By Shao-hua Liu; translated by Liang-Wei Huang

For decades now, my research has been concerned with the prevention and control of infectious diseases in post-1949 China or after the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China.

I have long sighed with regret that no matter how much scholars like myself have conducted research and uncovered the lessons that we must learn from history, whenever there is a major disease outbreak in China, the story of untold suffering always repeats itself.

The studies written by longtime researchers like I, who care deeply about the suffering of the Chinese people, are still suppressed. How then can a society that refuses to learn the lessons of history act for the benefit of future generations to come?

It was all-too-familiar to watch the unfolding of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan in December 2019. Since the leprosy prevention program in post-1949 China until the 2003 SARS outbreak and HIV epidemic, the responses of the central and local governments and of the general public have followed a familiar pattern: categorical denial, the outbreak of the epidemic, forced confessions, mass and forced quarantine; stigmatization spreading faster than the disease itself; the lack of a cohesive plan for citizens’ livelihood; medical personnel pushed to the frontline without any backup policies; and public outrage.

Widespread stigma

And then what? The coronavirus epidemic in Wuhan will eventually be quelled with violent yet largely effective preventive quarantine measures. After it has subsided, everything will go back to their daily routine of issuing categorical denials, forgetting history, and banning any faithful record of the event. The only thing that may remain is the prevalent stigma against the people living in the disease-stricken area. As with Henan province and AIDS or with Liangshan and heroin use, Wuhan will become synonymous with the coronavirus.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, the responses of China’s central and local governments have followed a familiar pattern that starts with a categorical denial.

Yet, as for how the people got in and out of the abyss of misery, no one ever asked. Those living outside of the infected areas don’t care about these issues. As for the people carrying the stigma of disease, they may be more focused on denial. Few are willing to look into the root cause of the stigma or into the indifference and ineptitude of those in power.

The root cause

The absurd measures taken to control the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan triggered outrage at home and abroad. People are aware that the Chinese central and local governments are to be blamed. Some say the main problem is authoritarian control, while others say the problem lies in the persistent bureaucratic corruption at local levels. These are symptoms of a deeper problem.

What I set out to do here is to explore the root cause behind the failure of the interventions meant to alleviate disease outbreaks since 1949. What’s behind the recurring history of chaotic disease prevention and control efforts in China?

The most crucial factor is a toxic mix of nationalism and mianzi or the notion of “saving face.” In political parlance, it is the question of Chinese “subjectivity” in the face of “imperial” or “foreign” encroachment.

Researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine estimate that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was “likely circulating undetected for at most two months before the first human cases of COVID-19 were described in Wuhan, China in late-December 2019,” reports Science Daily.

This is the key reason why I used the post-imperial ideology to analyze leprosy prevention in post-1949 China in my book, Leprosy Doctors in China’s Post-imperial Experimentation: Metaphors of a Disease and Its Control (hereafter Leprosy Doctors in China’s Post-imperial Experimentation). Everything is driven by China’s anti-imperialist and anti-American sentiment — whether the Chinese succeed or fail at combating the disease and whether they censor the bad news or selectively glorify their accomplishments. Individuals play along voluntarily or involuntarily to help the country save face. They bury scandals, push back at outside criticism, and sacrifice their individualism to protect the collective image.

Naturally, face, subjectivity, or ideology is led by the central authority that upholds Chinese subjectivity, and it is supported by the masses who are equally patriotic and respectful of their country. Under the banner of national consciousness, Chinese patriotism can be heartbreakingly naïve.

Indeed, it is commonplace that every state lays emphasis on its subjectivity. However, if the bitter lessons from history are repeatedly discredited and erased in favor of a deep sense of nationalism, our generation and the generations to come will inevitably face recurring challenges arising from disease outbreaks.

The public might not learn lessons from history, whereas a virus inexorably mutates in response to changes in the environment. Which is tougher, human beings or a virus?

A deaf ear

Taking the two in-depth studies I did on AIDS and leprosy, for example, I can point out common problems of “subjectivity” taking precedence over everything else in epidemic control. The ideology-driven subjectivity of face takes precedence over sound scientific principles of disease prevention; it forbids any critical discussion and any factual recordkeeping that may disgrace the state. The loss of historicity makes it impossible to effectively address future problems.

In the conclusion of my book, Passage to Manhood: Youth Migration, Heroin, and AIDS in Southwest China, I mentioned that prior to 2000, the Chinese authorities denied any severity of AIDS outbreak within the country. Not until the New York Times ran a devastating feature story about an AIDS outbreak caused by unsafe blood collection practices in Henan Province did international agencies begin to pressure the Chinese government to acknowledge the colossal crisis it faced with AIDS and to accept international assistance in curbing the epidemic. Since then, the Chinese government became significantly more open in tackling the problem in collaboration with international agencies.

However, at the grassroots level, saving face still takes precedence over everything else. Local governments choose to report only the good news and not the bad news. My book Passage to Manhood demonstrates exactly the inconsistency between the central and local government. The book has attracted a lot of attention since its publication in China.

