It has been a year of living dangerously for most of the people of Myanmar, and it’s not only because of the virus that has wreaked havoc across the globe. Since February 2021, when Myanmar’s military staged a coup and declared itself in charge of the entire country, some 1,500 people have lost their lives because of the junta, according to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (AAPP). The rights organization, which has offices in Mae Sot, Thailand and Yangon, also says that as of Jan. 25, 2022, at least 8,788 people are under detention and that 84 people, including two minors, have been sentenced to death. It emphasizes that these figures are only what it has verified and that the actual numbers could be higher.

Amnesty International has observed as well that the military has begun to use its infamous “four cuts” strategy on the new People’s Defense Force — the armed wing of the National Unity Government (NUG) — “with devastating consequences for the civilian population.” Previously, the strategy, which calls for cutting off essential supplies, was used by the military against Myanmar’s ethnic armies.

The NUG was formed in exile by Myanmar legislators, most of them members of the National League of Democracy (NLD) who were elected in the 2020 elections, and other political stakeholders. The NLD had been poised to reassume leadership of the government when the military seized power on Feb. 1, 2021. The NUG has been lobbying to be recognized by the international community as the legitimate government of Myanmar and has called for a “people’s defensive war” against the junta.

Since the coup, some 295,000 people have been displaced while more than three million Myanmar citizens are believed to be currently in need of humanitarian assistance. The military has also razed communities to the ground in apparent attempts to crush popular resistance, even as it arrests and tortures — many times to death — scores of its critics.

More than 100 houses were burned down on Oct. 29, 2021 in Thantalang Township, Chin State. (Photo courtesy of a citizen journalist)

Among its early victims were two Muslim members of the NLD. In separate incidents last March, they were taken away at night by police and soldiers. The day after they were hauled off by authorities, their respective families were called to collect their bodies. Says one researcher at a think tank in Yangon: “Arresting a person at night and releasing his dead body (to relatives) the next morning is obvious evidence that the military tortured him to death overnight. If they cannot find the targeted people, they arrest the family members and hold them hostage.”

“It is time to break the culture of impunity among these military leaders,” says the researcher. “All of their hands are full of blood. We cannot let them get away this time.”

A brutal crackdown

When it ousted the newly re-elected government led by Daw Aung Suu Kyi a year ago, the Tatmadaw — as Myanmar’s military is known — had probably assumed that it could quickly tamp down any resistance to its rule. After all, it had been able to keep the country in its iron grip for decades, before it finally allowed Daw Suu Kyi’s NLD, which had a landslide victory in the 2015 elections, to form a civilian government. And even then, the military ensured that it still held much of the power in government.

But the Tatmadaw apparently underestimated the determination of the people of Myanmar to assert their right to choose their leaders. Since the coup, many people across the country have made clear that they disapprove of the Tatmadaw’s return to power, and have protested in the streets and online. In response, the military has fired live rounds at protesting crowds and gone after people it believes to be leaders and supporters of the growing civil disobedience movement.

Indeed, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the military has targeted and attacked medical frontliners who had been at the forefront of protests during the coup’s early days. In the first 10 months of junta rule, there were more than 100 raids of hospitals and 284 arrests of health care workers. At least 31 medical frontliners were also killed.

Rights advocates and journalists are among the military’s targets as well. One month after the coup, the military identified 16 labor civil society organizations (CSOs) as unlawful associations even as it revoked the licenses of several media outlets. CSO workers have been tailed and interrogated, and their offices and homes raided. Says one CSO employee: “When the military started targeting and arresting CSO people, I decided not to go to my office in Yangon. The next day our office in Chin State was raided.”

Another CSO worker who has relocated from Yangon to somewhere near the Myanmar-Thai border says that they are threatened not only by the military but also by pro-military groups called the Pyusawhti.

“One of the reasons I had to leave my house is because of Dalan (military informers) and Pyusawhti,” says the CSO worker. “They are quite threatening not only to me but also to my family.”

“I cannot stay in Yangon anymore,” adds the CSO worker. “Both our office and homes were raided. That is why I decided to come here (border area), but coming here is not that easy.”

To keep operating inside Myanmar, many CSOs have redirected their focus from rights advocacy to more “benign” activities such as welfare and vocational assistance.

“We have to change all of our activities to those not related to rights or politics,” says a senior staff member of a rights CSO in Yangon. “For safety and security, we suspended all the activities relating to these areas and focus more on welfare and development instead.” Some CSOs have also taken down their Facebook pages and websites.

But doing all these has not stopped the military from hounding the CSOs. As a result, many are operating in secret even though they are not doing anything illegal. A strike leader from the University Students’ Unions Alumni Force (USUAF) says, “There is no civic space anymore in Myanmar. All the CSOs have to operate underground since they cannot do anything inside the country freely.”

