Khalid* is a dedicated journalist in Indian-administered Kashmir. His work on diverse issues has appeared in international, national, and local news outlets. Over the last few months, though, he has had bouts of depression and often thinks of quitting journalism.

“In Kashmir, practicing journalism these days can land you in jail,” says Khalid. The longstanding unresolved conflict between India and Pakistan has led to a climate of fear in the contested territory. Journalists have been beaten, interrogated by the police, and questioned about their reporting.

As a result, anxiety grips Khalid whenever his reports get published. He says, “I keep thinking, how can I defend my report if the police summons me for questioning?”

Journalism in Indian-administered Kashmir is going through a turbulent period. State oppression has led Khalid and his colleagues to censor themselves. Many journalists who spoke to Asia Democracy Chronicles for this report requested anonymity because they fear reprisal from the state.

A slow death

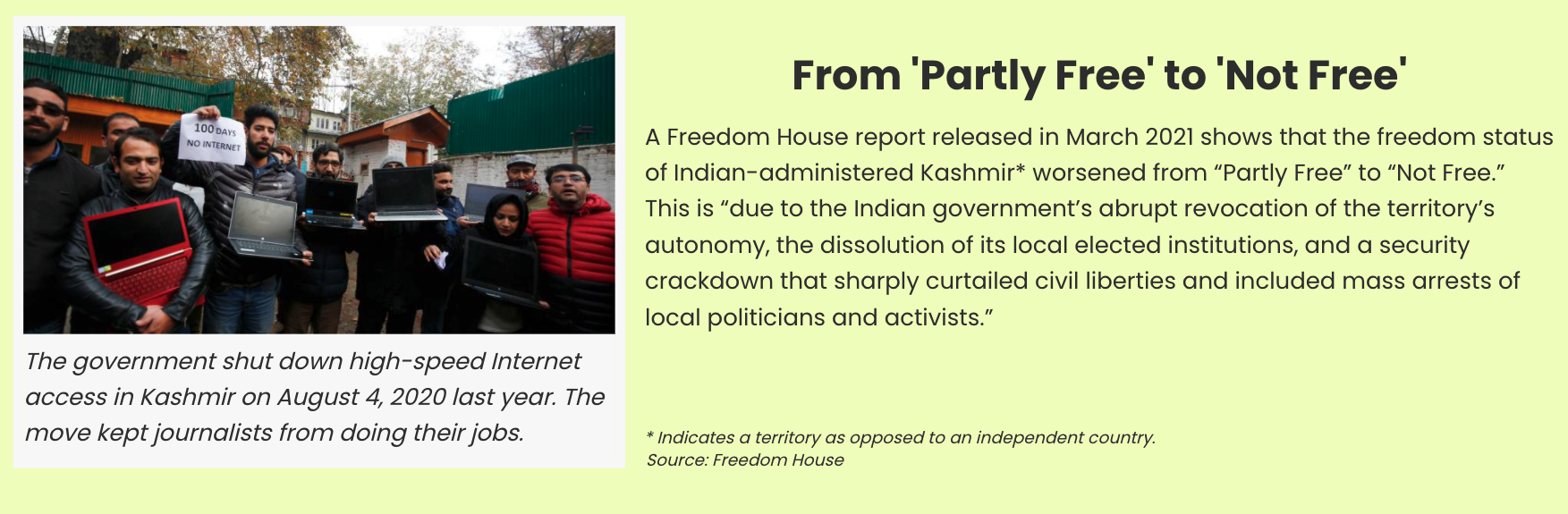

Reporting from the region, where India has deployed several hundred thousand forces to quell the rebellion that broke out in the late 1980s against Indian rule, has always been dicey. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party scrapped Kashmir’s autonomous status on August 5, 2019. The move stripped residents of many of their previous political rights and curtailed civil liberties, reports Freedom House. As journalists covered the issues in the conflict-torn region, the authorities have relentlessly intimidated them. The intense pressure has forced some of them to self-censor for their safety.

