Hong Kong’s supermarkets are famous for having a wide variety of goods in supply. Lately, though, they have been hardpressed to keep a large inventory as increasingly anxious residents crowd the stores and empty the shelves.

Such frequent panic-buying is being triggered primarily by the outbreak of the city’s fifth wave of COVID-19. Indeed, with Hong Kong seeing a record daily surge of infections since mid-February — more than 27,700 new cases on March 15 alone — residents have been in fear of a total lockdown similar to that being carried out in mainland China, and so many have been trying to stock up on supplies.

The problem is that no one has really been telling them any different, and conflicting pronouncements from Hong Kong officials have only made Hong Kongers more jittery and prone to believing the next-door neighbor or chatter on the street. In fact, with most of Hong Kong’s independent media outlets now shuttered, many of the city’s residents are relying more on rumor mills for the latest information about the latest outbreak and other matters.

Hong Kong residents lining up at a testing center in February 2022. As COVID-19 cases rise, many citizens are not aware of how dire the real situation is.

One resident who would like to be known only as Amy for this report says that she has avoided watching the news from local media outlets as she believes their reports are neither critical nor dare to speak the truth.

“Apple Daily and Stand News announced their closures because of the National Security Law,” she explains. “For me, this is like punishing whoever dares to tell the truth. In such a case, what is the point of watching news reported by the media outlets that have survived these days?”

Amy says that she used to count on Hong Kong’s pro-democracy media outlets such as Apple Daily newspaper and online publication Stand News to keep her updated. She says that during the 2019 pro-democracy protests that rocked the city, she was “obsessively reading news.” Says Amy, “I was eager to know what’s happening in our city at every single moment.”

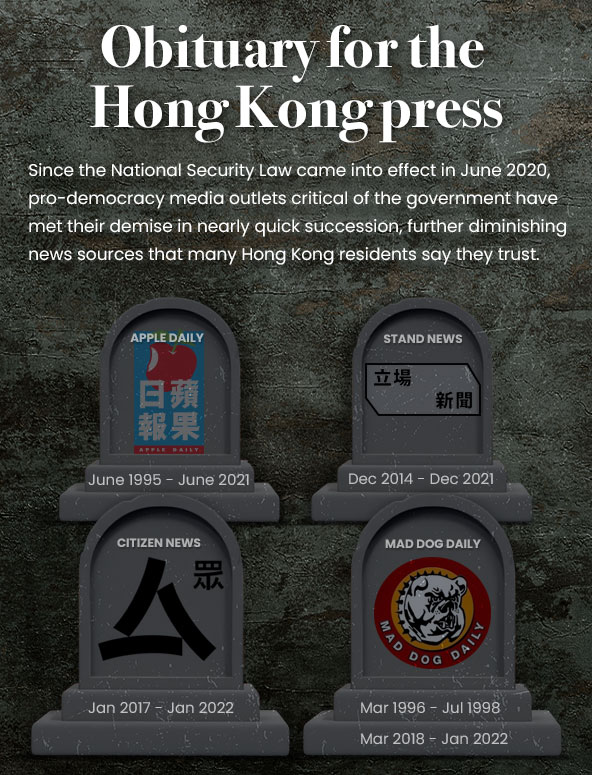

The turning point came in June 2020, when the National Security Law was imposed on Hong Kong by Beijing. In general, the law seeks to suppress challenges to state authority. Hong Kong officials claimed that “Hong Kong’s media landscape is as vibrant as ever” despite the law, but in the past year, three of the most prominent pro-democracy media outlets have been shuttered one after another.

Apple Daily and Stand News were investigated by national security police. Apple Daily shut down in June 2021, and Stand News followed suit six months after. Just this January, online media Citizen News announced its decision to stop operations as a precaution, citing what had happened to Stand News in particular. A month after, the fifth COVID-19 wave began in Hong Kong. According to a March 14 Reuters report, Hong Kong has so far had more than 700,000 coronavirus infections and some 4,200 deaths, “most of them in the last three weeks.” Hong Kong has a population of 7.48 million.

Missing information

There are a few more independent media outlets left in Hong Kong, but none operate on a scale as large as the three that shut down. One of those still standing, Hong Kong Free Press, is in English and is not very popular among the locals. The oldest, InMedia, is in Chinese, but it relies mostly on citizen journalists and therefore lacks the gravitas of the three media outlets that were shut down.

