Waterlogged paddy fields glisten in the sun as 40-year-old Pushplata Maurya sets off on her scooter for Beejapur, a little hamlet in Bhadohi in Uttar Pradesh, northern India. She drives straight to a small house on the periphery of the village, where marginal farmer Tara Devi is weighing a sack of grain on a scale hanging from a tree in her courtyard.

“My neighbor had borrowed this grain in May this year,” Tara Devi says as she greets Maurya. “Now she has returned it with 25 percent interest.”

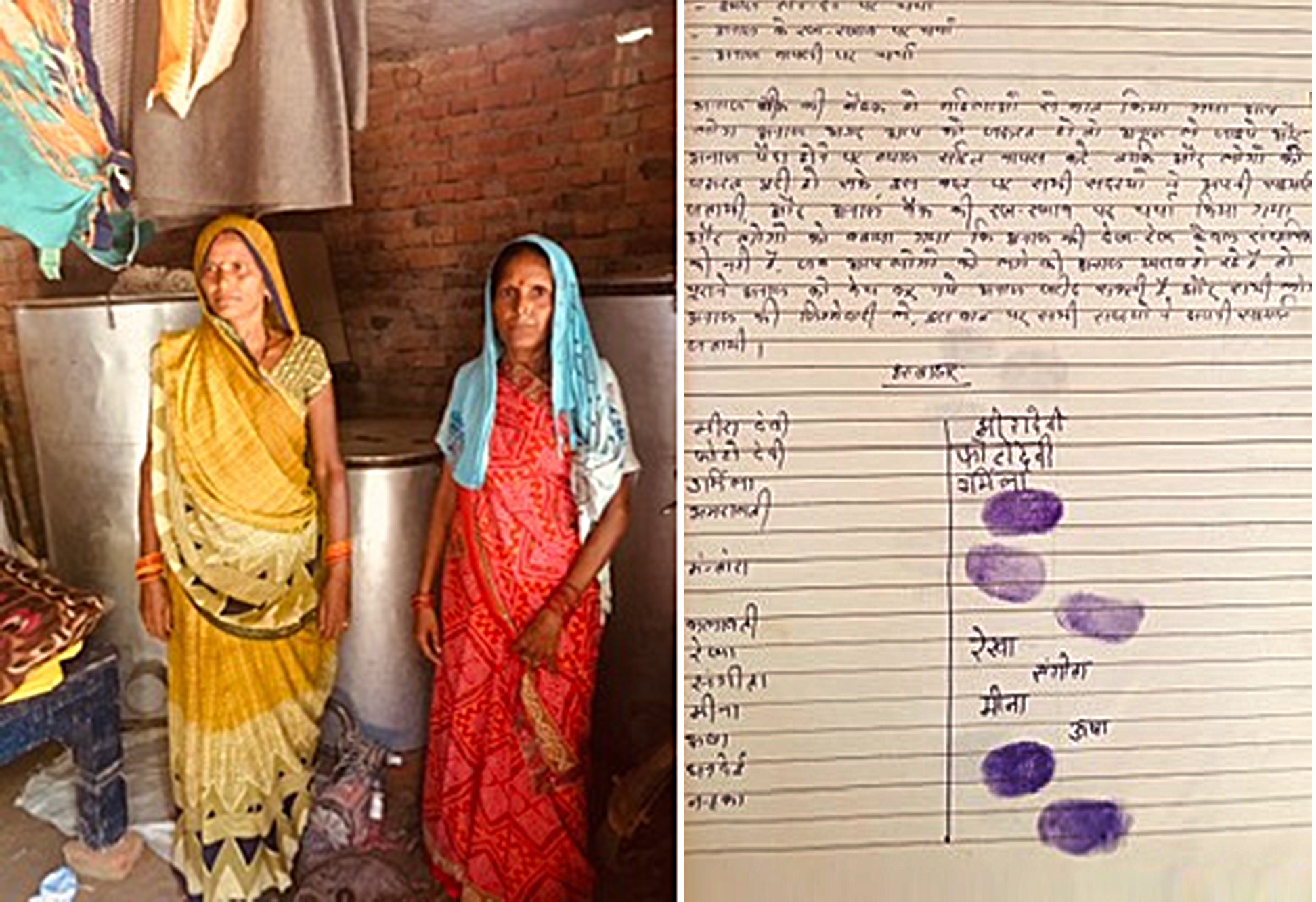

Maurya examines Tara Devi’s ledger, filled neatly with entries and thumb prints. She tells the farmer, who is illiterate, “You’re managing the bank very well.”