Kashmir has long been a flashpoint between India and Pakistan. Armed insurgency broke out in the disputed region against Indian rule in the late 1980s. Photo: Aamir Ali Bhat

This is what has happened to Khalid. He has become selective in the stories that he pursues and sometimes omits information to evade the wrath of the authorities. “Self-censorship is killing me,” says Khalid. “Writing the truth infuriates the state, which in turn gives you sleepless nights and makes you vulnerable. But hiding the truth kills you from inside.”

A senior journalist and scholar who requested anonymity agrees with Khalid. “The sustained harassment of Kashmiri journalists has a deep impact on the entire community, regardless of whether they were directly affected by the state violence or not,” says the scholar. “Of course, when you are beaten or tortured for doing your job, it takes a toll on your body and mental health. But the effects extend to other journalists in the field who start to fear the same persecution and begin to self-censor so as not get into trouble.”

On February 23, 2021, multimedia journalist Mir Junaid took to Twitter and defended a report that he wrote for the local online news portal The Kashmiriyat. The story described how government forces pressured a private school in South Kashmir’s Shopian district to participate in India’s Republic Day parade on January 26, 2021. “I’d reported the story with utmost honesty after speaking to the school authorities,” Junaid wrote on Twitter. “I merely did my job.”

After the story broke, the police booked Junaid and Yashraj Sharma, another journalist, for “inciting violence” and “provoking rioting.” Junaid wrote, “A case filed against me has troubled me mentally for the last few weeks. We must encourage future journalists, not silence a young reporter like me.”

A chilling account

On February 22, 2021, the Committee to Protect Journalists, a US-based watchdog for press freedom, asked the government to “stop targeting journalists because of their reporting” on Kashmir. In a detailed report published on March 5, 2020, Reporters Without Borders summarized how police harassment of media personnel and violation of the confidentiality of their sources has escalated in the Kashmir valley.

The Kashmir Press Club has constantly issued statements demanding the safety of journalists and criticizing the escalated state pressure on the media. According to the association, since August 2019, the police have booked at least five journalists on suspicion of criminal conspiracy and summoned five more journalists to police stations for questioning about their reporting.

Journalist Auqib Javeed wrote a chilling account in the online news portal Article 14 about his experience at the police station after he was summoned by cyber police in Srinagar in September last year.

“I was slapped twice by a policeman, intimidated over five hours, and verbally abused by an officer,” wrote Javeed. The authorities interrogated him about his report on how the police questioned Twitter users in Kashmir for their “anti-government” posts. The cyber police station in Srinagar denied that he was beaten and intimidated.

Countless people have lost their lives in the ongoing conflict in Kashmir. A boy photographs the grave of a slain armed rebel in Pulwama district, the site of encounters between the military and the militants. Photo: Aamir Ali Bhat

The troubling incident has increased Javeed’s anxiety levels. “I don’t feel free to do stories that I want to do,” he tells Asia Democracy Chronicles. “The state’s oppression of journalists has affected them mentally. But whatever pressure you are facing, in the end, you have to report the truth.”

Journalists in Kashmir say they are bearing the brunt of the authorities’ intense scrutiny and have chosen self-censorship as a strategy to survive as journalists. They feel that they are walking on a tightrope as they brave threats, harassment, and at times bullets to cover stories.

“It seems like danger is always looming over our heads,” says Saqib Majeed, a freelance photojournalist. A police officer beat Majeed and Shafat Farooq, a video journalist with the BBC’s Urdu service when they were covering the clashes that broke out outside the grand mosque in Srinagar after Friday prayers on March 5, 2021.

Majeed says, “When the police chased us, I ran away. One officer grabbed my collar and slapped me twice on my back. Such incidents bound your mouth with an invisible tape.”

An undaunted journalist

Despite the widespread crackdown on the press in Kashmir, some independent local news outlets have managed to produce stories even under tough conditions. However, the state consistently targeted these organizations.

