Not many people may have been surprised when UNICEF released a report early last month saying today’s global health crisis has put the world’s most vulnerable girls at increased risk of child marriage.

As many as 10 million additional child marriages may occur before the end of the decade, estimates UNICEF. The pandemic-induced school closures, economic stress, job losses, and parental deaths may drive many families to marry off their underage daughters.

In India, this regressive practice continues because it is socially acceptable — and even considered desirable — by traditional communities, say child rights activists. Even before the pandemic, one in three of the world’s child marriages took place in India; 102 million of its 223 million underage brides were married before their fifteenth birthday.

Despite the Prevention of Child Marriage Act of 2006, Indian child rights activists say that the regressive practice continues in the country because it is socially acceptable — and even considered desirable — by traditional communities. Folk songs and popular culture glorifying the beauty of 16-year-old girl brides across rural India attest to the fact that child marriage is considered normal.

In Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, located in northern and central India, families sometimes marry off baby girls to counter the ritual pollution that falls on a household following the death of an elder or a patriarch. The practice of “sibling exchange,” where a pair of siblings is married to another pair of siblings, is also common.

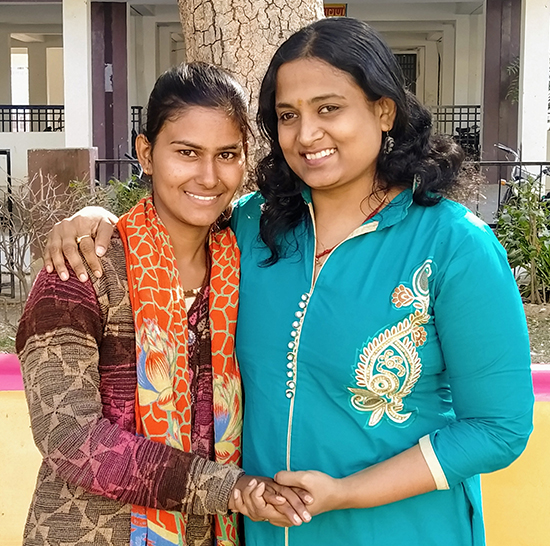

Dr. Kriti Bharti (left), founder of Saarthi Trust, played a key role in the first-ever annulment of a child marriage in India in 2012. She helped Lakshmi Sargara regain her freedom. (Photo: Saarthi Trust)

Child brides can stay with their parents till puberty, at which time their in-laws and the all-powerful caste elders insist that they be sent to their marital homes. Sometimes, poor parents save on wedding costs by simply marrying off the younger daughter/s when an elder sister gets married.

In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and many other states, some believe that a girl’s first menstrual period brings bad luck to her father. Girls are married off as soon as they reach puberty. Under Muslim personal law — which deals with marriage and divorce — child marriages are permitted with consent from the girl’s guardian.

“Economic distress, uncertainty, and lowered policing during the lockdown have led to countless such child marriages going unchecked in India,” says Dr. Kriti Bharti, founder of Saarthi Trust. The Jodhpur-based organization founded in 2011 is the first one to annul a child marriage in India in 2012. Since then, it has helped annul 41 child marriages and prevented 1,400 more.

A nationwide lockdown was enforced in India in late March last year and was eased two months later. Rumors of another lockdown are rife amid a surge in COVID-19 cases. Such a situation could trigger another spike in child marriages.

Across India, an estimated 5,584 child marriages were stopped during the first lockdown. However, it is hard to tell how many more have gone unreported.

Skewed sex ratio

Dr. Rolee Singh, program director of Varanasi-based Dr. Shambhunath Singh Research Foundation, notes the huge influx of young men returning to the villages of Uttar Pradesh during the pandemic. Singh has also seen how more girls than boys have dropped out of school in Uttar Pradesh during the pandemic.

“Jobs have been lost, family sizes have increased, but the resources remain the same. Who’ll bear the brunt but the family’s weakest link?” she says. More girls are being married off post-haste so that “their parents have one less mouth to feed — while their in-laws gain one more pair of hands!”

There is a growing suspicion that the increase in the incidence of child marriage in 2020 was partly due to a demographic shift caused by the unparalleled reverse migration that India experienced during the lockdown. According to government estimates, over 30,000 workers returned to their villages in Uttar Pradesh during the lockdown.

Saarthi Trust holds “orientation camps on child marriage” in schools to inform adolescents about how the regressive practice harms both boys and girls. (Photo: Saarthi Trust)

With its already skewed sex ratio — 902 females for every 1,000 males, according to the 2011 census — the pool of marriageable females has grown younger. Before the pandemic, Singh typically encountered girls aged 15 or 16 at the altar. Now she’s seeing girls as young as 12.

The foundation has been counseling families at risk: those who have more than three daughters, are poor, and are headed by illiterate parents. Unfortunately, local marriage brokers also prey on the insecurities of such families and convince them to get their underage daughters married.

Singh also suspects that cases of child sex trafficking may have increased during the pandemic. She says, “We’ve heard of cases of men from Rajasthan, Haryana, and other states marrying underage girls from Uttar Pradesh and giving their families US$800 to US$1,300 as ‘financial assistance.’” Singh says that the small organization can hardly cope with the three to four distress calls that they have received from girls every day since the lockdown.