But this is no ordinary bank, and Tara Devi is not an ordinary bank manager either. Set up in 2017, this grain bank with a capacity of 500 kg has been a source of food security for Tara Devi, as well as the entire community of Beejapur. It has 50 members, each of whom has contributed two kilograms of rice to join the bank. Shramik Bharti, an Uttar Pradesh-based NGO focused on the empowerment of the poor, put in 400 kg of rice so that the bank could maintain a corpus of 500 kgs.

Shramik Bharti developed and implemented the grain-bank project, which it started in farming communities near Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh in 2011. So far it has set up over 200 grain banks in five of the state’s least developed districts, with a combined storage capacity of more than 100 metric tons.

The grains vary depending on the community staple, which is usually either rice or wheat. A small number of grain banks have started storing pulses (legumes or dal) as well. Members borrow up to 100 kg of food grain at a time whenever they are in need, and return that with interest within six months, which is also about the time it takes for a crop to be ready for harvesting.

Tara Devi (in red) has been operating the Beejapur grain bank since 2017. She keeps a meticulous record of transactions (right), signed by borrowers with their thumbprints. (Photos by Geetanjali Krishna)

On this particular day, though, the members of the Beejapur grain bank are gathered at Tara Devi’s house for a meeting. The members say banks like this one have been invaluable. Although they grow food staples themselves, most of them experience periodic food shortages.

“Many marginal farmers, like others across India, face shortages of food grains at specific times in the cultivation cycle,” explains Rakesh Pandey, who heads Shramik Bharti. “Usually, the time of the year when they need capital to buy seeds and fertilizer for the new crop is also when their food supply stored from the previous harvest runs low. Food grain prices in the market are high at this time, and farmers often don’t have money in hand to purchase them.”

Less empty bellies

Dependent on the vagaries of a capricious monsoon for irrigation, farmers like Tara Devi can never assume they will get a good harvest. Food grain banks offer an easy, if partial, assurance of a ready food supply.

Before the pandemic, members mostly borrowed from these grain banks whenever they had wedding or death feasts to host. But during the pandemic, the ensuing job losses, and economic distress, these banks have ensured that some 6,000 agricultural laborers and marginal farming families in rural Uttar Pradesh have not gone to sleep hungry.

For sure, India has made considerable progress in tackling hunger and malnutrition in the past two decades. But the conditions on the ground in little villages like Beejapur suggest that the progress has been uneven.

In the 2021 Global Hunger Index, India is ranked 101st out of the 116 countries assessed, with its level of hunger considered “serious.”

Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) meanwhile show that between assessment years 2017 and 2019, India had 189.9 million undernourished individuals. This figure rose to 208.6 million (2018-2020). FAO defines Prevalence of Undernourishment as an “estimate of the proportion of population whose habitual dietary intake is less than the minimum dietary energy requirement that is required for normal, active, and healthy living.”

In Beejapur — and much of rural Uttar Pradesh — it’s not hard to see how the FAO figures came about.

The paucity of job opportunities and increasingly poor returns from agriculture have forced most of the able-bodied men in Beejapur to migrate to cities for work. There, they are employed mostly as labariya — daily-wage laborers, mostly in the construction sector. The women stay behind to till their meager landholdings, dependent upon the variable amounts of money their menfolk manage to send home.

“My landholding is so small and I have so little help for managing it, that for years I have only grown enough for our own consumption,” says Beejapur grain bank member Arti Devi. “So earlier, if my crop failed, I often did not have enough to feed my children.”

“Most of the marginal farmers we’ve spoken to said that, during times of food scarcity, they’d be forced to borrow food grains from bigger farmers and return them at the time of harvest,” says Pandey. “In return, they would have to pledge to harvest the lenders’ fields first and at a lower wage.”

Photo Devi and her husband, who grow tiny amounts of rice, wheat, and vegetables on their little plot of land in Beejapur, say that the situation was bad even before the pandemic.

“Since 2017, the canal behind our village has been flooding our fields, causing our crop to fail,” Photo Devi says. “As a result, we have barely been able to grow enough for our own sustenance, let alone to sell.”