Over the past year, the police summoned Fahad Shah — a Kashmiri journalist and the founder and editor of the weekly news outlet The Kashmir Walla — four times and interrogated him about his reporting. In September 2020, on his way home from covering an assignment in the state of Punjab, the police detained Shah in the local police station in South Kashmir. There they grilled the journalist for five hours.

More recently, the police summoned Shah to a station in Srinagar on March 5 and questioned him over his media outlet’s video story of the clashes between the local youth and the Indian security forces. In the face of relentless harassment, the journalist remains undaunted.

March 2020. The ruling party’s abrupt revocation of Kashmir’s autonomous status stripped the region’s residents of their political rights. The crisis led these women to protest in the streets of London, England.

Shah says the authorities have targeted his organization because they have been reporting what is happening on the ground in Kashmir since August 2019. “The more they put pressure on us, the stronger we become,” he says. “We always do factual reporting and will continue to do so.”

Muzzling netizens

Alongside the journalists, social media users in Kashmir have been summoned by the police, questioned, and threatened for criticizing government policies in the region.

In 2020, the cyber police summoned Adil* and questioned the netizen over his social media posts. “They asked me why I tweet about the Kashmir conflict and question the Indian state policies,” he says. “It was a nightmare.” Traumatized by the incident, he deleted all his social media accounts.

Adil is not alone. In August 2020, the local human rights group Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society released a report that documented 200 cases of social media and virtual private network users who were summoned to the police stations under various laws. According to the report, “Press freedoms and the right to freedom of speech, expression, and social participation suffered from the direct impact and chilling effects of online surveillance, profiling, and criminal sanctions.”

Tahir Ashraf Bhatti is in charge of the cyber police in Srinagar. He refuted that citizens were being summoned or tortured for expressing their political views online. In September 2020, he told Article 14, “We are living in a democratic country, and we have every right to criticize any government’s decision. That is how democracy works.”

I4C rollout

The reality, though, is different. In what is seen as an effort to muzzle social media users, the police in Kashmir issued a circular in February 2021 which asked citizens to register as cybercrime volunteers. The volunteers will check posts that go against the sovereignty of the nation, promote child and female abuse, and attempt to disturb law and order. The project is known as the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C). It is an initiative of the Union Ministry and was first started in Kashmir.

The administration rolled out I4C in Kashmir when it restored high-speed internet after an 18-month suspension. India placed Kashmir under communication blackout in August 2019 after stripping the disputed Muslim-majority region of its semi-autonomy. Under I4C, citizens were asked to register in one of three categories: identifying unlawful activity; promoting awareness to vulnerable groups; and working as an expert in more specialized areas such as malware analysis.

The central government on its website cites I4C’s objective as bringing “together academia, industry, public and government in prevention, detection, investigation, and prosecution of cybercrimes.”

However, critics say that I4C is an attempt to suppress freedom of speech. The definition of some of the points highlighted in the new project can be used to censor the media outlets and individual voices in Kashmir. “In the guise of protecting citizens from rising cybercrimes, the administration in Kashmir wants to tighten its grip on government critics,” says a research scholar who requested anonymity.

In March 2021, government employees in Kashmir were asked to submit the details of their social media accounts for police verification. A circular issued by a top administration department ordered all the administrative secretaries, division commissioners, and heads of various departments to get security clearance of unverified government employees from the criminal investigation department of the Kashmir police. Along with details such as name, date of birth, and address, the heads of government departments have been asked to provide details of “social media accounts (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, etc.)” of employees whose verification has not been carried out.

The order has led young people who are looking for a government job and are preparing for upcoming government examinations to worry whether their social media accounts would jeopardize their prospects. One young man who has recently been selected for a government job says, “I had thoroughly gone through my social media accounts and deleted some posts that I thought could land me in trouble. I ended up deleting all my social media accounts.” ●

* In the interest of safety, these interviewees’ names are concealed.

Aamir Ali Bhat is a journalist in Indian-administered Kashmir. He writes about human rights violations, politics, and the environment.