds of weather and are cramped spaces that heat up quickly in the summertime.

India has long been known to be among the countries worldwide that have the hottest of summers. However, in the past years, summer temperatures in the South Asian nation have reached record highs. Extreme heat can worsen chronic illnesses, as well as lead to heatstroke, hyperthermia, kidney dysfunction, and even death.

Mohd Alishaan, a resident in the Rohingya refugee camp in Haryana in northern India, says that in their crowded shanties, hearth stoves are often too close to the bamboo walls, increasing the risk of fire and heat stress. The indoor air pollution caused by the stoves makes the refugees vulnerable as well to pneumonia and other acute respiratory infections.

An infrastructure crisis

“Most of the common health problems faced [by refugees] are due to lack of infrastructure,” notes Fateh Singh Sodha, a doctor who runs a private clinic in Jodhpur while also treating Pakistani Hindu refugees through Universal Just Action Society, a local NGO. For one, the lack of toilets forces the refugees to relieve themselves in the most unsanitary conditions, which in turn leads to the contamination of the soil and groundwater. Adds Sodha: “Water is not easily available and what they end up drinking is often stored in unhygienic containers.”

A Pakistani Hindu migrant himself, Sodha is especially concerned about the extent of overcrowding in camps. He points out, “Each household has at least eight to 10 members sharing a small space, so if one member contracts an infectious disease, there is a higher chance of other household members falling sick. And when they go to the city to work in factories, construction sites, and local homes, they carry diseases without even realizing it.”

Remarks Rohingya refugee Alishaan: “In the last two years, we have found that it has been impossible for people with COVID, or COVID-like symptoms, to isolate.”

But aside from raising the risks of spreading infectious illnesses, the crowded conditions in the camps also raise indoor temperatures, making summer nights even hotter. Occupational and environmental health expert Vidhya Venugopal says, “Cool nights allow the body to recover from heat exposure experienced during the day. But when the indoor temperature is high, there is no respite from heat stress.”

Most Pakistani Hindu and Rohingya refugees in India work as daily wage agricultural or construction workers. Consequently, during summer, they spend their days working under the burning sun and go home to dwellings that are hot and stuffy.

The living conditions suffered by many refugees are also experienced by those living in urban slums. Yet while local slum dwellers often have no choice but to stay where they are, refugees are even more marginalized, with few rights and limited mobility for as long as they do not have proper papers.

UNHCR estimates the average refugee camp is inhabited for 22 years. The time taken to issue citizenship or refugee papers is a contributing factor to the length of stay in camps. It took Dr. Sodha 11 years to get Indian citizenship. Mohamed Shafique, a Rohingya daily wage construction worker in Mewat, Haryana, fled to India in 2009, but he received a refugee card from UNHCR only in 2015. After he got his papers, he found it hard to leave the camp as it had become home.

Although India is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, it hosts nearly 213,000 refugees and asylum-seekers, mainly from Pakistan, Myanmar, and Afghanistan. Of this number, only 21 percent are registered with UNHCR.

A walk through any of the narrow lanes of Chandeni Camp in Haryana enables one to see how severe the infrastructure crisis gripping the refugee community is. The camp has 157 Rohingya (41 households), living on roughly less than half a hectare of land. The small, bamboo-framed houses have one or two rooms each and are merely 4.6 by 9.1 meters in size. There is stagnant wastewater everywhere in the absence of sewage connections, while plastic sheets on the walls for waterproofing make these homes poorly insulated and ventilated.

Rethinking requirements

At the very least, the dual exigencies of rising temperatures and COVID-19 are now making relief agencies rethink the minimum standard requirements of relief and refugee camps. UNHCR stipulates that “emergency” refugee camps should provide a minimum of 3.5 square meters per person. SEEDS India, a disaster relief and mitigation agency that has been focusing on heat waves in the last few years, is lobbying to reduce camp density standards to five square meters per person.

Sources: UNHCR: India, Protracted refugee situations, OCHA

One bit of good news is that Better Shelter, a Swedish social enterprise that develops and provides innovative housing solutions for displaced persons, has come up with a modular shelter called Structure with UNHCR and the Ikea Foundation. Structure allows a simple metal frame to be insulated with local materials such as tarpaulin, bamboo, or other locally available grasses.

This makes the dwelling better suited to the local environment, ventilated and therefore adaptable to heat, and longer-lasting. Better Shelter has also partnered with SEEDS to set up such modular shelters in India to be used as COVID-19 care facilities.

Nuanced heatwave action plans could also be helpful. Abhiyant Tiwari, an expert in heat health warning systems in India, helped design South Asia’s first heatwave action plan in Ahmedabad, Gujarat after the heatwave of 2010, which reported an estimated increase of 43.1 percent in all-cause mortality. The plan included impact mitigation through early-warning systems, creating awareness about the health impact of heat through mass and social media, and building the capacity of the health infrastructure to deal with a sudden influx of heat-related disorders. An assessment found that in the following years, the heat action plan was associated with decreased summertime all-cause mortality rates, with the largest declines occurring at the highest temperatures.

“Now,” says Tiwari, “we have incorporated a fourth component into our action plans, which is promoting adaptive measures, and preventing exposure.”

A cool roof is one such measure. Under their ongoing Operation Chhaya (Operation Shade) SEEDS co-founder Anshu Sharma and his colleagues have been painting North Indian roofs with white lime and gum, a low-cost, low-tech solution that can lower temperatures by five to six degrees inside buildings.

However, a cool roof is not enough. Sharma says. “Shelters will need green walls (walls covered in creepers to protect them from the direct heat of the sun), improved vegetation, and many other such features to ensure better indoor temperatures during summer. Indoor heat impacts the most vulnerable who stay indoors — elderly, children under five, and women exposed to further heat from cooking, often on open-hearth stoves.”

The lack of proper toilets forces refugees to relieve themselves in unsanitary conditions, such as in this makeshift toilet in the Aanganwa camp in Jodhpur (left). The absence of sewage connections results in stagnant wastewater pooling (right) such as in this Rohingya camp in Haryana. (Photos by Geetanjali Krishna)

“In the long term,” Sharma says, “we have to make our temporary settlements as well as cities more heat-resilient.”

Tiwari echoes this and says that “extreme heat and heat waves are going to be more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting in the near future.” He says, “The heat we’re witnessing today in India, Pakistan, Europe, and America is when there’s been a 1.1 percent increase in global temperatures. This is only going to increase as global warming increases.”

Many heatwave action plans already focus on maximum temperatures. Tiwari believes that going forward, minimum temperatures should also be taken into account. There is no question, though, that investing in heat-resilient infrastructure — not just for refugee camps but across the globe — will be a crucial determinant of public health and well-being in the years ahead. ●

Geetanjali Krishna is the co-founder of The India Story Agency, which specializes in telling environmental, public health, and social affairs stories from South Asia to the world. One of the 16 awardees of the Global Health Security Grant 2021 by the European Journalism Centre, her recent by-lines can be found in Times, The British Medical Journal, BBC Future, The Third Pole, and Business Standard.

Fieldwork for this report was funded by the European Journalism Centre, through the Global Health Security Call 2022. This program is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.