ommuting” is synonymous to the word “agony” for 13 million residents of Metro Manila, the nation’s capital region. Going to the workplace from home and back has been a constant source of distress for millions of Filipinos in one of Asia’s most congested metropolitan areas.

Filipinos are no stranger to the apocalyptic scenes of commuters struggling to get a ride on Metro Manila’s main thoroughfares. This includes enduring long hours of queues for public utility vehicles and trains that last well into the night, and the exhausting travel time in cramped buses and jeepneys — one of the most ubiquitous modes of transport in the Philippines — crawling through heavy traffic.

In 2019, a well-known navigation app, Waze, named Metro Manila as one of the cities with the worst traffic in the world. A study conducted in 2017 by the Boston Consulting Group, commissioned by ride-hailing app Uber, showed that a commuter in Metro Manila spent 66 minutes in traffic every day, the third longest in Asia.

The heavy traffic has taken its toll on the physical and mental health of commuters.

Many are used to sacrificing hours of sleep to wake up very early to beat the rush hour “carmageddon.” Others have to walk long distances in unsafe areas to come to work on time or be home safe with their families. These are just a few of the typical ordeals a regular commuter has to endure every single day.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the daily agony even worse.

Since March 2020, the Philippines has been placed under various levels of community quarantine, making the country’s lockdown the longest in the world. Abrupt restrictions on public transportation left commuters like headless chickens on the roads. Even healthcare workers, who play significant roles during a health crisis and use public transport regularly, were not spared.

As the lockdowns eased in the months that followed, buses, jeepneys, trains, and even tricycles were forced to adapt to the so-called “new normal.” Drivers were required to regularly sanitize their vehicles and install plastic barriers as part of health and safety precautions.

According to AltMobility PH, these measures have increased the cost of public transportation.

“Commuting is more expensive now across all public transport modes,” said Jedd Ugay, chief mobility officer of AltMobility PH. For instance, local governments have restricted tricycles to one passenger at a time. This means a passenger needs to pay more for a “special ride.”

While the new health protocols take into account the welfare of commuters amid the pandemic, the riding public now has to choose between safety or savings.

“For most people, public transport is their primary choice. Regardless of whatever state our transport system is currently in, people still need to undertake essential trips for essential purposes. It is inevitable,” Ugay added.

As Filipinos struggle to avoid the deadly coronavirus, they still have to contend with the agony of daily commuting, itself a malady that seems to have no cure in sight.

“Commuting in Metro Manila right now doesn’t feel humane. Just see the pictures of commuters daily or experience it yourself. There is no dignity in commuting in Metro Manila,” Ugay said.

Thousands of commuters pack bus stops and other transport stations, enduring long and exhausting queues across Metro Manila, after the government imposes a 30-day lockdown or ‘community quarantine’ , across Luzon, the country’s largest and most populous island region, effective March 17, 2020 to contain the rise of COVID-19 infections.

