Editor’s note: Pro-democracy protests in Thailand amid an unprecedented global scourge that has sent the country’s once-thriving economy reeling and fraught politics into a tailspin show no sign of abating. On the contrary, public demonstrations, steeped in seething anger directed at the establishment and a now unpopular monarchy (both widely blamed for the country’s bungled COVID-19 response), have taken to more aggressive acts: arson attacks on royal arches and Thai King Maha Vajiralongkorn’s portraits.

The state’s arsenal of repressive tools — the use of police violence against demonstrators, the filing of criminal charges against protest leaders (and the consequent denial of bail), and the revival of the Royal Defamation Law in the time of coronavirus — has done little to dissuade protesters from taking to the streets and openly defying the monarchy and torching the images of the King.

The resurgence of royal defamation charges, based on the draconian Section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code and the unwarranted strict implementation of this law in today’s highly charged political milieu, raise the specter of more violence on both camps. This feeds into an endless cycle of instability that gets more worrisome by the day.

An escalation of symbolic actions by pro-democracy protesters took place after the repeated use of force against protesters by the police and legal charges against its leading figures. But when it comes to burning portraits of the King, the state uses the royal defamation law to handle the problem.

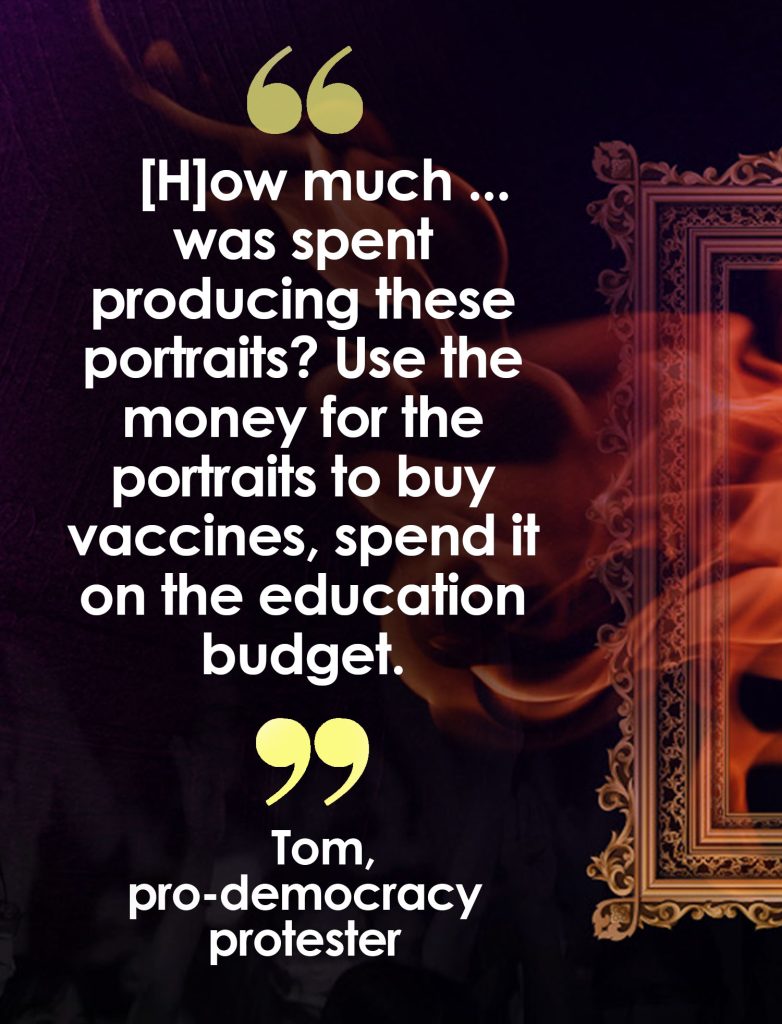

Tom (not his real name), a pro-democracy protester, burned down a portrait of the King in Bangkok after their group evaded an ambush by pro-royalists one night in September.