“Everyone is at risk”

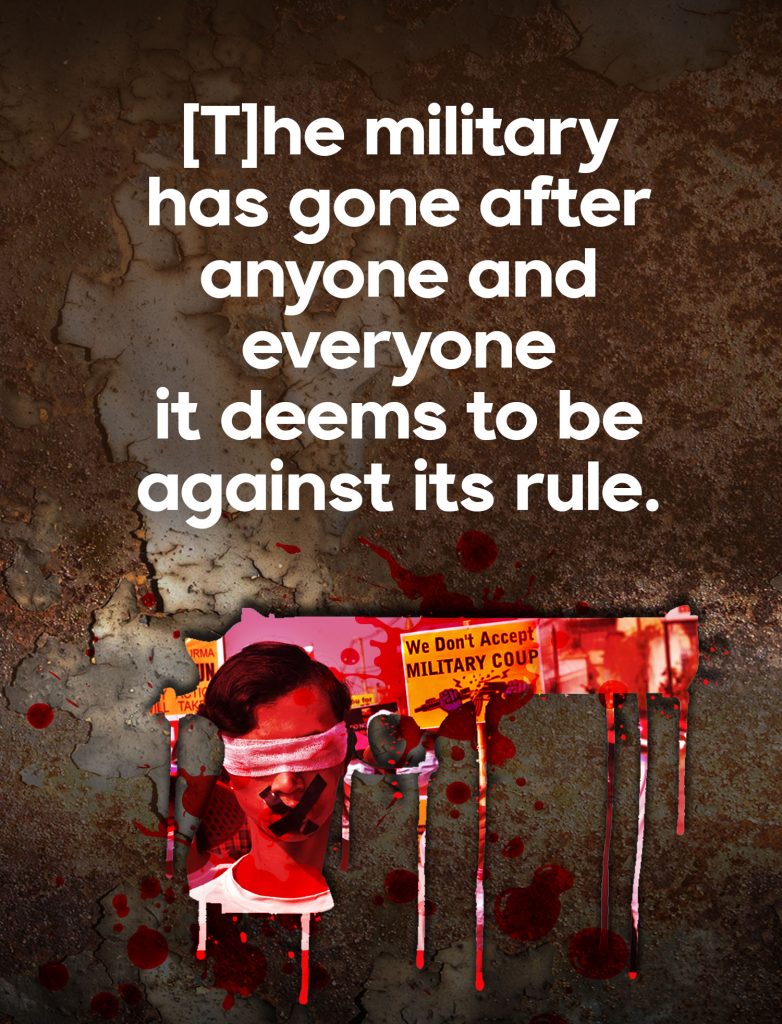

In truth, the military has gone after anyone and everyone it deems to be against its rule. In Chin and Kayah States, it has raided and attacked Christian churches and Buddhist temples and monasteries. Two workers from the international CSO Save the Children were also among the 42 civilians killed by the military last Christmas Eve in Hpruso Township, Kayah State. The victims were said to have been tied up and burned alive inside vans.

Two weeks earlier, 10 villagers, five of whom were in their teens, were reportedly also burned alive by the military in Salingyi Township, Sagaing Region, supposedly in retaliation for an ambush on a military convoy in the area.

The NUG’s Minister of Human Rights meanwhile says that 103 people, the majority of whom were non-combatant civilians, were killed during massacres sponsored by the military in July, August, and September 2021. The BBC has also reported that at least 40 men were tied up with ropes, beaten, tortured, killed, and buried in shallow graves during four separate incidents in July last year in Kani Township, a resistance stronghold in Sagaing Region.

“In Myanmar, even the right to live — a basic human right — cannot be guaranteed anymore under the military junta,” says the USUAF strike leader. “Everyone is at risk of being killed.”

When they are not burning people alive, the soldiers have reportedly been burning down homes. Between February 2021 and January 2022, soldiers have destroyed and burned nearly 2,000 houses across 96 locations in Myanmar. In Thantalang Township in Chin State, more than 160 homes were burned down by the military last October.

Victims of the military junta’s brutal repression of individuals perceived to be against its rule include those who were burned alive inside vans in December 2021 in Hpruso Township, Kayah State. (Photos courtesy of Karenni Nationalities Defense Force)

Unsurprisingly, more and more people, especially the youth, have been taking up arms and fighting back. Some groups are also joining forces with the ethnic armies. One young armed resistance member says, “We have tried all non-violent ways and it did not work well. I was not interested in politics before, but I know the coup and killing people is too much. I am here because I believe armed resistance is the only way to bring the military dictatorship down.”

But there are still many people who believe that non-violent resistance has value in the struggle to end military rule in Myanmar. The USUAF strike leader notes, “The whole country of Myanmar supports the armed resistance. But it can only be a pressure mechanism and for creating new liberation areas. It needs to combine with non-violent ways.”

One key factor in the effort to end the junta’s rule is international pressure, observers say. Myanmar CSOs agree, which is why during the early days of the coup more than a hundred of them sent an open letter to the UN Security Council, asking it to impose a global arms embargo against the junta. A researcher from a CSO in Yangon comments, “Currently, the international community has limited options to intervene in Myanmar. But (governments) still can try not to legitimize the military junta by imposing effective sanctions, targeting the income sources of the military junta, and implementing an arms embargo against it.”

For sure, even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has been forced to take a hard look at its “non-interference” policy because of what has been happening in Myanmar, one of its member countries. Last October, it excluded junta chief Min Aung Hlaing from a major ASEAN summit because, said the group’s current head Brunei, the Myanmar military government had made “insufficient progress” on a peace-restoration roadmap it had agreed to earlier with ASEAN.

The junta responded by saying that it was “extremely disappointed” with ASEAN’s decision. Soon after, however, it announced that it was releasing more than 5,000 political prisoners — a move that was read by many as a bid to win brownie points with ASEAN and the rest of the international community.

The junta did release some prisoners, but observers say that they numbered in the low hundreds and nowhere near the thousands that the military had claimed. Many of those released were also quickly re-arrested. ●

Jesua Lynn is an independent researcher and peace-education trainer. He has authored and co-authored more than four publications in Myanmar in the fields of human rights, hate speech, youth activism, and peace building.