But the lockdown made things worse. Cut off from the market, farmers found it difficult to sell their harvest and the handicrafts some of them work on for additional income.

Arti Devi’s husband was among the thousands of migrants who made their way back home from Mumbai after the first nationwide lockdown was declared. “We were relieved to see our menfolk return home and safe,” says Arti Devi, who weaves carpets and works as an agricultural laborer to supplement the family income. “But without any income, opportunities to work, and with more mouths to feed, we worried about how we were all going to survive!”

A lifesaver during the pandemic

In the two pandemic years, almost every one of the Beejapur bank members — mostly landless agricultural laborers and carpet weavers — has had to borrow food grain at least once. Tara Devi says, “Without this bank, the economic deprivation created by the lockdown would have forced many of us to borrow money at high interest rates from private money lenders simply to buy food!”

During the two nationwide lockdowns imposed in India (the first in 2020, and then the second in 2021), the Beejapur grain bank loaned 348 kg of food grain, of which 292 has already been returned. It currently has 156 kg of rice.

Before the pandemic, members usually borrowed food grain whenever there was a wedding or terhai (13th-day death ceremony observed by Hindus) in their family. Non-members rarely approached the bank for food loans. The pandemic changed that. “During the lockdown,” Tara Devi says, “we loaned food grain to at least 50 to 55 outsiders.”

Shramik Bharti has observed that in the pandemic years, some grain banks supported their worst-off neighbors with free food grains. Others earned so much grain in interest that they sold the excess to upgrade their storage facilities. (The interest rate is usually 25 percent, but this may vary depending on the community.)

Coming together to ensure that they can feed themselves as well as their community has given members a sense of being in control of their own well-being. Tara Devi also observes that members rarely default on their loans.

“In fact, in all our grain banks, we have seen that members always return the grain they borrow as quickly as possible,” says Pandey. He adds that the experience of grain banks has primed many local women to join other collectives.

In the nearby village of Jamunipur, women have formed a self-help group. “Our SHG collects small contributions from members and offers loans of up to INR 15,000 (about US$200),” says community member Meera Devi. “It ensures that we have some financial support of our own.”

Others aver that while the grain bank keeps them food-secure, the SHG helps them with small loans they need for agricultural inputs, such as seeds and fertilizers. This has minimized their dealings with private money lenders.

Modest, but effective

FAO has recently estimated that instead of being on track to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030, the number of people across the globe affected by hunger could surpass 840 million, or 9.8 percent of the population. That’s not even taking into account the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this scenario, the community grain bank model offers a small-scale but easily replicable solution.

In Jamunipur village in Uttar Pradesh, Meera Devi (left) runs a tight ship and inspects grains (right) to ensure they are of the same quality as what was borrowed. (Photos by Geetanjali Krishna)

Pandey estimates that each bank costs about US$205 to set up, excluding Shramik Bharti’s staff and administrative expenses. Training of the community members is critical to the success of the grain bank.

“As most of the members are marginal farmers, they are already skilled at weighing and storing food grain,” he says. “Once trained, members have mostly been very successful in running grain banks on their own, with weekly visits from our staff.”

As the bank members’ meeting in Beejapur ends, the women leave, chatting and laughing.

“How confident they seem!” says Maurya, getting back on her two-wheeler. “I have worked with many NGOs since 1995, but have not seen anything as impactful as these grain banks.”

Tara Devi rolls up the mat after the women leave. Glancing at her husband who is sitting on a charpoy (a light bedstead), she wonders when he can return to Mumbai, where he used to work as a plumber.

“Our lives are so precarious,” she muses. “One month your husband sends home a decent amount of money, or the harvest is good, and everyone in the family eats well. The very next month, if he doesn’t get enough work, or if unseasonal rains spoil the crop, there aren’t enough rotis for all of us to eat.”

Now, though, they have the grain bank to count on. Says Tara Devi: “It has taught me that food is our only security. Food is the biggest capital in the world.” ●

Geetanjali Krishna is the co-founder of The India Story Agency, which specializes in telling environmental, public health, and social affairs stories from South Asia to the world. One of the 16 awardees of the Global Health Security Grant 2021 by the European Journalism Centre, she is a contributing editor at Business Standard, an Indian daily. Her recent by-lines can be found in Times, The British Medical Journal, BBC Future, The Third Pole, and Business Standard.