“Please just look at how much budget was spent producing these portraits?” he says. “If we keep burning them, and they are symbols that we don’t want, they won’t make any more portraits. Use the money for the portraits to buy vaccines, spend it on the education budget.”

“People may not understand why. People may wonder if it is anger,” Tom continues. “But if we have explained things this way, they will get the picture about why we burn them. We burn them to let them know that we don’t want them.”

Firefighters try to extinguish a fire on the Royal Commemorative Arch along the Chaloem Maha Nakhon Expressway in Bangkok in September 2021.

Burning rubbish and official property has increased in the past three months, and especially after the protesters were halted in their tracks as they marched in the direction of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha’s house at the Din Daeng intersection in Bangkok August. This led to nights of confrontation between protesters and the police.

Royal arches and portraits of the King are the targets of arson, despite the Kingdom’s controversial lese majeste law, Section 112 of the Criminal Code, that carries a three-to-fifteen-year jail sentence and which has been criticized for its broad interpretation in the Kingdom’s recent political history.

Beyond legal consequences

Tom was later arrested and charged with royal defamation for the arson. He is not the only one to be arrested.

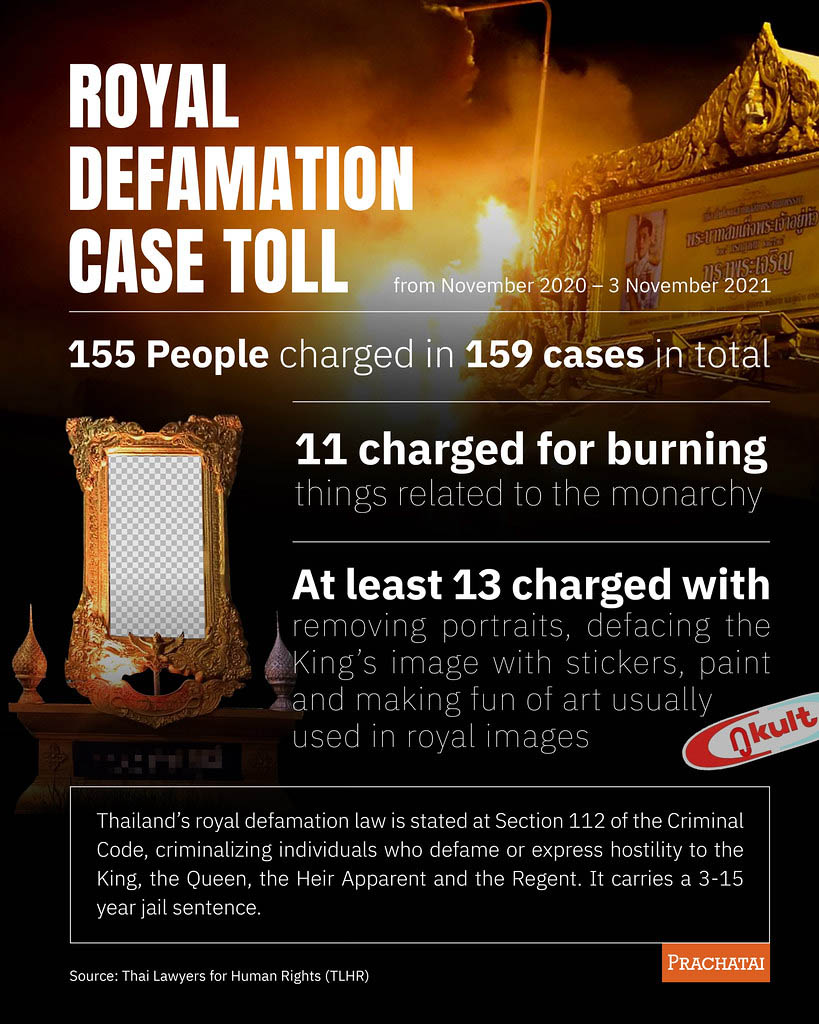

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) reports that, between November 2020 and November 3 this year, 155 people in 159 cases have been either charged or put on trial under the royal defamation law. Eleven out of at least 19 arson cases allegedly involve burning objects, like portraits or arches, that are related to the monarchy.