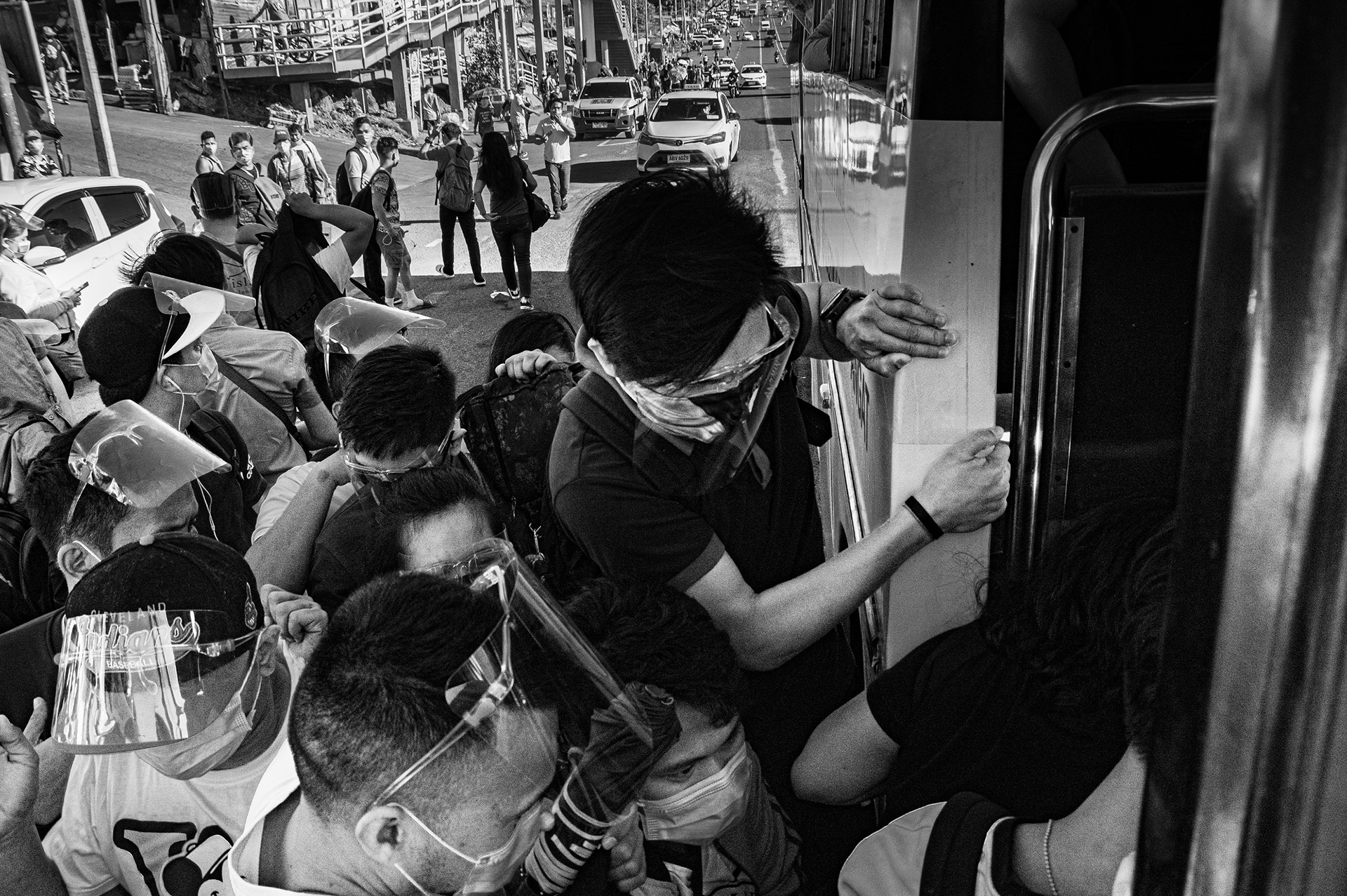

The abrupt implementation of the lockdown and the restriction of public transportation left widespread confusion among commuters including essential workers stranded along main thoroughfares on 16 March 2020. Buses in Metro Manila were strictly advised to limit their capacity to 25 passengers aboard as part of the ‘physical distancing’ protocol. This resulted to more passengers unable to board buses immediately.

Desperate passengers cramp up in a bus disregarding ‘physical distancing’ protocols and passenger limit on 16 March 2020. Thousands of commuters around the city struggle to get on any available transportation before 12 midnight of March 17 — the effectivity of the strict Luzon-wide enhanced community quarantine (ECQ). Many others are left without a choice but to walk several miles in order to reach their destinations on time.

Overcrowded bus and long queues in PUV (public utility vehicle) stations are common scenarios during rush hour in Metro Manila even before the pandemic and is attributed to the lack of quality urban transportation system and infrastructure.

After months of strict lockdowns, authorities allow public transportation, including jeeps and city buses, to resume limited operations in June 2020 while imposing new health and safety protocols. These protocols include regular sanitization, installation of plastic barriers, and limiting passenger capacity to at least 50%. The new health guidelines have increased the cost of transportation, forcing commuters to choose between safety and savings.

Ervine Calaoagan, 27, a call center employee leaves his house in San Jose Del Monte, Bulacan, in the central Luzon region, before 6 a.m. to reach his office in Ortigas Centre in Pasig City on time. Ervine has been using public transportation since he started working 3 years ago. The COVID-19 pandemic posed new challenges for him, including his safety and budget during his commute.

As a regular commuter, Ervin takes the MRT then rides a bus in Kamuning in Quezon City, located northeast of the capital city Manila, every day. He used to travel for 4 hours from his home in San Jose Del Monte, Bulacan, to his office in Ortigas Center, a central business district in Metro Manila, and vice versa. He said his travel time has been reduced to 2 hours during the pandemic but had to endure higher fare rates implemented by transport companies. He used to spend Php90 (US$1.88) for his daily transportation budget. Today he spends almost twice that amount.

Ervine rides a regular non-airconditioned bus from Kamuning, Quezon City, late at night to his home in San Jose del Monte, Bulacan. He considers pre-pandemic commuting better despite heavy traffic and long travel hours. ‘Today, aside from waking up early, the fares are now higher, and sometimes you still have to walk all the way to the next bus stop or to EDSA Carousel,’ he says.

During the first lockdown at the start of the pandemic, 33-year-old Kristy Reyes, a nurse working at a government-run hospital in Quezon City, had to walk for hours from her home in Cubao, a commercial center at the heart of Quezon City, to her place of work. ‘I had to hitch rides on any passing vehicles. I was even offered a ride by a livestock delivery truck and even a hearse,’ she says.

Kristy is scared of riding mass transportation after coming in close contact with a case of COVID-19 infection while on duty at the hospital last year. She favors taxis over crowded buses or the ubiquitous jeepneys, one of the most popular modes of transport in the Philippines, despite the much higher fare. From Php18 (US$0.88) daily, she now spends Php250 (US$5.24).

“They said it’s riskier, but for me it’s safer. I just pull the windows down and spray alcohol. It’s safer than riding a cramped-up jeepney. I just explain to the taxi driver that we need to have better ventilation and exchange of air inside the taxi. If it’s airconditioned, there’s a higher tendency to absorb the virus,” Kristy says.

On the final route to her home, Kristy walks along a dark neighborhood every night. Other than having to risk her safety again of having close contact with COVID-19 while on duty to make ends meet, she also experienced discrimination from the public, especially with PUVs.

“If you’re in a scrub suit, it feels like you are being discriminated. For example, tricycles won’t give you a ride. Sometimes some taxis will not stop for you if you’re in a scrub suit. So as a lesson, I change to casual clothes before I leave the hospital,” she says.

Commuters struggle to get on a bus on Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City after the government reimposed the stricter enhanced community quarantine in Metro Manila as well as in the provinces of Bulacan, Cavite, Rizal, and Laguna on March 29, 2021. COVID-19 cases in the country hit an all-time high in just a couple of weeks with hospitals reaching full capacity due to the influx of newly infected patients.

Increasing the capacity and number of public transportation vehicles in Metro Manila will benefit commuters and allow physical distancing. Advocacy group AltMobility PH says the government should prioritize commuters instead of private vehicles. ‘We should adopt a people-centered approach wherein the priorities should be according to pedestrians, bikers, public transport users, and private cars,’ says Jedd Ugay, chief mobility officer of AltMobility PH.

This story is one of the twelve photo essays produced under the Capturing Human Rights fellowship program, a seminar and mentoring project organized by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Photojournalists’ Center of the Philippines. ●