A lost year

Jodhpur is known as India’s child marriage annulment capital. In the city, Bharti chafes against the slow pace of the judiciary. The National Judicial Data Grid shows 26,642 marriage petitions, including divorces, are pending in Rajasthan’s district courts right now. Among these cases are underage brides that she is helping with legal aid and counseling.

“I should have gained my freedom last year,” rues Pooja Jandu, a 19-year-old college student. She was married against her wishes at age 12 during her elder sister’s wedding. Her unwilling parents were pressured by the caste elders who sanctioned the marriage. However, when Pooja turned 18 and her husband insisted that she be brought to him, her family went against the wishes of the elders. They applied to have her marriage annulled in 2019.

The lockdown has delayed the proceedings, though. “I fear the elders might pressure my parents into taking the case back,” says Pooja. The caste elders disapprove of annulment. They have been known to impose fines and even cast out girls like Pooja and her family who want a way out.

Rekha Bishnoi, 20, who filed for an annulment mere weeks before the lockdown, tells a similar story. “Our first court hearing was to be on April 4, 2020,” she says. “Imagine my frustration!”

The two young women say that the uncertainty of the situation has caused untold stress to their families. Sanju Jangid, 19, is in the final year of her undergraduate course. She is another woman who has filed for an annulment. Sanju blames the strain of waiting for her father’s death in April 2020.

“My husband’s family was incensed when we applied for an annulment,” says Sanju. She was married off at the age of three along with her five elder sisters. “They threatened us with dire consequences if we continued with the case.” When the lockdown stalled her case, the pressure mounted. Sanju’s father had a fatal heart attack.

Today, Pooja, Rekha, and Sanju are all waiting for justice and their freedom. Bharti says they are still lucky. During the lockdown, she learned of more than 50 girls who turned twenty in 2020 before they were able to file their applications for annulment.

“According to the law, girls can only apply for annulment on the grounds of child marriage within two years of reaching legal age, which is 18 in India,” says Bharti. “Now they will have to file for divorce.”

A failure of the law

Child rights advocates believe that the Prevention of Child Marriage Act of 2006 has failed to protect underage brides. While the Act deems child marriage an illegal act, the marriage itself is legally valid.

This means that underage brides — and a few grooms, too — should seek an annulment within two years of reaching legal age. Older appellants are forced to seek a divorce, a lengthy legal process with negative social connotations. Moreover, child marriage cases are dealt with in regular family court, without an appropriate rule framework or a mandated timeframe in which they must be resolved. Annulments without mutual consent endlessly drag on as the onus of proving the marriage and age of the parties concerned falls on the appellant.

“Marriages that have occurred quietly in the shadow of the lockdown are going to be especially hard to prove,” says Bharti. “And the present circumstances have prolonged many annulments without mutual consent, during which time the girl is in constant danger of being forcibly dragged to her marital home.”

The implementation of the law is fraught with loopholes, too. “In Uttar Pradesh, when the administration gets wind of a child marriage, they get the parents to sign an affidavit swearing that they would not get their children married,” says Singh. “Parents sign it and quietly go ahead with the marriage anyway.” This happens in Rajasthan, too.

In 2017, the Bangalore-based Child Rights Trust successfully argued for making child marriage void ab initio in Karnataka on the argument that it was impractical to expect a minor to come forward and contest his/her marriage. Today, Karnataka has become the first Indian state to declare all child marriages void at the outset.

A solution

However, activists fear that the ruling in Karnataka could further disempower young girls. If the law made child marriage void from the beginning while not putting an end to the practice itself, child brides would not even have a legal document to prove their marriage and demand reparations or an annulment. “Imagine the plight of victims who have been forcibly sent to their husband’s homes, lived there for a while, and possibly even had children — only to learn that their marriages have no legal standing!” says Bharti.

Dr. Bharti calls Sanju Jangid (left), who was married off at the age of three, one of the lucky ones. The 19-year-old filed her application for annulment before the lockdown. (Photo: Saarthi Trust)

One solution is to identify, as the Varanasi-based foundation does, families at risk and to empower them socially and financially. Singh and her cohort of field workers help such families gain access to government entitlements like scholarships as well as livelihood opportunities. “We believe that financially secure parents will be more likely to protect their underage daughters,” says Singh.

At the same time, Indian law simply should make it easier for child marriage survivors to get the justice that they seek. “We need for the police, judiciary, government hospitals, and schools to be sensitized to this problem,” Bharti says. Such agencies are legally bound to report cases of child marriage. In practice, though, this rarely happens. Also, if marriages were compulsorily registered under the Prevention of Child Marriage Act in every state, it would be harder for the marriages of minors to take place.

Meanwhile, Pooja, Rekha, and Sanju continue to wait for justice and hope the travails of 2020 will soon be behind them. “I can’t wait for this unbearable tension to end and to finally become free,” says Sanju. ●

Geetanjali Krishna is a contributing editor with Business Standard and is the co-founder of The India Story Agency, which specializes in telling human interest, environmental, and social affairs stories and case studies from South Asia to the world. Her recent by-lines can be found in Times, BBC, Footprint magazine, and Business Standard.