Besides the arson cases, there are 13 royal defamation charges involving the removal of portraits, defacing the King’s image with stickers or paint, and parodying the style of art usually used in royal images.

Regarding arson, Sawatree Suksri, a law lecturer from Thammasat University, says the act itself can be counted as arson or mischief but should not be counted as defaming, insulting, or expressing hostility toward the King, Queen, Heir Apparent, or Regent as provided under the royal defamation law.

Unlike the law in the days of the absolute monarchy that clearly criminalized damage done to symbols of the monarch and the nobles who governed in his stead, Sawatree says that the laws criminalizing injury to the monarchy that came later did not specifically include surrounding figures and symbols as such.

Therefore, the royal defamation charges should be based on an interpretation that the act has a direct intention. While the burning by itself may fit the definition of arson or mischief depending on what they burn, it does not constitute a direct threat to harm or murder the subject in the case of burning someone’s image.

The Thammasat University law lecturer says the content of the royal defamation law is similar to other laws in the Criminal Code. Thus, it should be interpreted by similar standards. She cites a European Court of Human Rights ruling that the burning of photographs of the King of Spain by protestors was a form of freedom of expression. This example could be used to limit the scope of the royal defamation law.

On the other hand, Poonsuk Poonsukcharoen, a TLHR lawyer, says it is difficult to describe the use of Section 112 based solely on the logic of the law. From late 2018 onwards, no royal defamation charges were brought against offenses that were similar to cases today where this charge is applied.

At that time, Prayut was reported to have claimed that no royal defamation charges were filed because of the King’s “generosity.”

But in November 2020, after a surge in pro-democracy protests, the prime minister announced that “every section of the law” would be used, and so royal defamation charges reappeared.

“It points out the unpredictability in the use of Section 112, because, for one period of time, after the coup, it was the policy to use military courts,” says Poonsuk. “The trials passed [heavy] sentences for each offense.

“For almost 10 years until 2018 [two years] after the King (Bhumibol Aduyadej) passed away, there was another wave of prosecutions,” Poonsuk continues. “After the succession of King Rama X (Vajiralongkorn), there was a policy change in the direction of not enforcing [Section 112] by every organization.

“The worry may be the strict enforcement of Section 112 over the past year or so. The overall picture is that Section 112 is used in every case that concerns the monarchy,” Poonsuk points out. “This is worrying because it points to unpredictability in Thai society where for one period of time, there were no Section 112 cases at all.

“Whatever you did, it wasn’t an offense, or even if there was a prosecution, some cases are unbelievably dropped. But, at another time, whatever is done that is related to the monarchy is all interpreted as Section 112.”

Bizarre policing

Most of the arson cases led to arrests in late August. It will take time before these cases are brought before the courts. The latest court case of burning an image of the King was in 2018 when the Appeal Court overturned the conviction of six people who burned down a royal arch in Khon Kaen Province in northeastern Thailand.

The reason given by the court was that the defendants had no intention to violate the royal defamation law. It should be noted that the ruling came at a time when the enforcement of the royal defamation law had practically ceased. The direction of the courts in royal defamation cases in the near future will be interesting to observe.

Poonsuk says there are many irregularities in police procedures regarding arson cases related to the monarchy. For example, in a case in Khon Kaen Province in September 2021, the police tried to interrogate two suspects separately without allowing them to contact a person they trusted.

There were two other cases where the police made arrests and seized the suspects’ phones without a warrant. The police justified their acts by saying that all this was done with the suspects’ consent, confirmed by documents that they had them sign.

In the case of Tom, the police also tried to remove one suspect for interrogation and bar the presence of a lawyer, which is a violation of one’s constitutional right. After the lawyer successfully insisted on entering the room, he found the suspect shaking with fright. It was reported that he may have been subjected to a police beating.