Did the book make any difference? This is a question I’m frequently asked by Chinese readers. I always have a hard time answering it. How I hope that my research can be of assistance to those who have been suffering! Sadly, the management of disease outbreaks remains unchanged. In addition, my research monographs are no longer available to readers who are desperate to understand the history of disease prevention and control. Again, the lessons from history are suppressed in the state’s interest to save face.

The more I study China’s infectious disease prevention and control, the more I realize that in order to come to terms with the current pandemic, we have to fully grasp what had happened in the past and to understand the key factors that sowed the seeds for today’s chaotic situation.

A vicious cycle

Right before the Lunar New Year, many news stories and images of patients infected with COVID-19 being placed inside isolation boxes and taken away to quarantine appeared on my WeChat feed. They reminded me of a story I wrote in my book Leprosy Doctors in China’s Post-imperial Experimentation:

“In Xinjiang …, the locals found that a Shanghai guy grew Mafeng [Mycobacterium leprea] so they chartered a cart of a train to transport him back to Shanghai…. There, the disease prevention workforce sprayed disinfectant along the road the patient just walked through. The farther the patient traveled, the more the workforce sprayed disinfectant out of fear.”

Fear, stigmatization, excessive disease control and prevention measures, and the helplessness of medical staff have been prevalent in China for a long time. If nothing changes, the people will undoubtedly pay the high costs of mismanaged disease prevention and control. By refusing to openly acknowledge its ill-advised disease prevention measures and reflect on its own history, China has created a vicious cycle of denial, stigma, fear, ineptitude, and abysmal misery.

Following is what I wrote in the preface of Leprosy Doctors in China’s Post-imperial Experimentation:

“What does the story of Chinese disease prevention mean to the world? It is not just an issue in medical and public health history. [Examined] through the lens of the controversial Chinese post-imperial experimentation, it is more of a political and social history question.”

A heavy burden

Writing Leprosy Doctors in China’s Post-imperial Experimentation has brought me a heavy burden. I feel nothing but deep pain when I see how history has repeated itself since 1949. In the conclusion of the above book, I employed differing versions of histories (the Rashomon of history) to contest the official account of history and the silenced history:

“Against the backdrop of globalization, we see [how] numerous attempts and actions taken by Chinese government failed to address the disease control goals. Luckily, an open and free society that values transparency and has respect for [the] individual is self-critical of its own wrongdoings. Being able to reflectively [look] inward, a society can adjust itself in the face of recurring epidemics.

To date, however, stories of countless lives, including patients and doctors, ruptured by China’s ill-advised leprosy control policy have remained little-known to the public. Under such circumstances, the society still has a long way to go until it can take the initiative to heal wounds.”

A difficult art

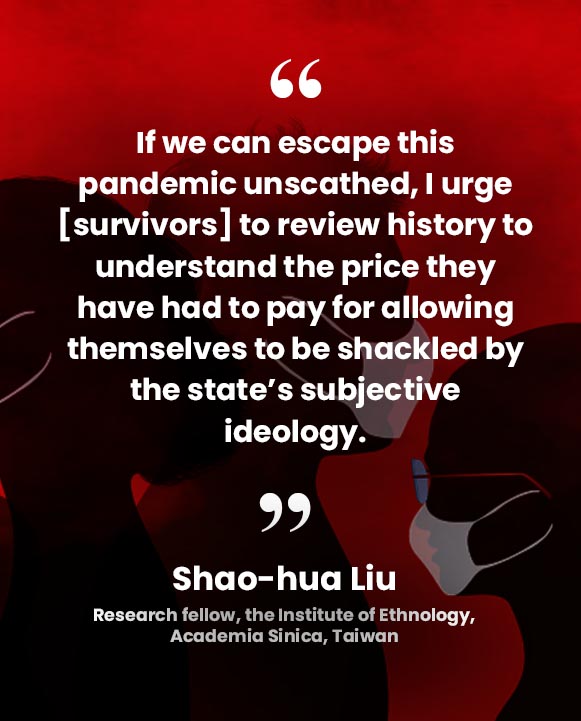

What I write here now is for the survivors in China to read. If we can escape this pandemic unscathed, I urge them to review history in order to understand the price they have had to pay for allowing themselves to be shackled by the state’s subjective ideology.

The citizens’ habitual pretending to be ignorant of problematic governance in the interests of patriotism and saving face, pushing back at international criticism, and scapegoating those who reveal the truth for the sake of preserving the nation’s image is a denial of history and simply gripping the fig leaf of patriotic subjectivity. The next time a wave of disease arrives in China, the government would still be incapable of protecting the people and the country. ●

Shao-hua Liu is a research fellow at the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. Her research interests include medical anthropology, globalization, modernity, gender, and rural health and medicine in contemporary China. She is the author of the books: The Anthropology Living in My Eyes and Blood (Chunshan Chubanshe, 2019); Leprosy Doctors in China’s Post-Imperial Experimentation: Metaphors of a Disease and Its Control (Weicheng Chubanshe, 2018); and Passage to Manhood: Heroin, AIDS, and Youth Migration in Southwest China (Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University, 2010).

Liang-Wei Huang translated this article from Liu’s article that was posted online on January 29, 2020.