Amy says that as the COVID-19 surge worsens she has tried to remain calm and checks on the official government news site “news.gov.hk” for the latest announcements. But the absence of critiques and discussions of government moves is being felt by residents who want to know more about what is happening.

Former Citizen News editor Cheung Lai San, who has worked in the local news industry for more than two decades, suggests that with mainstream media not breaking out of the government’s news agenda, Hong Kong residents are not getting a real sense of the outbreak and its consequences.

She recalls that earlier in February, Hong Kong hospitals were inundated with COVID-19 patients who tested positive for the coronavirus. Shocking images show hundreds of patients lying on hospital beds just outside a public hospital’s emergency room, as indoor bed spaces filled up.

“Under such circumstances, we (Citizen News) would probably send a reporter to do a live broadcast outside the hospital for at least half an hour, to show how crowded the hospital is and to give the audience a sense of ‘live-ness,’” says Cheung.

If there had been more live broadcasts, she argues, more people might have realized earlier how catastrophic the situation is. Hence, medical resources could be better allocated as probably fewer patients with mild symptoms would rush to emergency rooms.

Cheung says that mainstream media outlets rarely adopt such a reporting approach. A public hospital nurse, who wants to be known only as Victor, agrees with her. He says, “From what I observed, official announcements did not mention how overwhelmed the public hospitals have been until the cat was already out of the bag.”

The nurse also worries over the Hong Kong government’s insistence on the “dynamic zero infection” policy even as public treatment facilities reach capacity. “It’s almost impossible to treat mild and severe cases at the same time,” Victor says while noting that these concerns are not being conveyed to the general public.

He says, “After the recent closure of media outlets in Hong Kong, we have fewer platforms to let the outsiders know what’s going on.”

Faster, bolder

Cheung says outfits such as Citizen News would have had updates regarding government’s practices faster and more frequently than the mainstream media, and with bolder criticism. That would have been helpful in making the public and the authorities alike see the bigger picture, as well as in clearing up things like the recent confusion about a possible lockdown, which was made worse by conflicting statements by officials.

On February 12, Hong Kong Chief Secretary John Lee Ka-chiu and a delegation of Hong Kong ministers had a meeting with mainland Chinese officials in Shenzhen to discuss how to tackle the growing health crisis. But before the results of the talks could be announced, a poll in local forum Lihkg asked users if they thought Hong Kong would impose a citywide lockdown. Over 90 percent of the 3,400 respondents said yes.

Later that night, Lee made it clear that Hong Kong would not impose a citywide lockdown. Instead, he said, it would set up joint task forces with Guangdong province to enhance the city’s testing and isolation facilities and to secure a stable supply of fresh vegetables and medical goods.

Sources: The Standard, VOANews, South China Morning Post

In the following week, his words were echoed by Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s repeated dismissal of the need for total lockdown. But on March 2, Health Secretary Sophia Chan suddenly said that a lockdown had not been ruled out, fueling rumors and sparking another wave of panic buying.

Comments Cheung, “We would (have) probably (updated) on social media instantly, by highlighting not only how Sophia Chan’s words contradict with her colleagues’, but also how people rush to buy groceries as a follow-up, much faster than mainstream media like newspapers.”

Cheung says that independent media outlets are more flexible in style compared to mainstream media’s bureaucratic practices. She points out that the social impact brought by such flexibility and boldness is even more obvious when reporting news that is not part of the government’s agenda. The independent media outlets’ use of social media also enhanced their speed in spreading information.

By comparison, the mainstream media are heavily dependent on traditional methods of disseminating information — TV, radio, and print. And with many of the owners of the private mainstream media having major business interests in the mainland, these outlets are unlikely to engage even in positive criticism of the government, especially now under the National Security Law.

The very few brave enough to post a critique do so with a lot of caveats and are walking on eggs. For instance, a commentary submitted to the local newspaper Ming Pao last February questioned the lack of facilities to achieve the zero-case stance. The paper published the piece, but it attached this paragraph at the end of the article: “If the current affairs articles published on this website are critical, the purpose is to point out the errors or shortcomings of the relevant systems, policies or measures; urge the correction or elimination of these errors or shortcomings; and to improve them through legal channels. There is no intention to incite others to criticize the government or arouse hatred, resentment, or hostility from other communities.”

“To be frank,” says Victor, “I find the government’s tactics on defeating coronavirus more troubling than people getting infected. What will happen next? No one knows. We can only fend for ourselves.” ●

Stella Tsang is a freelance journalist with a focus on mainland China and Hong Kong issues.