Of the people arrested that night, Tom and another suspect suffered physical mistreatment at the hands of the police. In Tom’s case, his head was pressed onto a desk and was pushed down to his knees after he kept on refusing to allow the police access to his phone.

“They said to please cooperate well with the police. I was like, getting into my phone has nothing to do with Section 112 at all,” asserts Tom. “Why did I have to turn it on for them? It’s not the Computer Crime Act. If it’s the Computer Crime Act and you had a warrant from the anti-cybercrime police, I would have opened it. But they didn’t.”

Many juveniles under investigation for arson cases, who had their phones seized, could not call their parents or guardians. Personal issues also come to play as some juveniles either did not want to contact their parents or their parents were stuck at work and could not come, causing difficulties in the investigation and bail processes.

Piyanut Kotsan, the director of Amnesty International Thailand and who has participated in the “Child in Mob” campaign promoting and protecting children’s rights in protests, says some of the youth arrested at Din Daeng have difficult relationships with their family members. This exacerbates the situation when they are arrested as some of them either could not tell their family members that they went to the protests, they lived apart from them, or they had lost them due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Legal harassment feeds retaliation

From Piyanut’s observations, the escalation of violence among protesters is an expression of anger toward the state’s failure to control the damage from the COVID-19 pandemic. This may explain why these protesters do not seem discouraged by repeated royal defamation charges against the pro-democracy movement’s leading figures, and thus continue to gather and take on the police.

She sees the gatherings as political because the targets of their violence and arson belong to the state such as police or government property. This comes in response to the way the crowd-control police have dispersed protests in the past.

“If politics was OK, there would not be anger or people coming out to express themselves in this way. I think they could express themselves without this kind of anger,” Piyanut explains. “You also have to see that what they have been doing to handle this over the past month and more does not work, but they still do it.”

“Why don’t you divert the budget for rubber bullets and tear gas into taking care of the people’s welfare?” asks Piyanut.

Sawatree says that allowing a broad interpretation of royal defamation will put an overwhelming burden on the police and judges in the investigation and trial processes. She also sees the sharp rise in arson cases as reflecting the people’s anger toward disproportionate prosecutions and questions about the monarchy’s involvement in politics.

Calls for the amendment or repeal of lese majeste, or Section 112 of the Penal Code, continue in Thailand as many feel the provision to be vague and arbitrarily used by the government against its citizens.

“We also can’t deny that this administration tries to link itself to the power of the monarchy,” Sawatree adds. “So this pulls [the monarchy] down quite a lot. Once it is pulled down, it can’t stop people from thinking, as a consequence, ‘hey, does the monarchy have a political role, or is it involved in the country’s administration?’ … And when the national administration doesn’t [seem] to be working, and [seems] to have many problems … because the protests to have the government resign haven’t worked, it keeps on escalating.”

Sawatree suggests that not allowing people to speak their minds can provoke them into resorting to violence and ignoring the laws that are used to mistreat them. Negotiation and opening space for criticism under the framework of the law should solve the tension.

Poonsuk also thinks that the violence employed by the protesters has to do with the use of the royal defamation law as a political tool. She suggests the authorities drop the ongoing cases because the offenses are unrelated to the charge and it is not in the public interest. In the long term, Section 112 should be amended and the importance of the rule of law established in Thai society.

“When we talk about being in a state ruled by law, or the rule of law, it has to be firm and certain and the law must not look at who it is dealing with. But the use of Section 112 clearly shows that it is selectively used against some groups, some cases, and depends on the whim of one organization or one individual to a certain extent…. It points out the uncertainty that is not decided by the law, but by something more than the law, because the law has always been the same while the situation has switched back and forth,” says Poonsuk.

X (not their real name), another protester who set fire to a portrait of the King, says the monarchy should be open to criticism and see that the arson he caused was an expression of his anger toward the use of violence against the protesters by the crowd control police.

“I feel that it’s not wrong to burn things. But people’s rage makes them do it.” ●

This article was first published by Prachatai on October 21, 2021, updated on November 9, 2021. It is republished here by the Asia Democracy Chronicles with permission.